How a Wisconsin farm girl ended up running a luxury car company, part 1: The Lady of the Lake

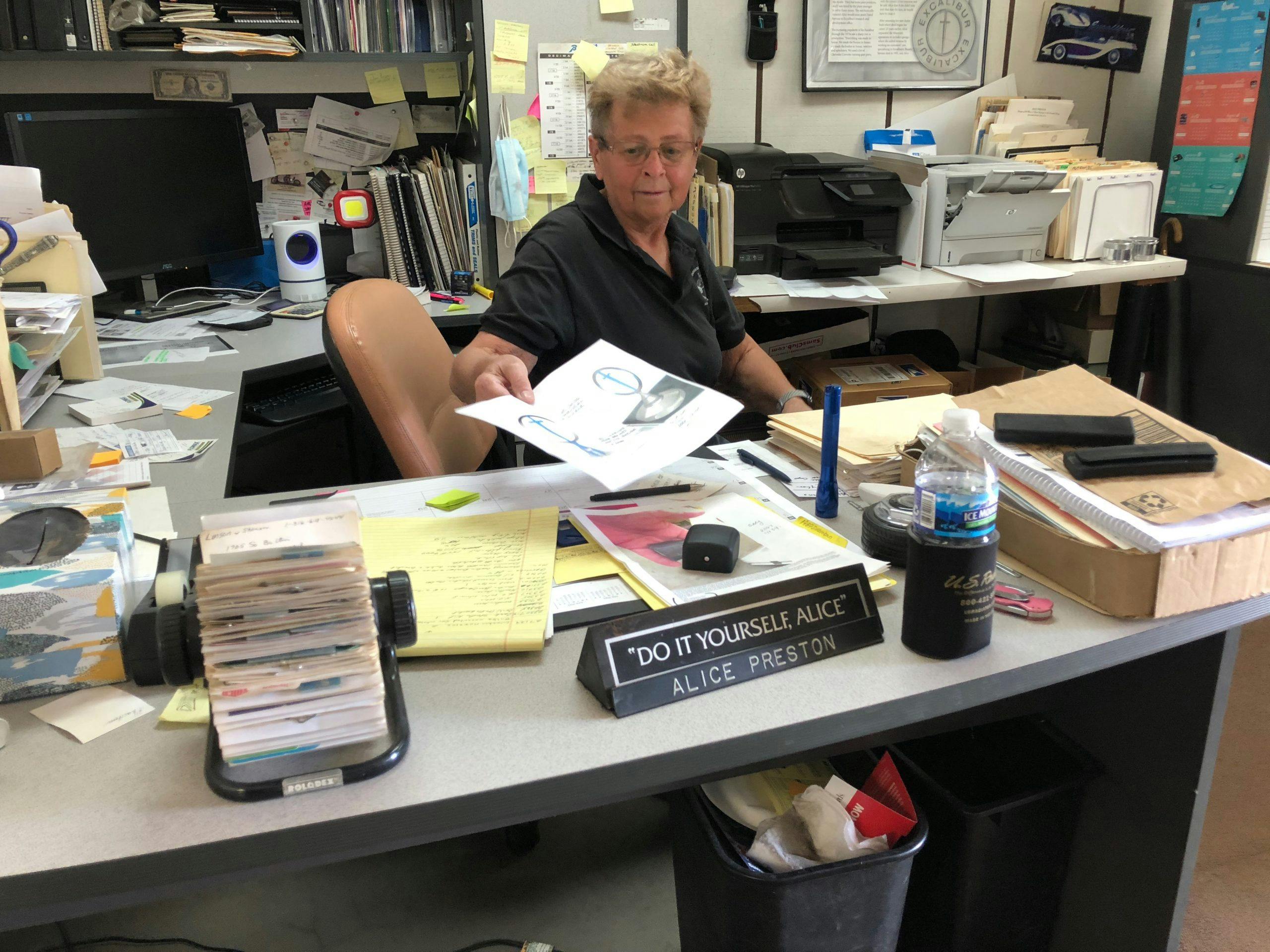

Alice Preston has done more in one life than most people could do in ten. She’s been a farmer, a racing mechanic, a tavern owner, a machinist, a factory manager, a home improvement contractor, a museum curator, and a classic car restorer. She’s worked alongside auto industry bigwigs, partied with celebrities, survived cancer, and been married twice—first to a man and, currently, to a woman. She also happens to be the current owner and boss of Excalibur Automobile Corporation, the company responsible for some of the greatest neoclassic cars ever built.

On a breezy summer afternoon, Alice shows me around the buildings at Camelot Classic Cars, her repair and restoration business dedicated to keeping remaining Excalibur vehicles on the road. Despite her diminutive size, she radiates an intense, no-nonsense energy. Having worked on these cars for over half a century, she knows Excaliburs inside and out.

Her connection to the cars goes back to before the company’s founding. It’s difficult to parse out whose story is more interesting, Alice’s or Excalibur’s. As it happens, the tales are deeply intertwined, and both start out near Milwaukee.

The legend begins

Alice learned how to fix things the hard way—by growing up on a farm. After dropping out of high school in ninth grade, Alice helped support her family by working at a movie theater and the local Enco service station. There, she did more than pump gas and wash windows. By the time she was a teenager, Alice had become a very capable mechanic.

“If you’re out on a tractor, and it breaks, you’d better know how to fix it, or you’re gonna be walking back!” she says with a laugh.

One day in early 1963, seventeen-year-old Alice had a chance encounter that changed her life.

“A guy came in with a ’47 Mercury woodie wagon with a bad battery, and needed a new battery. He was impressed that I knew what the car was … And he said, ‘Well, if you really want to work on some cool cars, we have an opening out at the Brooks Stevens Auto Museum. There’s a bunch of old cars there that haven’t run in years. There’s nobody to take care of them.’”

The man in the Mercury turned out to be Ronald Paetow, a colleague of industrial designer Brooks Stevens. At the time, Stevens was a leader in his field, with work that could be found in almost all spheres of American life. He’d helped create everything from home appliances and railroad cars to cardboard packaging and speedboats. By the early ’60s, some of his most notable designs included the Jeep Wagoneer, the Studebaker Gran Turismo Hawk, and the Oscar Mayer Wienermobile.

Profits from his design work helped fund a large collection of antique cars, which he displayed at the Brooks Stevens Auto Museum in Wisconsin. It just so happened the museum was looking for a mechanic when Ron met Alice.

“So I went out there and talked to [Ron], and he said, ‘I have the perfect job to test you to see if you know what you’re doing.’ It was an International Harvester … a big old green Travelall … and he wanted the tappets adjusted.

“You have to have the vehicle running, obviously. I had hair down to my butt, cowboy hat, jeans, and cowboy boots. And I’m sitting on the inside fender well, adjusting the tappets on this thing, and Mr. Stevens came in and Ron goes, ‘Oh, Mr. Stevens, I want you to meet the new mechanic for the museum!’

“And he goes, ‘Well if he’s going to work for us, he needs a haircut.’

“‘No, this is Alice Preston!”

“‘Oh! Call me Brooks.’

“I got the job, and we became great friends.”

***

At the time Alice began working at the museum, job opportunities for women who liked cars were scarce. Only 40 percent of U.S. women participated in the labor force (compared to almost 60 percent today). Few dreamed of becoming mechanics.

“When you’re young and in the ’50s and ’60s, you’re really brainwashed into, ‘You need to conform, you need to conform …’” Alice says. “You know, the girls in school treat you different because you do boy things.”

However, she soon felt right at home wrenching on the museum’s collection.

“Brooks was very good. If you knew what you were doing, he was good with it. And he taught me a lot.”

Soon after, the Studebaker Corporation contacted Stevens’ design firm to commission a concept car for the upcoming 1964 New York Auto Show. Stevens had designed a number of iconic vehicles and concept cars for the company over the years, and management hoped that a flashy, new show car would boost prospects for the financially ailing company and its aging lineup.

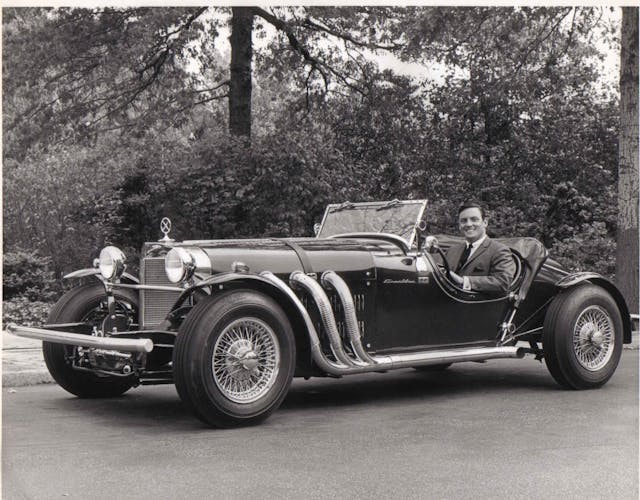

Working with his sons, Dave and Steve (William), in what was then Dave’s model shop, Brooks created an elaborate, vintage-styled open roadster with an upright grille, wire wheels, and long, flowing side pipes. Called the Studebaker SS, the concept clearly drew inspiration from the past.

“[Brooks] had a 1928 Mercedes-Benz that was owned by Al Jolson that I restored later,” Alice says, “and he loved that car. He made this car look like a smaller version of that Al Jolson Mercedes.”

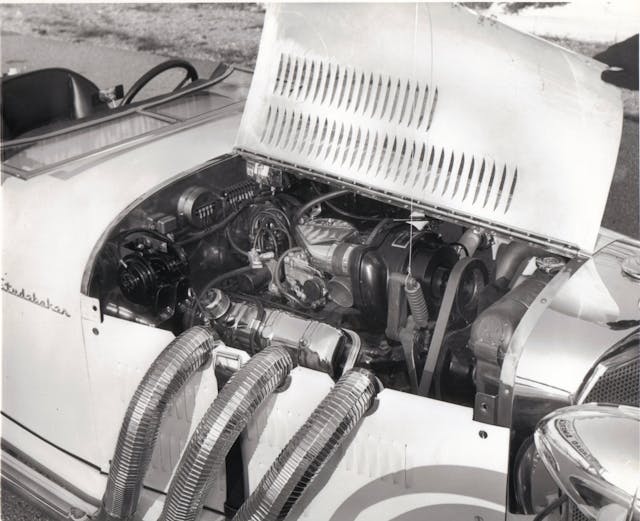

Built on a modified Studebaker Daytona convertible chassis, the two seater SS (often referred to as the “Mercebaker” by Brooks and his team) was designed to go fast, with an aluminum body and a supercharged Studebaker R3 V-8 from the recent Avanti sports car. Although technically an employee of the car museum and not of Brooks’ design firm, Alice couldn’t resist helping where she could.

“We built that car in six weeks!”

All their work almost went to waste. Studebaker management had apparently given Brooks carte blanche, but a vintage Mercedes look-alike was not what they were expecting.

“When they saw the Series I … they went, ‘Oh no.’” Alice remembers. “Because it’s a two seater with no doors. [Brooks] was looking to compete with some of the other two-seat things out there.”

The concept came at a colossally bad time. Studebaker already had one halo car, the Avanti, and management had just announced the planned closure of its main manufacturing plant in South Bend, Indiana. With severely reduced capacity in Canada, there was absolutely no chance that the company would produce a retro roadster. Even teasing such an idea at an auto show made no sense.

With all the work that had gone into the Mercebaker, the Stevens family refused to let it die. Brooks pulled some strings to get the car into the auto show as a standalone exhibit—next to a hot dog stand, of all things—and it became a smash hit.

“Well, crap, that thing was the hit of the show!” Alice says. “People were throwing money at them, saying ‘I want a car like this!’”

If Studebaker didn’t want it, the brothers were going to find a way to produce it. The SS traveled across the country, drumming up excitement and rousing potential customers. Steve went to Brooks and convinced his father to lend him and David ten thousand dollars to start a factory to build the cars. Combined with some money from the bank and the deposits for preorders, the Stevens brothers joined the long list of intrepid Americans brave enough to start their own car companies.

As for Studebaker?

“They just said, ‘Well, good luck with it … If you’d like to buy the chassis, have at it.’”

A call to adventure

Since the company in South Bend was mostly out of the picture, the brothers decide to rebrand the car. Brooks Stevens had used the name “Excalibur” on various concepts and vehicles dating back to the race cars he built in the early ’50s, which were based on Kaiser’s Henry J. (His grandson Anthony still owns an original Excalibur J.) The legendary sword of King Arthur seemed like the perfect name for a large, lavish, vintage roadster.

“A lot of [cars] had sword names,” said Alice, “And this was the best car; he wanted the best sword. Nobody had used it. Excalibur.”

The Studbaker SS became the Excalibur Series I, and the curvy “S” hood ornament became an “X” in a circle.

“Well, Mercedes had a hemorrhage and said people couldn’t tell the difference between the X and a three-pointed star,” Alice says, rolling her eyes. “So instead of the X, we just put the sword in there.”

Studebaker’s exit from the project proved to be fortuitous, even though the Indiana company would soon cease production of its own engines. Steve and Dave knew manufacturing powertrains in-house was out of the question, and they already had a lead on where to look next.

“There was a dealer who said, if you make these with Chevrolet running gear instead of Studebaker, I’ll take all you can build and sell them,” Alice said. “So we started working with Chevrolet.”

The Studebaker Daytona chassis would remain, but the drivetrain would be a Chevrolet 327-cubic-inch V-8, coupled to a three-speed automatic transmission.

Deliveries started in 1965.

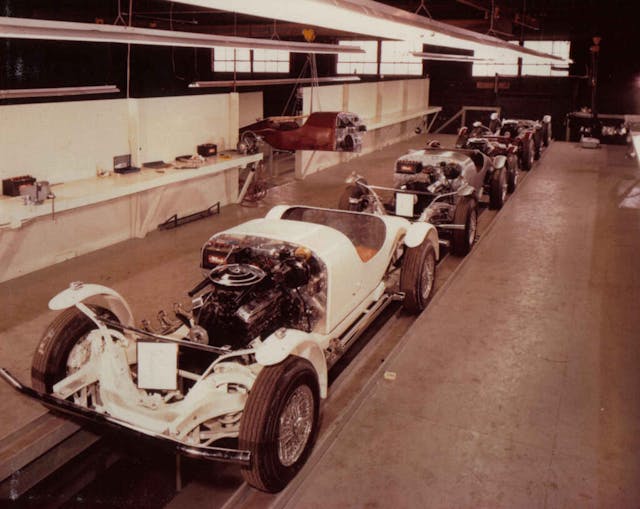

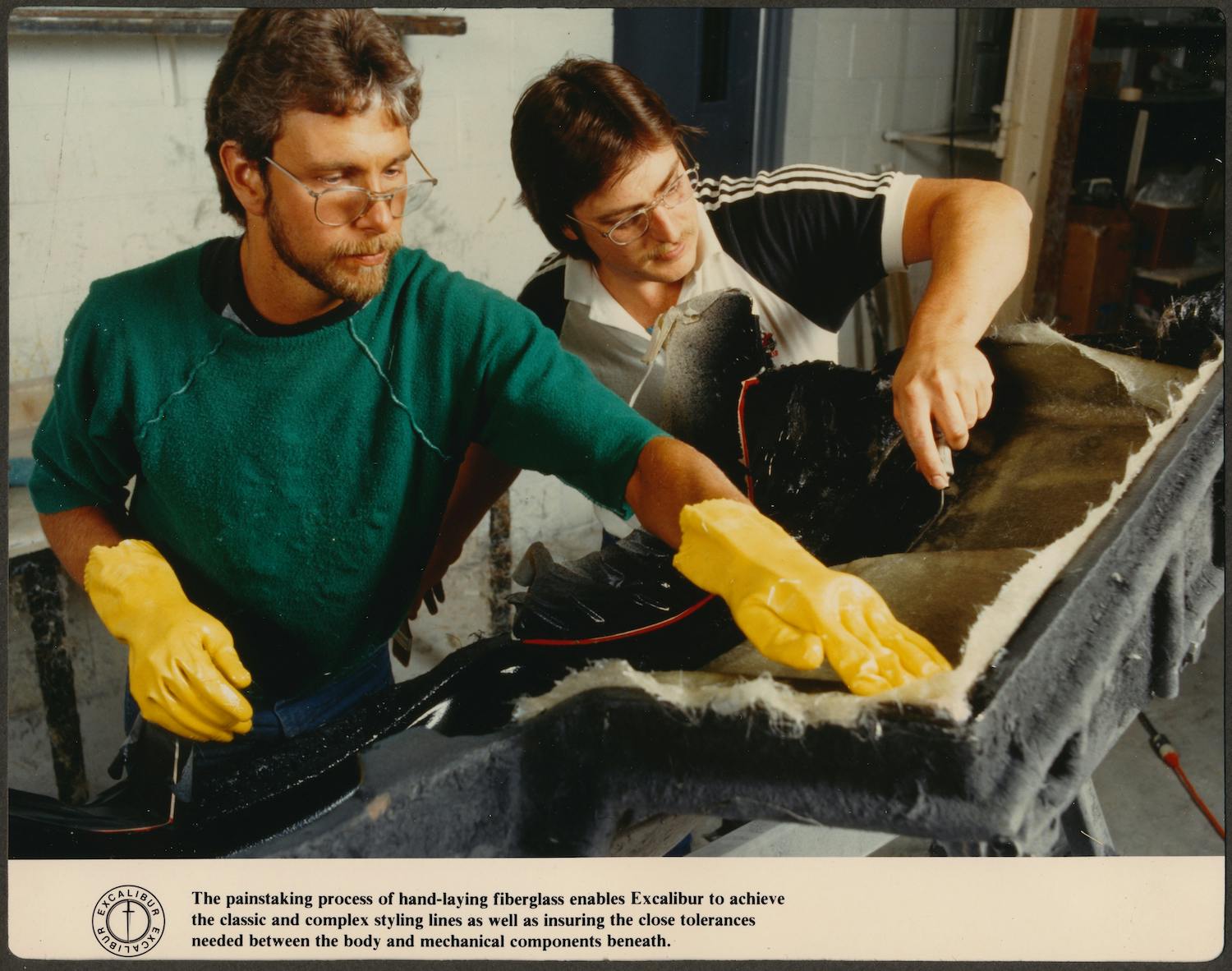

“The first couple were made out of aluminum, and the prototype was aluminum,” Alice says. “Once we knew we were going to be making more, it would just take too long. That’s when fiberglass was the new, big, up-and-coming thing … So Dave said, ‘Let’s try pulling a mold off of one of these and see what happens.’

“It was much easier. Fiberglass likes any kind of shape you want to give it; it loves curves.”

Their goal was to create what Brooks called “a modern classic,” a vehicle that combined classical styling with modern performance, amenities, and reliability. As the owner of many antique cars, Brooks understood both the timeless appeal of their style and the frustration of their never-ending need for repairs. (That’s why he had hired Alice at the museum, after all.) By using modern, off-the-shelf parts, Excaliburs would hopefully be more reliable, but they certainly wouldn’t be cheap.

“A Series I was $6000,” Alice says, chuckling. “In 1965, a brand-new Cadillac, fully loaded, was $3200, and it had amenities! This had nothing, not even doors!”

Still, there was no other vehicle in the world quite like an Excalibur, and wealthy customers loved them.

An epic quest

Alice had plenty to keep her busy. By 1969, she’d married Ron. The couple opened a machine shop and bought a local restaurant. “I’m doing machine shop [work], I’m tending bar at night, and I’m working on restoring that whole building,” she said. Her work at the museum transitioned to part time. Finally, she had to let it go.

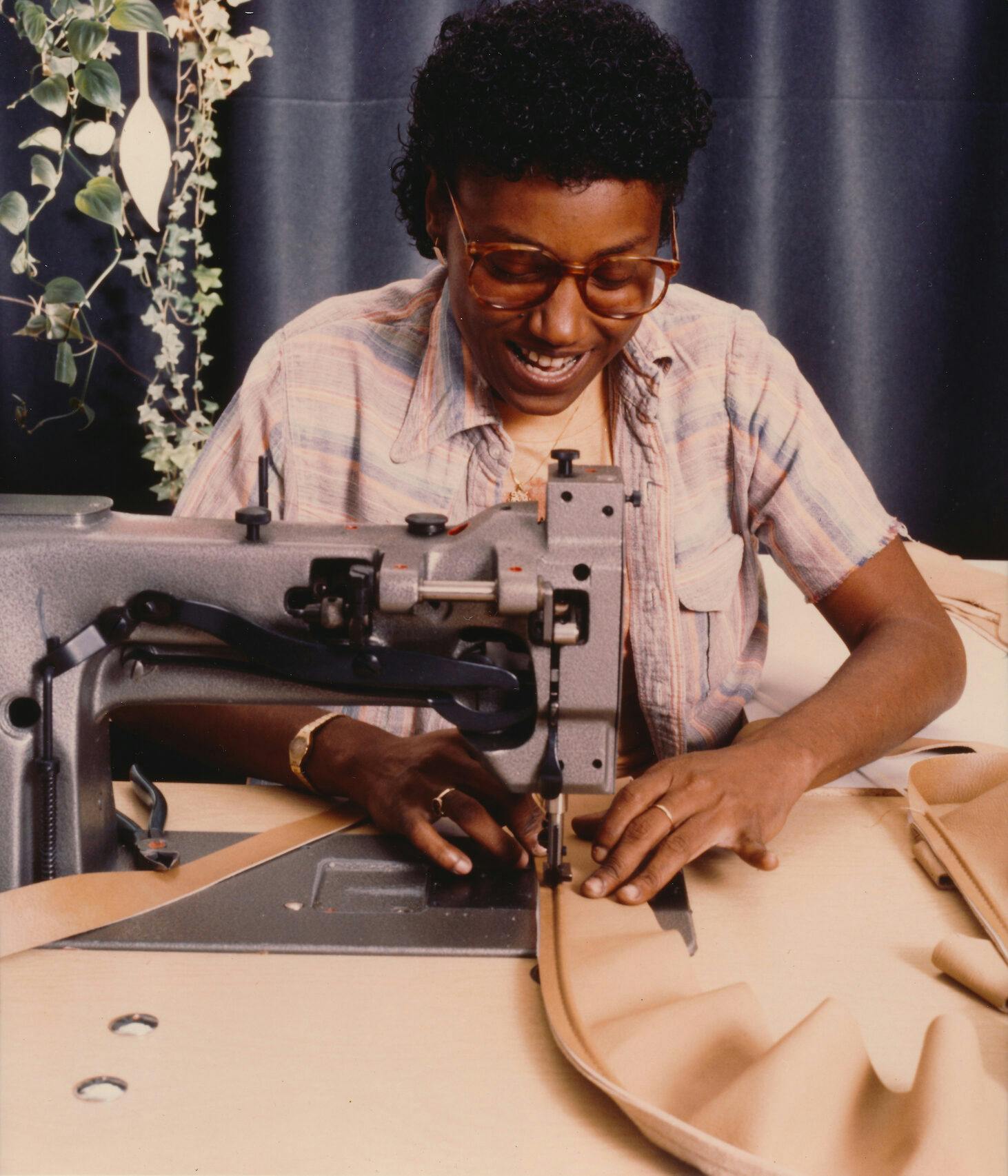

She and Ron continued to machine parts as needed for SS Automobiles (later renamed Excalibur Automobile Corporation), which was finally off the ground and busy producing low-volume, made to order cars. The catalog expanded from the original, two-seat roadster to include a four-seat phaeton, still with no doors. By the end of 1969, they’d managed to sell 349 units.

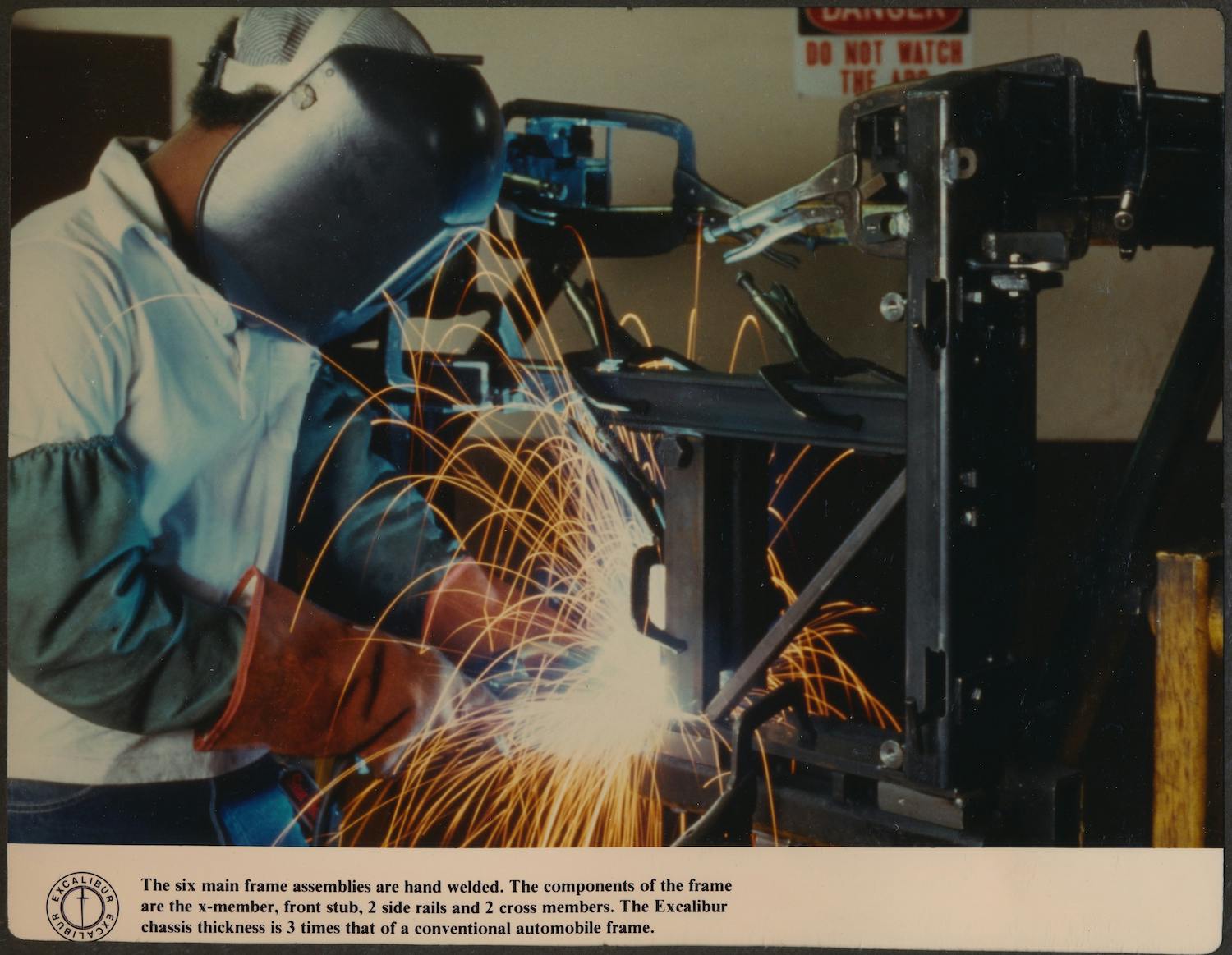

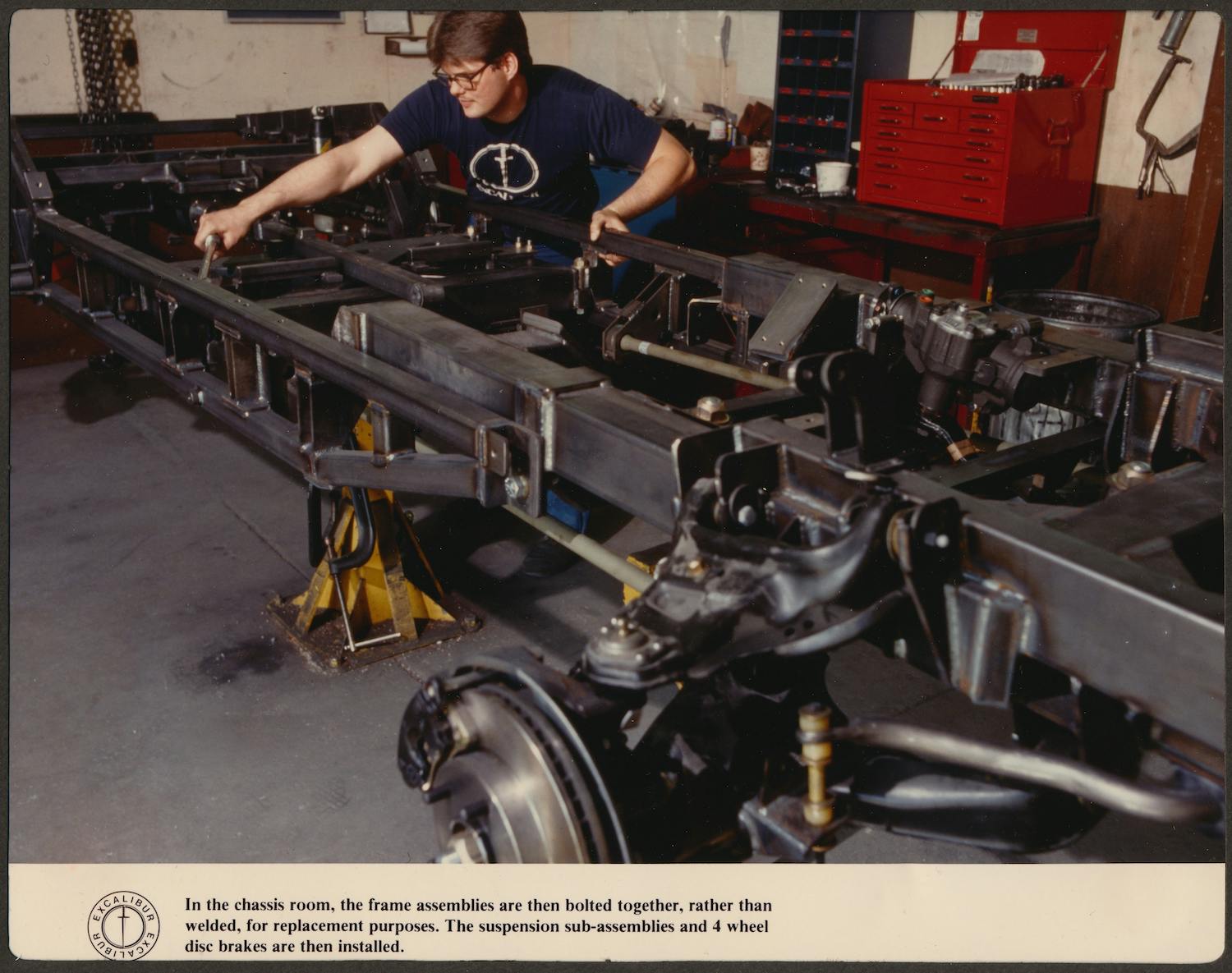

In 1970, the brothers launched a new Series II models, boasting a bigger, 350-cubic-inch engine from Chevrolet, a unique ladder chassis (no more Studebaker parts), an optional four-speed manual gearbox, and real, working doors. Despite their elegant, old-school appearance, the cars were fast. Pre-smog-era cars could do 0-to-60-mph in around 7 seconds, making them competitive with all but the quickest muscle cars. 1972 would see the addition of a 454-cubic-inch big-block engine, with even more power.

However, production struggled as SS Automobiles adapted to the new design. The cars were essentially all hand-built, and without the facilities of a major automaker, Dave and Steve faced a lot of challenges. Meanwhile, Alice’s personal life had become significantly more complicated. She’d separated from her husband and their joint business ventures, taking over the machine shop and starting a home renovation business.

“It’s not a good thing when you own a tavern and there’s too many other people around,” she says. “Too much hanky-panky. And I’m like, ‘Why’d you wanna get married, then?’” Still, the two remained friends.

Around the same time, Dave and Steve hired her at Excalibur. “They had paint issues in the early ’70s,” she explained. “So then I went there full-time to solve those issues.”

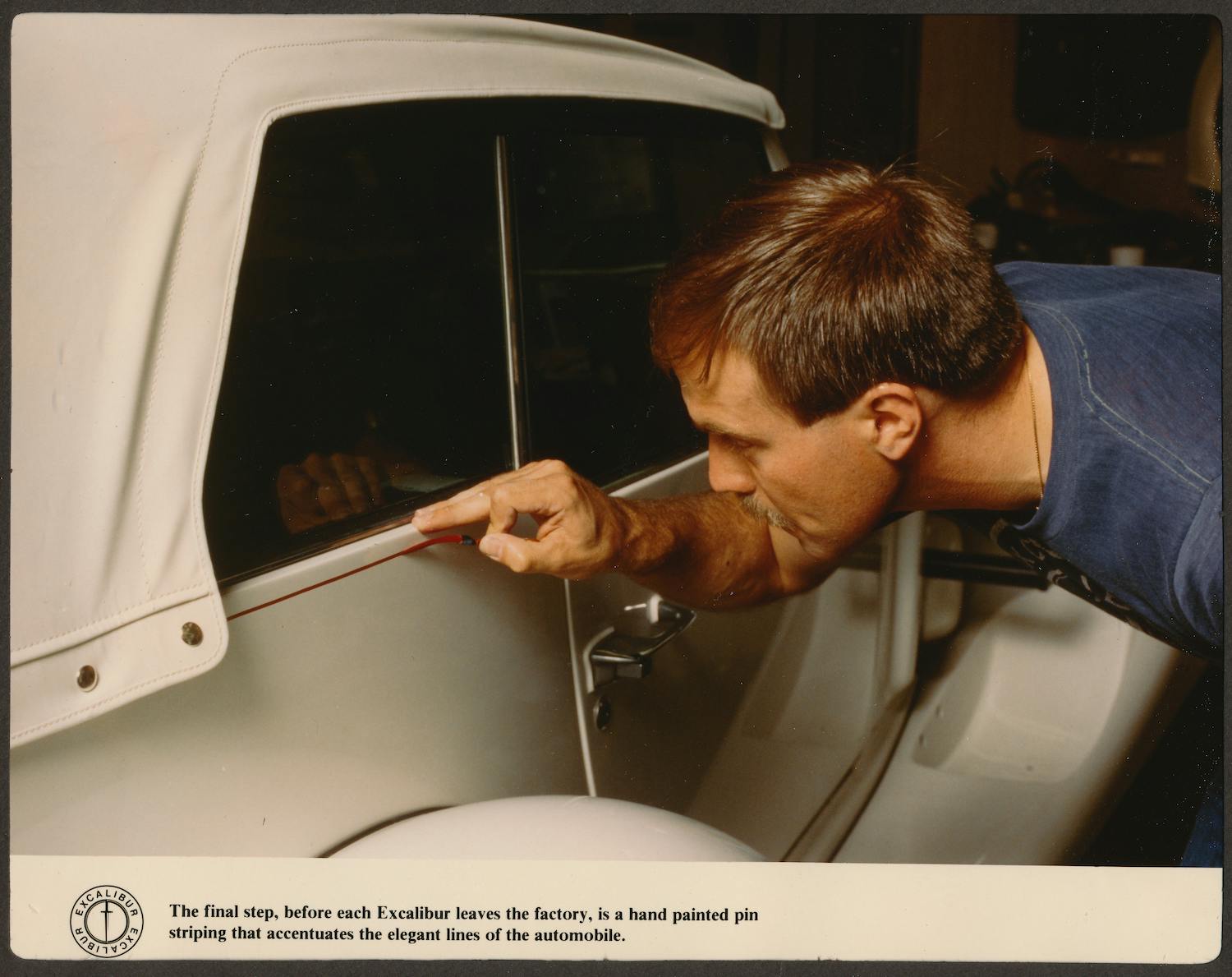

After several years of ownership, Excalibur owners began to complain that their vehicles’ paint was cracking and shrinking, especially after prolonged sun exposure. Such problems would be embarrassing for any car company, but as Excalibur prices had now risen to over $12,000, customers expected the paint quality to be impeccable.

“There was alligator cracking and stuff after the cars were painted, because fiberglass tends to move,” Alice explains. “And in my estimation, it was because it was green fiberglass, so all the solvents aren’t out of the fiberglass—and then you’re putting two or three coats of primer on it. Then we’re laying on three-four coats of paint and then buffing it. A couple years later, it’s cracking wherever the sun can hit it. The solvents started shrinking the coatings that were on top of it.”

The solvents simply needed to be baked out of everything, Alice decided. She and the team made jigs and set up an oven in the company’s fiberglass department. “You dry it out, roll it upstairs on the same jig, get the primer and stuff on it … and then bake it again. That solved the problem!”

Each body was now baked three times before it left the factory, and the complaints of cracking paint stopped.

With years of experience as a mechanic, an antique car restorer, and a machinist, Alice became the unofficial jack-of-all trades at Excalibur. Eventually her role grew until she was managing five different departments within the company. At the same time, she was moonlighting as the head mechanic for Brooks Stevens’ racing team. Despite the workload, she loved it.

“Like Dave said, there was no real title. I was a problem solver. I still am. If there’s a problem, let’s fix it.”

The kingdom grows

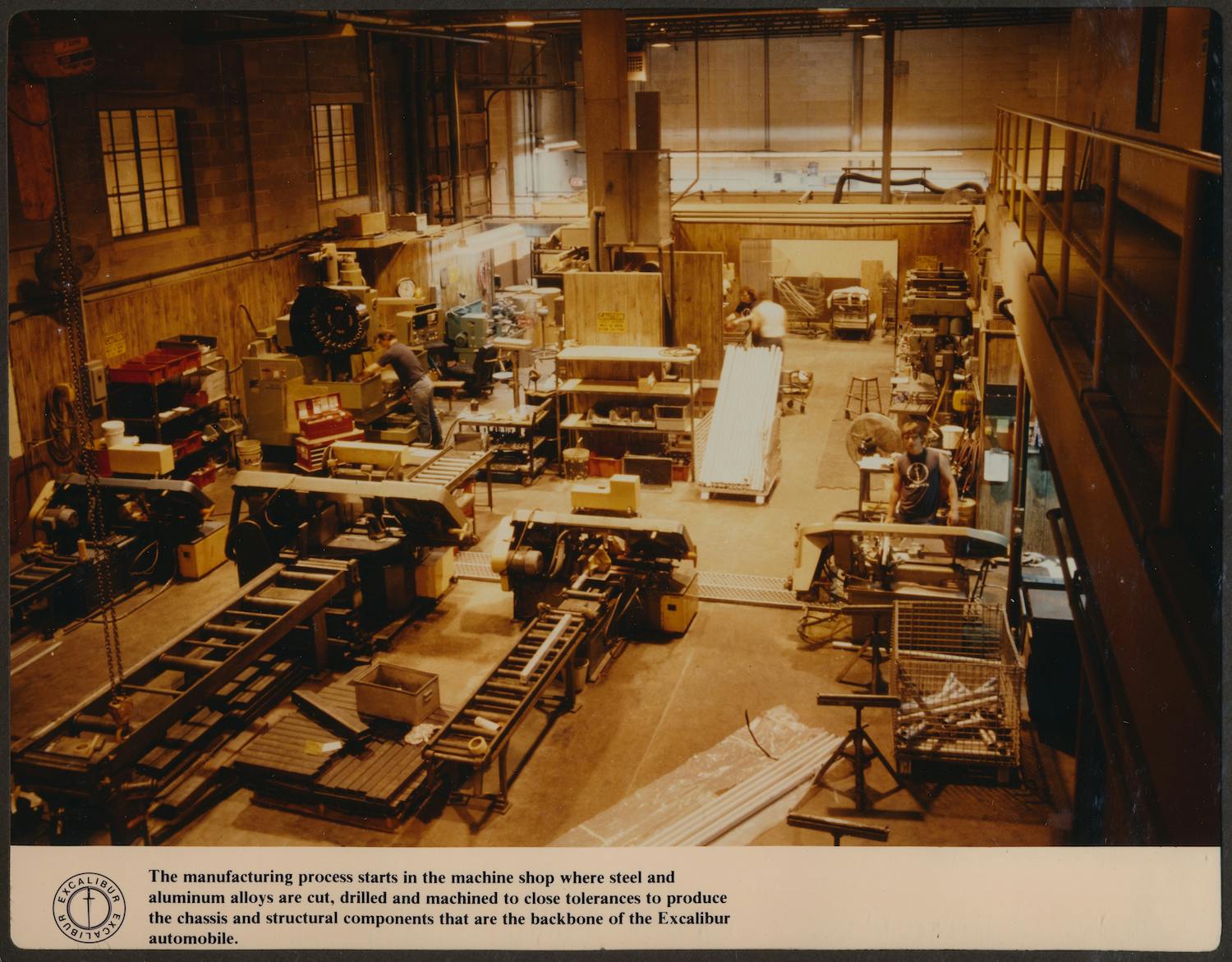

As the company overcame early issues with the Series II cars, Excalibur production began to rise. The Milwaukee area had scores of skilled tradespeople who supplied the company with parts. The task of coordinating these suppliers sometimes proved difficult, however.

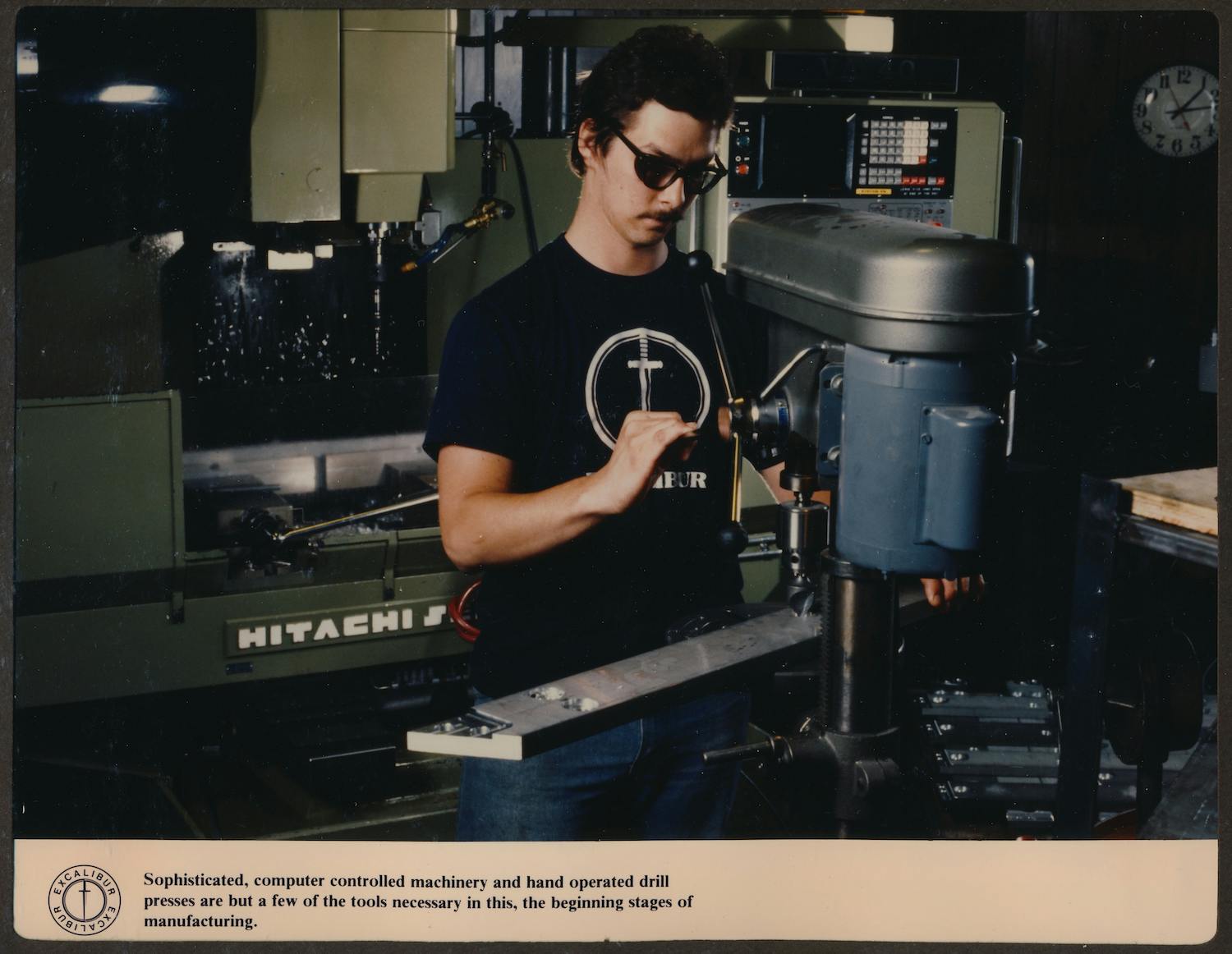

“I decided we should have our own machine shop and do things in-house, instead of running back and forth somewhere, where you’re trying to get something designed,” Alice says. “We tried to do as much stuff ourselves, in-house, as possible.”

She became the right-hand woman to Dave Stevens, who oversaw the cars’ engineering. Both capable and outspoken, she had no problem arguing with her boss.

“David’s a typical engineer, I guess,” she says. “‘More parts is better,’ instead of ‘the best part is no part.’

“So because I wasn’t an educated engineer, I could look at something and be able to give it the K.I.S.S. In the automotive industry we call that, ‘Keep it simple, stupid.’ So instead of having nine pieces here, these three will do … Less things to break, you know.”

One example is the maddeningly ornate front bumpers, which have as many as 44 pieces to assemble. To avoid the hassle and cost of chrome plating and to prevent corrosion, the bumpers are actually aluminum, and the massive grille was made from polished stainless steel. All chromed parts came from third-party suppliers.

“We’d have some battles sometimes, because I’d think it didn’t need all these pieces. Or sometimes, if something didn’t work quite right after testing it, because he’d make it [work] once and say, ‘Okay, that’s done,’ and I would test it … And he’d always add something, and I’d say, ‘Dave, Dave! Stop!!’”

Of course, Excalibur Automobile Corporation couldn’t make powertrains in its Milwaukee shop, so it continued to work with General Motors to source engines, transmissions, and various other parts like rear ends, brakes, spindles, and suspension pieces. GM only asked that Excalibur get its approval for any modifications to the hardware. Many of the parts came from the Corvette and the Camaro but were tweaked to meet the needs of Excalibur models. In what seems like an unbelievable scenario today, GM would allow Excalibur to order small batches of customized parts, meaning the same company that produced millions of transmissions a year would stop to build a special order of 200 separate units just for a shop in Wisconsin.

Decades later, Alice says many Excalibur owners have run into trouble with ignorant mechanics.

“Everybody thinks ‘Oh that’s not a problem, it’s a Corvette.’ No,” she says, shaking her head. “The tolerances for things like the bearing load are going to be way different. A Corvette weighs 2000 pounds, and this is 5800 pounds!”

As low-production vehicles, Excaliburs could skirt certain government regulations, but they couldn’t avoid the mandate to use DOT-approved headlights and tail lights. Without the capital to design ones from scratch and wait for government approval, the company had to find an existing design that looked good and was legal to use.

To this day, Alice still holds a grudge against auto safety advocate Ralph Nader for making their jobs harder.

“Mr. Nader was a pain in the ass,” she grumbles, shaking her head. “That was his job, to be a pain in the ass to autobuilders… He wouldn’t okay anything else, no matter what we tried, if it didn’t have side marker lights … David had to deal with all of that.

“I’m glad I didn’t; I probably just would have punched somebody.”

(Although Ralph Nader never officially worked for the Department of Transportation, his non-profit Center for Auto Safety heavily influenced government policy. However, it is highly unlikely that he personally approved or rejected vehicle lighting designs.)

“The only approved tail-light that he would approve of was Volkswagen,” said Alice. “That’s why people think it’s a kit car, I think.”

Which brings up another particularly sore point for her. Although Excalibur models used some familiar parts, the vehicles are not something an average Joe could put together in his garage over a few weekends. These are production vehicles with unique VINs, hand-built by skilled craftsmen. They are most definitely not kit cars.

Continue to part two of Alice’s story here.

Check out the Hagerty Media homepage so you don’t miss a single story, or better yet, bookmark it.

I liked the early roadster but this car became a bloated mess later on. I recall a school mates mom bought their father on around 1980. It just looked too much kit car.

A local has an early model two seat and that car had it better to the original thinking.

Will part two touch on the subject of the Excalibur Sport Carrier trailer? Information about the history of these trailers would compliment this article about the company.

YOU GO ALICE ! Why is it that the name Alice is almost always linked to women ahead of their time? The VW lights most definitely downgraded such a remarkable automobile and that’s a shame for all the blood, sweat and tears put into it. Thinking that the glass side marker lights off travel trailers of the time would be sufficient with chrome half moon retainers to shield the drivers and passengers from the light and look far classier than the VW. But I get it NADER was a five letter word to the automotive world. Great Story!, Thank You.

Without Alice we all would be in deep shit – not getting parts for these cars we love