In the Moment: Just keep swimming

Welcome to a new weekly feature we’re calling In the Moment!

This all started in Slack, the messaging software we use for staff communication. Several weeks ago, Hagerty’s editor-at-large, Sam Smith, began kicking off our mornings by plopping a random archive photo into the main chat room.

In addition to being a lifelong student of automotive and racing history, Smith drinks a lot of coffee. Each photo he dropped into the conversation was accompanied by a few paragraphs of caffeine-fueled explanation.

We liked these drops a lot, so we’re sharing one here each Thursday. Enjoy, and let us know what you think in the comments! —Ed.

**

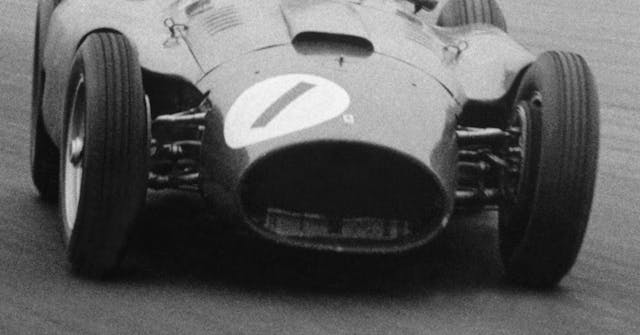

Formula 1, Silverstone, 1956. Silverstone is an English track, the home of the British Grand Prix. It is also on the site of an old airfield, an RAF bomber station active from 1943 to 1946. The track surface began life as the perimeter roads and taxiways of that airfield. This was a common thing after the war, especially in England, where decommissioned air bases littered the country.

The man at the wheel, though! And those tires! That’s why we’re here.

This is Juan Manuel Fangio. He is driving a Ferrari-Lancia D50. The car was designed by an Italian-Hungarian named Vittorio Jano. Jano’s engine designs helped Alfa Romeo dominate grand-prix racing between the wars, and his work helped give birth to Ferrari’s legendary “Dino” V-6. The dude is as important as Italian automotive engineers get.

Jano drew up the D50 while working for Italian carmaker Lancia. Neat company, if you aren’t familiar. Lancia gave the world the first production five-speed gearbox, the first production V-4, and the first production V-6. It also produced machines like the Fulvia and the Aurelia, which you should probably google right now simply because they are each understated and gorgeous.

Lancia specialized in a certain kind of distinctly Italian elegance in engineering, and the D50 was no exception. The car was introduced in 1954, chock with innovation: The engine, a 2.5-liter V-8, was a stressed part of the Lancia’s tube frame. It also sat offset—canted at an 8-degree angle—from the D50’s centerline, which allowed it to be mounted lower in that frame. The gearbox, a five-speed transaxle, lived behind the driver, which let him sit lower.

Still, the panniers are the cool part. Note the big blister of bodywork on each side of the car. Those are fuel tanks. At the time, F1 cars were front-engined, with fuel tank in the rear, behind the driver. It worked for packaging, but it also put a significant amount of changeable weight over or behind the rear axle.

Short version: Race carries on, car uses fuel, car’s weight changes as fuel tank empties. More important, weight distribution shifts. A full tank places a much larger percentage of the machine’s total mass out back. Handling balance would shift over time, sometimes drastically.

The D50’s tanks were genius. First, they served to fill the air “hole” between the front and rear wheels. Left untreated and unchecked, this hole is an aerodynamic handicap. It produces drag, promotes instability, sends air into a tizzy. Modern F1 cars must also run their wheels without fenders and so fix the problem with induced vortices. Wings and other body elements are utilized to build relatively stationary masses of air between the wheels, so the incoming air “sees” a solid space. (I learned more about this a while back in this interview with an aerospace engineer. It’s fascinating.)

Second, there was that change in weight carry. The D50 was more balanced than the average F1 car of the period. In race cars, balance is everything. It impacts handling characteristics but also tire use, driver fatigue, even acceleration and braking. Those tanks were heavy and put weight outboard and relatively high, where a race car does not like weight. It didn’t matter; the benefits were worth it.

The D50’s first race came in 1954, at the Spanish Grand Prix. The last points event of the year. The Lancia was brand-new. Even the idea behind it was new. Hell, for that matter, Lancia had never before entered a grand prix. They just hired Jano, trusted him, asked him to look forward, let him run with it.

The car landed pole. Then fastest race lap.

Then, of course, it broke. But that debut!

Maybe this isn’t impressive! Maybe you are looking at this spindly old thing of aluminum and skinny tires and thinking, Well, sure, who cares, slow old car, dead guy at the wheel!

Fair. Seventy years back is a long time. A brief digression for perspective: We are talking here about a 1300-pound device made of small metal tubes and propelled by 260 horsepower, or 285 in later trim. No seatbelt or safety equipment of any kind. Top speed was more than 185 mph. The tall, narrow tires were rock-hard by modern standards. Each offered a contact patch the size of a few postage stamps.

The driver wore something like street clothes. Helmets were cork-lined. Often an old polo hat.

On that note, let’s return to the man in the goggles.

Juan Manuel Fangio was a king in this era, one of the people who figured out modern driving before anyone else. The Argentinian is widely agreed to be the most evolved driver of his era—dominant in sports cars and formula cars, in sedans, in all weather. Always calm and relaxed.

When the D50 launched, in 1954, Fangio was a factory driver at Mercedes. Big company, huge budget, lots of success. In 1955, however, the brand withdrew from motorsport. The reason is both tragedy and story for another day. Lancia, for its part, had issues. The Italian company’s production cars were expensive and slow-selling; its Formula 1 efforts had helped drive the marque toward bankruptcy. The Lancia team was shuttered, the cars and related technology put up for sale.

The deal that followed involved—this is such a great list—an Italian prince, the Italian national automobile club, and the family that owned Fiat. Promises were made. Much noise was made about keeping Italy’s treasures at home. The D50s and their technology were given to Ferrari. Fiat agreed to pay the latter 250 million lira over five years.

Ferrari then was not Ferrari now. The marque was young and struggling, and its racing cars were in a fallow period. The D50s and that funding helped set the company on a greater path. More immediately, with Mercedes out of the picture for 1956, Fangio was no longer employed.

Ferrari hired him. The ’56 F1 season held eight points races. Half of them were won by a D50. Three of those wins came in Fangio’s hands. The man also notched pole in six of those races and fastest lap in four of them. Most of all, he won the championship.

The second-place driver that year was British legend Stirling Moss. The friendship between the two is a cool piece of trivia. Moss and Fangio had been teammates at Mercedes and carried huge respect for each other. Moss was one of the best drivers in the world, massively versatile and fast in anything. And yet he believed, until the day he died, that Fangio was better. Quicker, cleaner, smoother.

Fangio was so good, Moss once said, that the older man could lead him around in equal cars, clear speed in reserve, while Moss was driving as fast as he could. How could the Brit tell? Fangio, he said, occasionally took time for what Moss called “lessons.” When the two men drove together, one following the other, the Argentinian would occasionally vary his corner inputs and lines.

At first, Moss assumed the great man was ill or beside himself. Making stupid mistakes. After a bit, though, he realized the changes were on purpose. Fangio was offering a gentle education in driving technique, a series of subtle lessons in the finer points.

Neat, right? Except: This whole scene, Moss noted, more than once played out while Fangio was leading an active F1 race.

Once Moss caught on, he was flabbergasted. More important, he loved the gesture.

The slide in this picture is not dramatic, just a light bit of yaw. Fangio was a master of small inputs. He was also a master when it came to putting a period treaded crossply tire in its sweet spot of slip angle.

Treated properly, tires like this don’t really slow the car when they slide. The details hang on tire compound and construction, but a cornering crossply is typically fastest when it feels slightly less than planted. The result is something like that smudgy forward-outward-tangent feel you get when cornering on roller skates.

Modern tires are radials, and radials are different. Driving a modern car quickly is like scribing a line with a wobbly hand. A small amount of slip is generally necessary; too much, the rubber molecules and tire carcass get into a kind of fight with the pavement. They grab and slow and bind and release, over and over. Lap times rise.

A more obvious but equally cool note: Look where Fangio’s head is turned. He’s looking through the corner.

Now click the image, zoom in, look where his eyes are aimed. Even further to the right. You can basically use that angle to judge the width and length of the corner, even though we can’t see the exit.

Lesson for the day? It’s a two-parter. First: Trust your people. Believe in them, let them take chances, remember Jano.

Second: The car goes where you look. Always. So keep your head up.

Yes, that’s a metaphor.

Have a good day, guys!

—Sam

Sam wrote it, but when it references Fangio and Moss, I’d believe it if it were written by Gomer Pyle. The words and concepts of those two comprise 80% of “how to race” knowledge that makes todays cars and race drivers so fun to watch.

True dat.

Long by some standards, but not prolix. Sam, too, is “a master of small inputs.” I enjoyed every word.

I knew about JMF when I was an adolescent in the ’50s in Mississippi. I must have read about him in Life magazine, as we were not even given small inputs by the local media. Fangio became a personal hero figure, even though I pronounced it with a hard “g”.

“Look there, go there” – the mantra (or should-be mantra) of every motorcyclist…and racing driver.

Yes known it Britain as WYSIWYG (Where You See Is Where You Go)

It’s true that Moss firmly believed Fangio was better than him but I did a series of prints with him in the 1980’s and I got the impression that he thought he may have had the edge in sports cars.

IMO, the introduction of wings brought with it the beginning of the end of formula racing as interesting spectator events. During F1s golden age, drivers could be seen to be working to overcome the limitations of their cars as they cornered and braked on the ragged edge. Today’s F1 cars go flick flick flick through chicanes as if on rails; long, lurid slides are a thing of the past.

My rule set would allow one gallon of gas station fuel per 10 race miles, high volume production car tires, a minimum weight including fuel and driver, a maximum body width, and no external wings.

Autocrossing is different and a good driver in a Corvair could go through a slalom as a series of tail flicks even on Blue Streaks. Drifting meant something quite different (was called “oversteer” then) from tire shredding of today but about a 20 degree “tail out” meant being pointed down the straight and hard on it while still in the corner. Have always thought tire smoke meant going slow but then also developed “unladen understeer” in the early 70s. Had a B/P FI split window I learned a lot from.

A great article, written beautifully, with style. Thanks for the moment.

Formative years were then and those were my heroes. ” began life as the perimeter roads and taxiways of that airfield.” Same could be said of south Florida then Sebring began as an airfield but were many others most claimed by the ARCF then SCCA.

Remember going to a driving school and being told you could not drift a Formula Ford. Was rong. True, harnesses make driving fast easier particularly in a “street” car but back then the cockpits were so narrow that you were really wedged in and dictated arms out, no Barney Oldfields need apply, and leaning back 30-40 degrees helped aerodynamics. Helped to be 5’10”, Dan Gurney had real problems.

Learned early on to shift with either hand but interestingly the pedals were usually the same unless the gas was in the middle. Versatility was the name of the game since were so many different cockpit layouts.

Was a great time to grow up in Florida & Nassau Speed Weeks was a short flight on a Mackey DC3 (sometimes passengers had to help turn around on a small island).

The Best Period of any generation, in my view, many greats but he was MAN!!!!

Exquisite. Thanks again, Sam.

Had the privilege & honor of meting Senior Fangio at Road America years back when he was the Grand Marshal for one of the vintage weekends. He was signing books and having a GRAND time of it.

What a great gentleman, and he was amazed that so many people remembered him, and wanted his autograph.

At the Concours event on Fri, night, which was hosted by a Jaguar club, the comment was made Why J.M. Fangio as Grand Marshal ? I looked at the club president, pointed out that everybody there was a racing enthusiast, and asked “Who was World Champ 2 years ago?” Nobody knew, to which I pointed out that EVERYBODY knew who Fangio was !

One of my most treasured books in my library is the one he signed for me.

Interesting note, the organizers of the event would NOT let him take a solo lap !

Fangio, “El Chueco”, was simply the best and spent his best years, physically, not driving F1 because of WWII. Imagine what he could have accomplished? He won his last championship when he was 46!

Well put, Tim. I agree with you 1000%!

Fangio made his “bones” racing a 1937 Chevrolet 2dr sedan in really long distance races. He could drive any car masterfully. He was truly a “Car Whisperer.” He could gentle a car through a four wheel drift, lap after lap.

See the picture of him doing so in the 1957 French Grand Prix. It is breath taking even as a still photo. Let us not forget his fantastic come from behind victory in the 1957 German Gran Prix.

You can take every F-1 Champion with the possible exception of Clark, Stewart, and Senna, and put them all in equal cars. Fangio would defeat them all. He was in a different zone, apart from the others.

There is a reason why no other Modern Era driver is called Maestro.

As an author myself, I agree with Tim Howie. Beautifully written article about a man and the sport we love.

This plain and simple, is one of the best short articles I have read about Motorsports. Kudos to author Sam Smith. It combines anecdotes about the best Formula 1 and Sports Car racing drivers and the best auto companies and constructors of their time in the mid 1950’s to the early 1960’s. All from an author who knows what he is talking about and also knows how to tell a good story. His detailed analysis of a picture of Fangio lightly sliding a car through a corner, the angle of his head and the focus of his eyes, is alone worth the read. Thanks for doing it.

This is a wonderfully written and researched article. And I’ve been panic chastised for my habit of looking through a corner by many high speed, brake pumping floor pushers that simply don’t trust my licenses and driving history. I look where I’m going, not where I’ve been; at 80+mph I’m looking at least a half mile ahead. At 140, from the passenger seat you have no view of what I’m looking towards. Unless there’s mechanical or tire failure, and I keep my equipment immaculate, you’re safer with me at 140mph than when you drive yourself and kids at 40mph, phone in face, kids distracting, and food/drinks/disciplinary hollering all at the same time. No one speaks to me- it’s a mandatory thing- once we pass 100mph. I hold current SCCA and NHRA licences, and at 63yoa have decades, not weeks, of very high speed driving experience. Lived in Europe, ’80s, donchakno. One of my pet peeves is the excessively thick A pillars on modern cars, my ’04 GTO has A pillars to support semi truck weight. I find myself jinking my head back’n’forth just to see around the driver’s side A pillar at speed. But it’s quiet and I can travel safely in the empty wastelands of North Dakota right at the Goodyear’s speed rating. Wouldn’t do nor recommend in more populous states, but here I’ve run 140+mph for over a half hour at a time alone. Yeah, if I make THE MISTAKE or a spendy Goodyear Eagle goes, I’ll be balled up in the Aussie metal and my brother gets everything. But I do the work on my car, trust Goodyear, and have decades of training and experience. In ND, you might travel 30 miles and see not one other vehicle. Been there, live there, done that. I’m not worried about making a mistake, I worry about a blowout or mechanical failure that hurts me out in the sticks where, in North Dakota, there simply isn’t anyone. No traffic, no help. The car could burn with me trapped, no one would see the fire. This is real. But long, straight, smooth untravelled roads are real, too. I look ahead, but am not psychic, just an enthusiast. Cali, New York, crowded Chicago and Indianapolis. Within 20min of Fargo, I have access to untraveled, ruler straight roads that go to the horizon. And use them with no need for “looking through the corner”. Their aren’t any.

Bring that Bugatti and top end it. No one will know.

Fangio is an amazing driver. The skill to take something so traction limited to the limit is amazing to watch.