In 300 miles, Bugatti’s misunderstood EB110 won my heart

Sometimes there’s just not enough time to form a lasting impression of a classic car. Maybe the day was too short, the road too congested, or the owner too wary of handing over a precious car. But I still clearly remember my first—and best—Bugatti EB110 drive, 16 years on.

It was summer 2006, and though production of the new Veyron had— finally—begun several months previously, there had been few chances for anybody to drive one properly. Then, after months of making a nuisance of myself to anyone who’d listen at Bugatti, the chance came to drive a new Veyron 16.4 at the historic Bugatti HQ in Molsheim, France.

Great! But how about going a step further, I suggested. How about driving its spiritual successor, the EB110, across Europe to meet the new hypercar? And perhaps throw in a prewar Type 57 too? Even on the phone I sensed eyes rolling in the Bugatti press office …

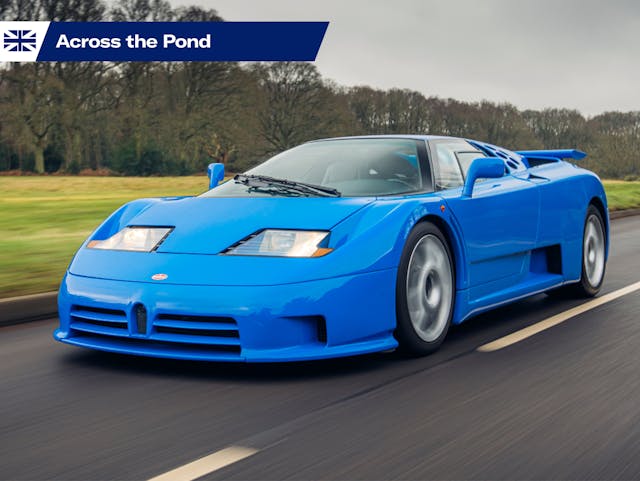

So that’s how I came to meet with Helmut Pende, owner of a 1995 EB110 GT, in Munich for a near-300 mile drive on autobahns and back roads all the way to Molsheim, stopping just once to refill the twin fuel tanks. And that’s how my preconceptions of the EB110 fell away—and I fell in love with this misunderstood machine.

The EB110 story has all the classic elements of the supercar in its heyday: the prolonged gestation, the mercurial company owner, the talented but volatile Italian designers and engineers, and the flawed but ultimately inspirational final product.

Bugatti Automobiles had produced some of the greatest road and race cars ever seen, but the 1939 death of founder Ettore Bugatti’s engineer son Jean, while testing the company’s Type 57 “Tank” race car, had begun a decline that World War II and the passing of Ettore in 1947 inevitably hastened. Bugatti Automobiles stumbled on until 1952, with various revivals attempted unsuccessfully during the following years.

In 1987, though, a protracted deal to buy the Bugatti brand was finally completed by Romano Artioli, an Italian entrepreneur who had run successful Ferrari dealerships and Japanese car importers. His aim was to build a new supercar worthy of the Bugatti name, and for this he worked with former Lamborghini engineers at Tecnostile, recruited Paolo Stanzani, and courted various big-name designers, eventually settling on the renowned Marcello Gandini. Never one to do things by halves, Artioli also commissioned a brand-new factory in Campogalliano, Modena, Italy.

By 1989 the first plans for the car were revealed, built on an aluminum honeycomb chassis, with—by today’s standards, at least—awkwardly angular, stubby styling. Artioli wasn’t happy with the chassis or the bodywork, and it wasn’t long before Stanzani and Gandini had departed from the new company.

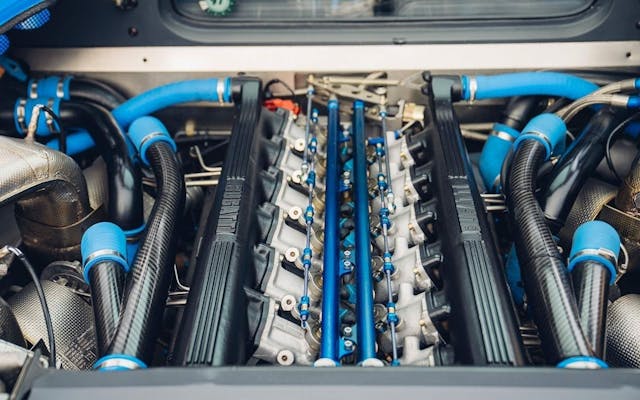

A carbon-fiber chassis replaced the aluminium honeycomb and the styling was revised to the less extreme, more timeless look with which we’re familiar today. Eventually, the all-new EB110 GT was unveiled on September 15, 1991, on the 110th anniversary of Ettore Bugatti’s birth. With a 3.5-liter quad-turbo V12 and six-speed, four-wheel-drive transmission, it was the fastest production car in the world. Six months later it was followed by the more powerful, lighter, and even faster EB110 Super Sport.

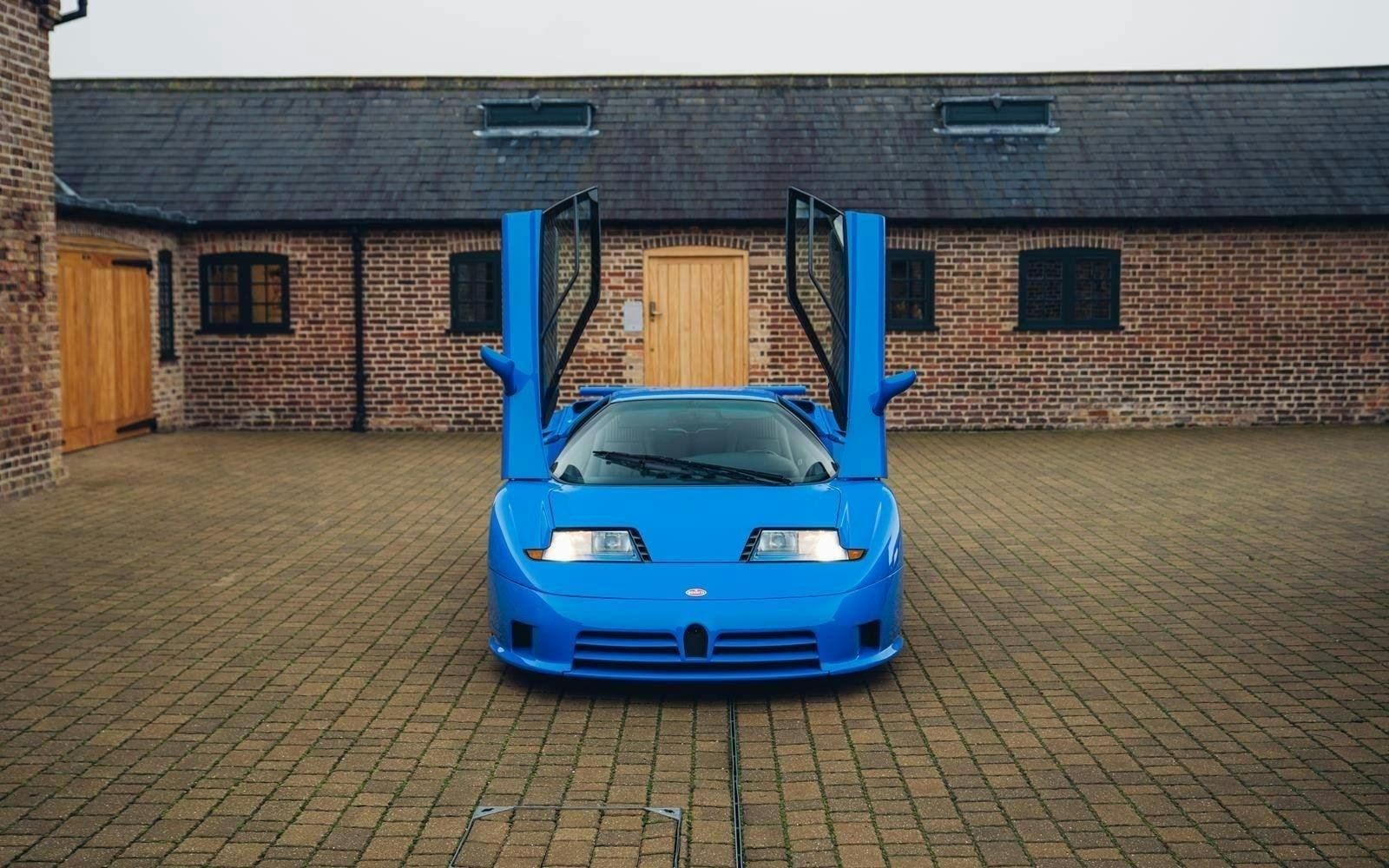

For all that, when I first saw Helmut Pende’s EB110 GT, I was struck by how understated it looked. Unlike, say, the Jaguar XJ220, the EB110 no longer looks like a large car, and the lack of aero add-ons keep it as subtle as any 200-mph-plus supercar could ever be. Swinging open a scissor door added a bit of drama and revealed a surprisingly opulent leather-clad interior—we’re not just talking seats, door cards and dashboard, but headlining and footwells in hide as well. Only the slightly out-of-place chunk of wood around the instruments shouted low-volume supercar; it felt much higher quality than that in a Lamborghini or Ferrari of the period.

The door needed a hefty pull to close—in case you’re wondering, a button on the leather-clad sill releases the EB110’s door from inside—and that 560-hp, all-alloy V-12 fired up quickly after the briefest whirr from the starter motor. It sat at a smooth, quiet idle, feeling refreshingly civilized, as I tried the controls.

It was all as expected for a supercar of the era. Heavy clutch and gearshift? Check. Restricted headroom? I’m afraid so. Limited view in the rearview mirrors? Of course, though who’s moaning when the view in the interior mirror was of the engine? The V-12 needed more revs than expected to pull away but was quieter than expected … at first.

As confidence rose, so did the speed, and with that, the noise levels. With a shove on the accelerator pedal the EB110 exploded forward with a violence at odds with the initially civilized feel, and the soundtrack took on a more mechanical feel, with the coarse roar of the exhausts accompanied by whines from the four turbos, chattering from the wastegates, and whirrings from the four-wheel-drive transmission. It wasn’t deafening but it was certainly louder and even more exciting than anticipated.

The EB110 just kept pulling ever harder on its long gearing, feeling unstoppable. Back when it was new, Autocar found the EB110 would hit 60 mph from a standing start in 4.5 seconds, reach 100 another 5.1 seconds later and storm onto a remarkable 212—but the 30-to-70-mph time of 3.3 seconds best told the story of the EB110’s fantastic usability.

As the speed rose, what felt like a heavy car at low speed became more fluid, the steering more responsive and the suspension riding the bumps without a single creak or shudder from the bodywork. In fact, it was the overall solidity and quality of the EB110, along with the outrageous performance, of course, that really struck me as we drove fast across Germany into France. The carbon-fiber construction, a first at the time, worked well to absorb the loads from the stiff suspension and added to the feel of quality.

Michael Schumacher famously crashed his EB110 Super Sport into a truck, blaming inadequate brakes. Now clearly I’m no Schumacher, but the GT’s brakes felt powerful enough for my own fast road driving.

The four-wheel drive was similarly controversial at the time, adding weight to a car that was already heavier than any supercar other than the Lamborghini Diablo VT. Was it necessary? Now we’d say it wasn’t, but back then, when electronics weren’t as sophisticated, it was viewed as the only way to safely handle such huge power. As it is, it almost certainly takes away from low-speed agility but adds to high-speed confidence and that impression that the EB110 is unstoppable.

It’s a long way from perfect, with the almost total lack of luggage space and the weight (3571 pounds for the GT, 3126 for the Super Sport) most often cited as its major flaws. Not that it had long in this world. By the time the EB110 had made its motorsport debut in the 1996 24 Hours of Daytona, Artioli had overstretched himself to develop the four-door EB112 and buy Lotus Cars (the company) at the same time as his huge Suzuki dealership was hit by an unprecedented rise in the Japanese yen.

What a sad and perhaps predictable end, but not one that should detract from the car itself. When we rolled into Molsheim we parked alongside a Veyron and Bugatti’s own Type 57 Atlantic recreation—and the EB110 looked perfectly at home and just as worthy of the famous logo and horseshoe grille as both its predecessor and its then-new successor.

David Lillywhite is editorial director of Magneto magazine, which offers fresh perspectives on the world’s greatest cars.