Smithology: As if he knew something we didn’t

I saw the tops of the front tires and flashes of blue. Then I fired up that borrowed Formula Ford and drove parade laps for a crowd.

Drive a race car slowly, you occasionally drop out of rhythm, think a little too much.

I was thinking a lot, for the record.

Daniel Sexton Gurney was a romantic. This is happy for me, because it means we have something in common. He called his race cars Eagles and insisted they be styled like birds, even when that last bit was less than practical. More important, he looked forward, always, even when it was difficult. History has given us a host of legendary race drivers who doubled as team owners. Few so embodied the distinctly American notion that anything is possible because … well, why not?

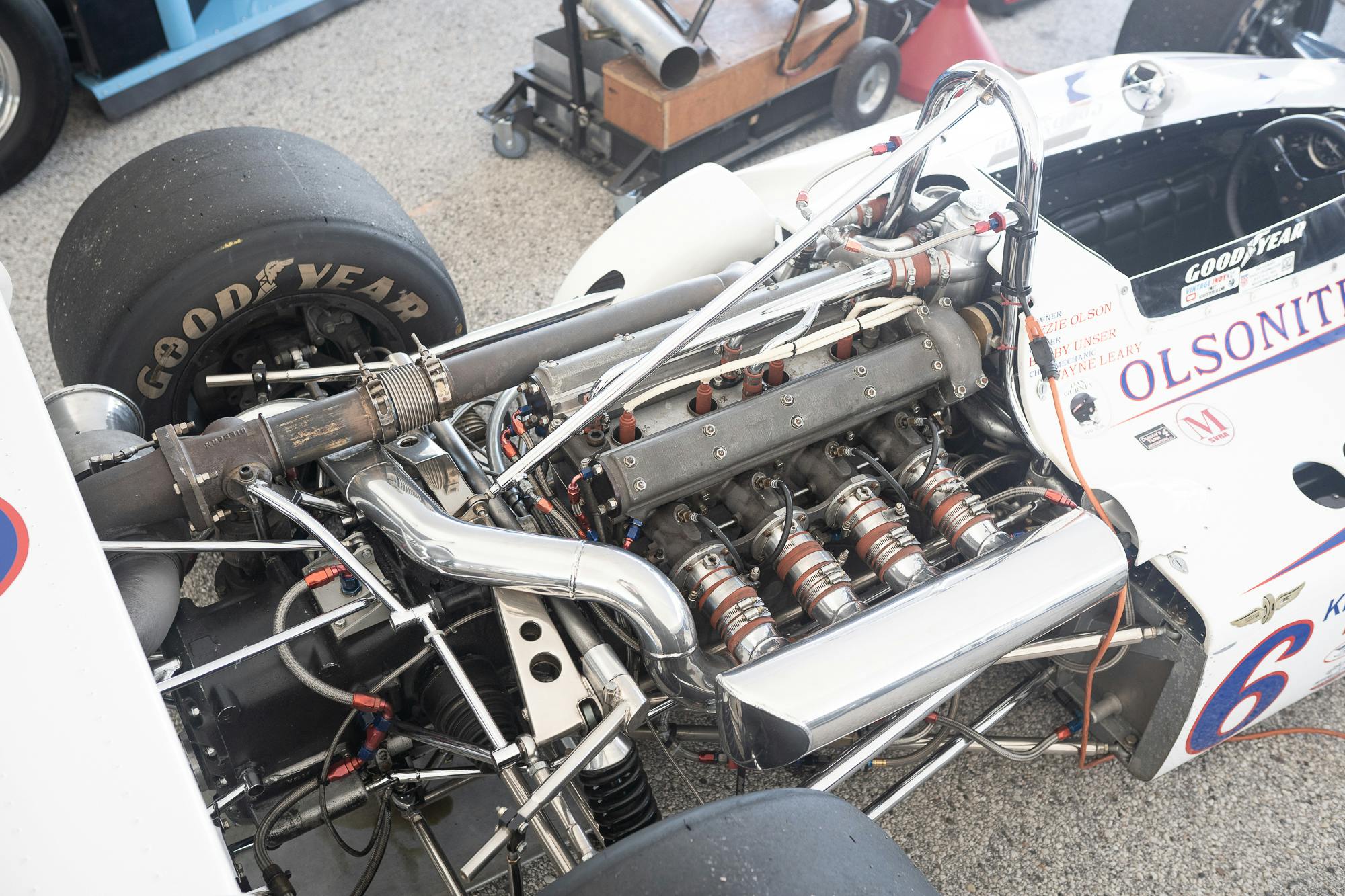

Lists are for shopping and resumes, but the stats hold weight. As a driver, Gurney won in Formula 1, in sports-car racing, in the Trans-Am, in Indy cars, in the Can-Am, in NASCAR. He drove, then he drove and built his own cars, then he left the cockpit to run his team full-time. From 1965 to his 2018 death, his Santa Ana shop, All American Racers, birthed a staggering amount of revolution. He remains the only American to win a Formula 1 race while driving a car of his own construction. A device he invented in a virtually offhand moment of trackside ingenuity produced the greatest one-year speed gain in Indy 500 history (more than 17 mph, 1972) and is still used widely in aerospace and motorsport. He won Le Mans for Ford in a golden age for each, driving a GT40 with A.J. Foyt. His Toyota GTP cars of the 1990s produced more downforce than any current F1 car and held the overall lap record at Laguna Seca for years. Books have been written on the footnotes and still not told the whole story.

Eagles were top-shelf pro tools, built for the best drivers in the world. AAR’s only real project for amateurs was a single model of Formula Ford, 1977–1978. Just 13 were made, aimed at what was then the peak of international club racing. Dan wanted to give something back, the story goes, so he pointed his world-beating staff at weekend speed for normies. (Imagine charging NASA with blueprints for your kid’s paper airplane.)

Those cars were officially named DGFs, Dan Gurney Fords. People called them Eaglets. By the early 1970s, the big Eagles were making 750 horses from a four-cylinder and clocking around Indy at 195 mph. Like all Formula Fords, the DGF used an engine design shared with, among other things, the Ford Fiesta. It went far slower than the Indy machines but reeked of story greater than your own.

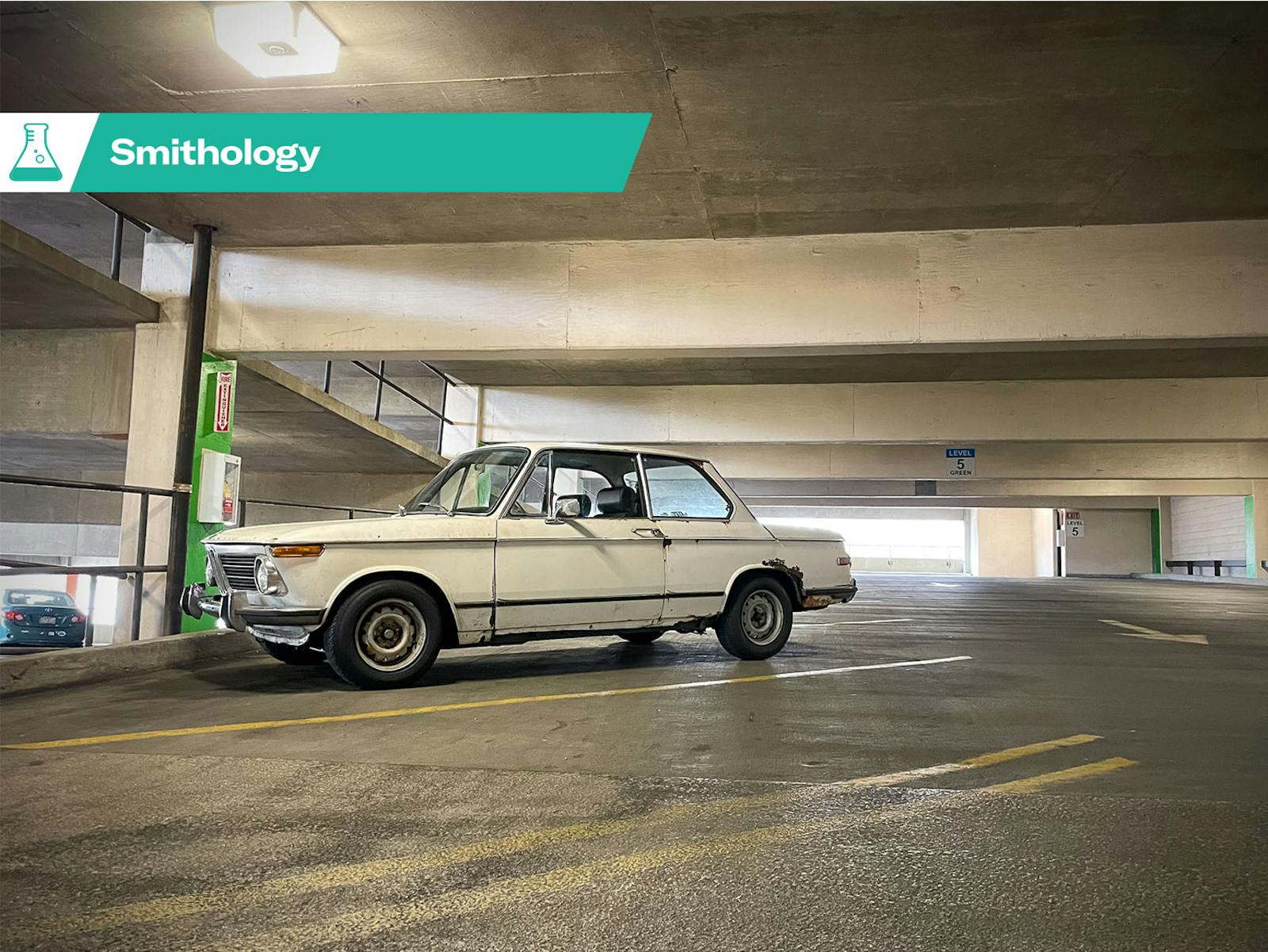

I drove a big Eagle for photos once, at Indianapolis, a ’72. Strapping into that blue Eaglet at Road America a few weeks ago felt somehow more special. Maybe it was simple fitness for purpose—I am a small driver, not a big one, at least figuratively. I have never flung a car around an oval at a buck-ninety, but I do know what it means to go club racing, and I love that meaning to pieces.

Old Formula Fords are mostly steel tube and fiberglass. Imagine a 115-horse coffin. The driver lies nearly flat behind the wheel, feeling large as houses. With the DGF, the swirl of appeal outstripped purpose and name—it pulled in his people, that Santa Ana idea factory, California’s perpetual and shining optimism. DGF frames were built by Phil Remington, the Le Mans-winning AAR engineer who had sorted Cobras and GT40s for Carroll Shelby. He worked for that Texan first and Gurney later, helping Dan develop dozens of Indy cars but also those Toyota GTP missiles and the mind-bending Nissan Delta Wing. Rem is gone now, too, but his hands helped build much of the diaspora of American motorsport, and there he was, there he is, in that cockpit, in those welds, making another car for Gurney, but also for goons like you.

Twenty-eight other Eagles were shipped to that track this summer. That figure represented more of the great man’s work than had ever been assembled in Santa Ana or anywhere else. Each machine was privately owned, brought in for the occasion. Dan’s adult sons, Alex, Danny, and Justin, flew in, as did a host of AAR legends. There were designers and one-time shop hands, even Stretch, the team’s impossibly tall truck driver. Royalty among them was Kathy Weida, the twinkle-eyed charm cannon who began her AAR life as Dan’s secretary, then rose to vice president. (That was Dan: Anybody can be anything if you’re good enough, so why not you?)

I shook her hand and grinned like an idiot. Not least because she was grinning, as Dan had grinned, infectious.

Gurney died in 2018, at 86, but he was in that paddock as if walking and breathing. Most of what I heard there revolved around how the man treated others, how he held that rare combination of good cheer and trust that made you want to work harder and better.

There were moments, they say, when this approach gave amusing ends. That was usually when things were going well, the team or car far ahead of the pack. He’d get antsy, poking around the garage, looking for things to fix. The team would grow understandably annoyed: For Pete’s sake, Dan, just leave it alone, we are winning!

Still. That was how he got where he got.

On getting places: I would not have met that Eaglet without generous friends. Rick Dresang and his adult son Jacques live in Milwaukee. They own that DGF I drove, plus a few Indy Eagles. The Road America event was their baby, a way to give back to a name meaning so much to so many. Weida once called the Dresangs’ shop “AAR east,” an honor that only hints at their efforts to research and support the Gurney legacy. Jacques is an erstwhile karter and former Spec Miata racer who gets a tattoo of Dan whenever he wins a championship. Rick is a former snowmobile racer who tells stories with so much warmth, they could pass for hugs. Along with their chief fabricator, Paul Jay, the men restore Eagles to high standard.

Around a dozen of the gathered Eagles were fired up for parade laps. This meant two 20-minute sessions over a single weekend, packed into the business of Road America’s flagship vintage race, the Weathertech Challenge. Many of the cars were literal museum pieces, so the Eaglet and I met that first session slowly, out of respect. Later, the Dresangs suggested 80 percent—eight-tenths of flat-out—might be alright. The unspoken notion being that Dan liked certain ideas, and few more than his race cars going faster than you expect.

So the next time, I went faster. No risk, just a small open-wheeler and America’s most grand-dame of road courses on a bright July day. The Indy cars wore tires like oil drums. I followed one close enough to smell the exhaust, had it water my eyes like a chemical fire. It felt like walking on stage at the Met.

Some experiences seem built to address how we think about each other. The trick, I think, is remembering that all history was once a vibrant memory for someone, and that each of those memories is like a boat full of holes. Retelling stories helps keep the names alive—bailing out the boat, so to speak—but in the long run, civilization keeps moving. Water eventually meets the gunnels. The facts remain, but the vibrance falls beneath the waves.

I wish I could tell you why that simple little car left me so drenched in feeling. For a shop I never visited, a guy I never knew, machines I am too young to have seen run in anger.

After the demo laps, I walked to the grass inside Turn 1, to watch. Later, Jacques went out in that same Eaglet, on a sunny Wisconsin afternoon, in a field of two dozen other Formula Fords, in a race of no consequence whatsoever. Then he drove the wheels off the car and hung it on the podium.

Vintage racing is like little league, with the fun the point and the trophies an afterthought. Jacques got a little second-place medal on a ribbon, which he gave to Kathy Weida. I am told that she then went to Siebken’s, Elkhart Lake’s hallowed old racing bar a few miles away, where she wore that medal on her neck for the rest of the night. As if it the achievement were somehow more than just another old race car fighting the good fight. Or maybe that’s the point.

I met Dan once, briefly, near the end of his life. He was in Detroit, receiving an award for lifetime achievement. There was a lunch, and I ended up at his table. At a break in the discussion, I asked why he made his cars so pretty, when others were happy simply being fast. The bird thing.

He smiled, as if he knew something I didn’t. Which, of course, he did.

“If you have a chance to make something beautiful,” he said, “and you don’t, well, what does that say about you?” A wink.

I like to think Dan treated that shop like a family. The miracle of the guy’s life is how knowing the story makes you feel part of it. Even for the rest of us, even if we were stuck on the outside, just watching and marveling and tracing the path, trying like hell to keep up.

Thanks for writing so well about something/someone so deserving!

Dan’s F1 Eagle is, far and away, the prettiest race car wver built. I saw him (barely) at the 1968 Nurburgring F1 race (very, very wet, and far too few laps on the long course), but what I saw, I fell in love with. If I win a lottery, one of those is on my shopping list.