Midget Race Rookie: Our editor tastes a fresh flavor of competition at the Chili Bowl

Sooner or later, I was going to get punched. I knew this. Yet I still didn’t see the wallop coming. Holding an unlikely second place in my first-ever midget race—which was also my first-ever midget race inside a building—a following driver slammed my rear bumper, ramming my brain bucket into the headrest and forcing the car, already drifting sideways on the loose dirt, into a spin. Rookie training, Chili Bowl–style.

Now 36 years old, the Chili Bowl packs nearly 400 midget race cars and their crews under the roof of an expo center in Tulsa, Oklahoma, which becomes the American epicenter of four-wheeled dirt combat every January. It regularly attracts pro drivers from multiple disciplines as well as young jockeys hoping to catch the eye of IndyCar and NASCAR team owners. The resulting hyper-aggressive stew, run on a quarter-mile dirt oval, brings some 15,000 spectators on multiple nights. The 2021 NASCAR Cup champion and two-time Chili Bowl winner Kyle Larson calls the Bowl “the greatest event in the world.”

Here’s another interesting thing about the Chili Bowl: Anyone can enter, including any amateur who has never even sat in a midget race car. Like me. I’m 51 years old and have decades of club racing experience but zero time in midgets. I thought that slinging a midget around a dirt track, spitting mud, dicing with other drivers would be the most riotous thing a lifelong driving enthusiast could do behind the wheel. In hindsight, I had no idea how intimidating this form of racing could be.

Ray Evernham told me that modern midgets “are like damn little Formula 1 cars.” Evernham was Jeff Gordon’s crew chief during the NASCAR salad days, so he knows something. The cars have evolved over the years, mostly for safety, but they remain simple, tube-frame, pint-size open-wheelers. They’re roughly 7 feet long, weigh an even thousand pounds, ride on solid axles front and rear, and have 350 or so horsepower from highly tuned four-cylinder engines. They more or less have the power-to-weight ratio of a supercar skateboard.

Midgets have long been the backbone of American racing. The first midget race was held in 1933 at Loyola High School stadium in Los Angeles, but the class didn’t take off until after World War II. That’s when companies like Kurtis-Kraft offered DIY midget kits for about $1000 to feed the same postwar daredevil and tinkering urges that spawned hot rods. Raced on everything from ball fields to horse tracks, the accessible and hard-to-master midgets became stepping stones to Indy. Mario Andretti raced one, and it’s still a path to the pro leagues.

So I called Landon Simon, a professional sprint car driver and team owner who also runs midgets. Simon had a car, and after I shared my bona fides, he offered it for $7500 including entry fee, tires, and fuel. Crash damage was, of course, extra. Considering that I’m not getting younger, and my alternative January activities included snow shoveling, I sent Simon a $4000 deposit.

During Chili Bowl week, dozens of races whittle down what this year amounted to a 396-car field. There’s practice on Monday and racing every afternoon and night until the big finale on Saturday. The heat races, which vary in length from eight to 20 laps, are elimination rounds with, usually, the top four drivers advancing. Regardless of where you finish during the week, you’re automatically eligible to run on Saturday, the weekday races determining which Saturday qualifying race you start in. A driver can theoretically recover from a poor weekday finish by winning races and advancing to the final, winner-take-all feature that kicks off Saturday night.

In 1987, Chili Bowl founders Emmett Hahn and Lanny Edwards rented Tulsa’s Expo Center for $18,750. The Expo Center is a massive convention center that was erected in 1966 to cater to Tulsa’s economic engine, the oil industry, which needed a large space to peddle drilling rigs. The building is 1180 feet long and nearly 400 feet wide. The roof is supported by external cables, like a suspension bridge, so the interior is devoid of support columns. If the Empire State Building were laid on its side and slid indoors, only the top few floors would stick out. There’s enough space for both a track and paddock.

Despite scheduling the first race on Super Bowl weekend, Hahn and Edwards attracted a local company, Chili Bowl, to be the headline sponsor. Expenses that year to build the track, staff the event, and attract drivers via tow money exceeded income by $20,000. The two eked a small profit the third year. “Things accelerated when Tony Stewart showed up in 1993,” said Hahn. As Stewart moved up the racing ranks to IndyCar and NASCAR, he continued racing at the Bowl, raising the event’s stature. Stewart finally won the Bowl in 2002, and every year, more drivers arrive. To accommodate, Hahn and Edwards added days to the event. The rent went up, too, to $293,000. Chili Bowl, by the way, ended its sponsorship in 1994, but by then, the name was too ingrained to change. Lucas Oil is now the main sponsor.

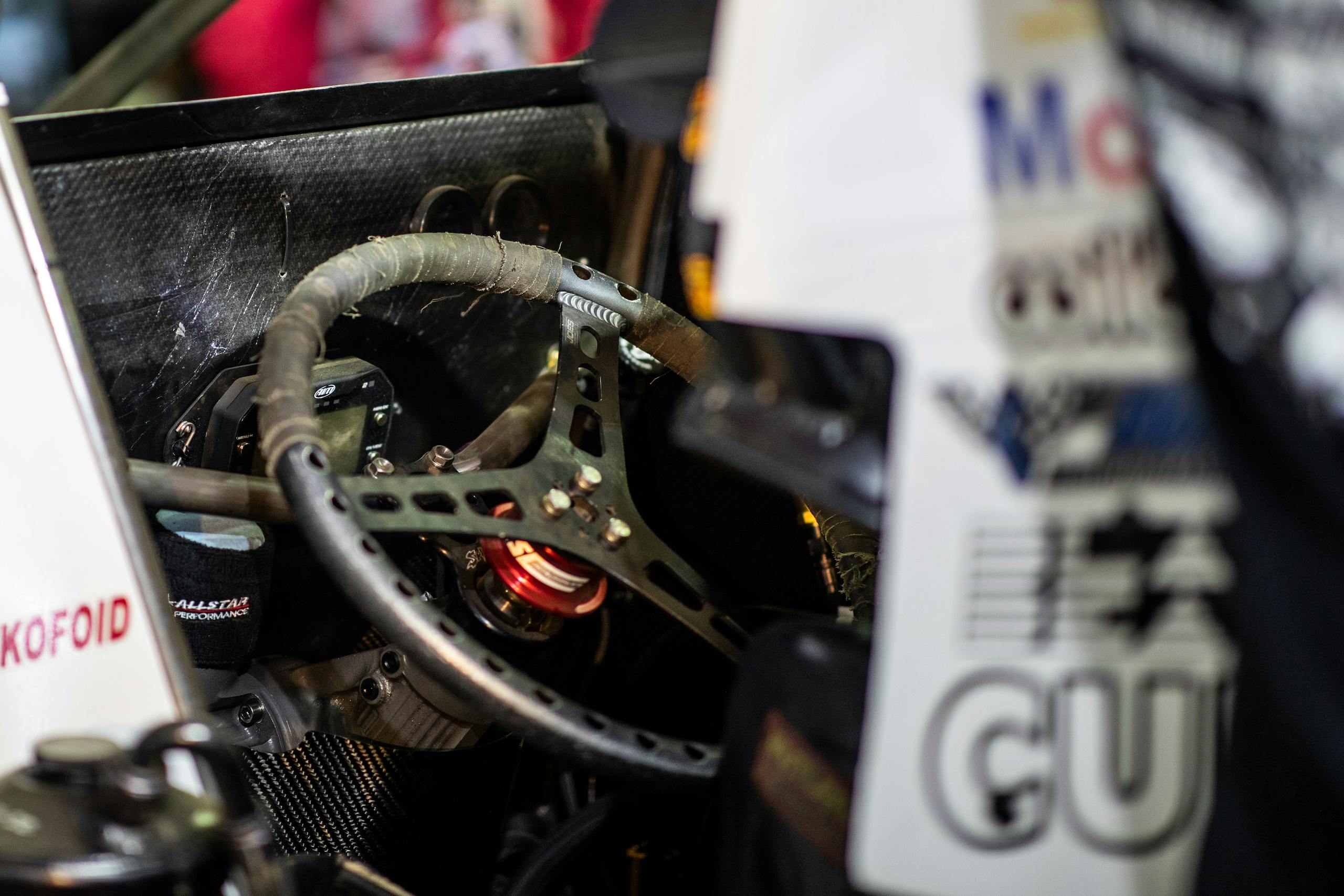

In front of the main Expo doors, there’s a golden 75-foot-tall statue of a Paul Bunyanesque character—the Golden Driller, lest anyone forget how Tulsa butters its bread. After locating Simon and my car and donning my gear, I climbed on top of the rollcage and wedged myself, with effort, down and into the cramped seat. These stubby cars don’t offer much fore and aft room. I felt like I was in a coffin sized for Frodo Baggins. My knees touched the firewall. The gas “pedal” is made from two short metal bars that you slide your foot into. The brakes operate via a similar metal bar on the left. There is no recline in the seat; you sit vertically, like you’re at a dinner table. Simon installed the steering wheel, which is positioned horizontally like a bus’s, such that my, ahem, middle bulge was only an inch away from the rim. After much tugging, squeezing, and cursing, Simon cinched the belts. I could not move my legs, only the ends of my feet. My elbows were stopped rearward by the seat, thus I could only hold the wheel at the 10 and 2 position. Midgets do not have a transmission or a clutch. They are either in gear or out, which is selected by a short lever on the right. There is no onboard starter, either, so a squadron of ATVs and Jeeps push the cars to bump-start them.

Practice, my first time in the car: Strapped in, about to go out, I could hear cars on the track buzzing like a swarm of atomic hornets. I’d watched practice earlier in the day, the cars whizzing around the track in tight packs, and realized I would be a slow, rolling obstacle. Seated in this overpowered, rabid wolverine of a machine, wondering if I could even control it let alone not ruin someone else’s race, reminded me of what an official said during the driver’s meeting. “If you’re gonna fight, he said, “do it between turns 3 and 4.” I was the most nervous I’d ever been in a race car. A clergyman walked up and, no kidding, fist-bumped me. What did he know?

The thump from behind signaled that a Jeep was starting its push. I wiggled my left hand under my right arm to engage the gear shift while countersteering because the pushing sends the car sideways. As instructed, I opened the fuel valve under the steering wheel and flipped the ignition switch. BWAAAAAAAAAAAPP!

The car surged forward into a rutted mess of divots, holes, pasty clay loam, ridges, and sections polished from previous cars. Where to go? Half a dozen cars flew by, the drivers goosing the gas to presumably check the traction. Green flag! I mashed it, the sound rocketed to 11, and my senses went numb. Dirt pellets hammered my face shield. Gas gas gas gas … now turn! I tried the brakes and my helmet ping-ponged against the headrest. A car zinged by on the right, maybe—I couldn’t really see. Fumbling to locate a tab on my face shield, I ripped off a plastic layer. Vision restored, ah—turn! The car continued straight. OMG, my brain screamed, here comes the wall! Another car zoomed by on the inside. More dirt on the face shield. Oh yeah, the wall. I hit the gas and the back end stepped out. Turn right … panic … lift off the gas … more panic. The car snapped back toward the wall. Gas! Stay in it, boy! There was a car on its side on the front straight. Yellow flag. Slow. Breathe. Breathe.

Overturned car righted, the green flag dropped again. I accelerated to Turn 1, stabbed the gas, and drifted. Stay on the throttle. You have to—the track is like ice. I was going sideways but felt like I was barely moving. Straightening the wheel, I rolled off the gas to try to gain traction. Three cars winged by in unison. I tried the inside, avoiding the lip that marks the infield. Nope, so I went outside next. The dirt there is always loose and clumpy, and the car jerked left and right, fighting the dirt. The wall! Checkered flag … breathe. Breathe.

So that was practice. I’d done four laps at speed, about a minute. Track time is scant at such a big event, but even so, my brain was frazzled. I sought advice. “Midgets on dirt are not finesse machines,” Simon told me. “The more aggressive and confident you are, the better they’ll feel.” Professional NHRA drag racer Cruz Pedregon was, as luck would have it, also part of my team. The winner of two Funny Car races in 2021, Pedregon regularly accelerates to 320 mph in under four seconds. When I asked if he had any tips, he said, “You’ve never done this before?” Then he exhaled. “Man, you’re crazy.”

Risk in motorsport is hard to calculate. Watch a midget race and you’re bound to see one do an unplanned cartwheel. The flips are so common that the Chili Bowl scoreboard counts them. Typically the driver walks away, but in 2016, NASCAR up-and-comer Bryan Clauson was killed in a midget.

Thursday, my race day, arrived. The 78 cars running were first split into nine eight-lap heat races, with starting positions determined by lottery. I was in heat two, fifth position. The rolling start kicked into gear at about the middle of Turn 4, and I was immediately bumped from all sides. I didn’t drive into the first turn so much as I was pushed into it. The noise, the pelting dirt, the fear—it was all the same. Even though I had fleeting moments of some competence, the notes I took afterward are a garbled mess. I remember several crashes and caution periods where we idled around long enough that my legs cramped. Every restart meant more jostling and more contact. I was shoved around like the rookie that I was. My “keep it clean” strategy paid off, however, as attrition meant I finished where I started, fifth.

That was good enough to vault me past the “D” mains and into one of two “C” mains, where I lined up seventh among 12 cars for the next 12-lap race. Once the mains started, around dinnertime, the stands were full and a pickup with two young women standing in the bed holding a huge American flag paced the field. Music blared. A rubber chicken was added to the top of a cone standing on the front straight. The chicken went airborne when the car in front of me clipped it at the start. Naturally, there was a crash. As we idled around, I noticed there were roughly three lanes in the corners. I considered the outer lane, with its soft, lumpy piled dirt, to be my personal danger zone. The middle was polished and extremely slick. That left the inside, with enough loose dirt for traction. The lane to aim for. The risk, however, was the raised lip, about 18 inches high, where the track surface transitioned to the infield. I watched other drivers take this line, hook a front wheel on the lip, and spin.

I can’t say I made a conscious decision about what came next. I only recall, thanks to a GoPro on the rollcage, that at the restart, I darted to the inside and stayed there, carving the turn as much as sliding sideways. Two cars ahead went in the middle, but slid to the outside berm and bogged down. I shot past them and into second place. I held my line for the next few laps, maintaining this unlikely position, wishing I had a mirror to see the Roman chariot race happening behind me.

Mirrors, however, are illegal, so I didn’t see the incoming punch that I previously mentioned. In Turn 3, bam! A hard whack from behind pushed me sideways and the front wheels climbed the inside lip. I kept the car from spinning, but my new trajectory carried the car up the lip and into the infield. What now? I had no idea, so I kept the gas pinned, cut the rest of the corner on the infield, launched off the lip, and back on the track into fourth place. Two cars immediately passed, the checkered flag waved, and I finished sixth. My night was over.

There seemed to be two camps in the paddock: those who had a chance to win and the others who were there to race and party. Hahn told me pros come because of the relaxed atmosphere. During the week, I saw NASCAR professionals Christopher Bell, Chase Briscoe, and Kyle Larson, IndyCar driver Conor Daly, and former NASCAR champions Bill Elliott and Jeff Gordon, who patiently waited in line with everyone else to buy a bowl of chili. They were hanging out. “They get to enjoy the race track like they did before they got famous,” said Hahn.

During my downtime, I caught up with Taylor Reimer, a 22-year-old college student who turned a 10.95-second lap, the fastest on her day. “I’ve always liked going fast,” she explained, as though that is all it takes. Reimer, who is also a University of Oklahoma cheerleader and one of several women racing, ran with Keith Kunz’s team. Kunz brought five trucks and 15 crew members to handle a dozen cars at the Bowl. He’s known as something of a talent scout for NASCAR, so, consequently, he has a full stable of young drivers with sponsors or parents who can afford the roughly $150,000 for a year of midget racing.

A brand-new competitive midget costs about $100,000, mostly due to the engines. The most common are Toyota Racing Development four-cylinders, which are roughly half of a Toyota NASCAR engine. They run on alcohol, are fuel injected, and rev to 8700, producing about 350 horses. The engine runs $70,000, about the cost of a C8 Corvette.

My son and I watched from the grandstands, which are close enough that you can see the drivers’ steering movements. NASCAR ace Christopher Bell won the “A” feature race that day. As Bell sailed sideways along the outer berm throwing dirt, he minutely and slowly turned the wheel. His small corrections were a stark difference to my frenetic sawing, a sign he gracefully steered as much with the throttle as with the wheel. Bell drove several lines that night, switching from the inside to the outside as the track surface changed, every lap a new experiment. That is what dirt-track fans and drivers love about this type of racing; it’s improv. “Dirt drivers,” commented Evernham, “have a different set of skills from those who only drive on pavement. They have to adapt every lap.”

All 396 drivers run on Saturday, a massive logistical undertaking. The first green flag, for the “O” feature, waved before breakfast. Don’t ask me to explain this, but my previous results put me in the “K” race. As I sat in the car waiting, Simon leaned in with this sage advice: “Hey, your back bumper is all sorts of messed up. Why not try and use the front one for a change?”

There were 16 cars in my 10-lap race, which I knew was likely my last. Again, confusion and mental overload. In Turn 2, a car passing on the inside clouted my left front wheel, sending me outside and into the wall. The impact was light, but the front wheel climbed the wall, pitching the car skyward. Expecting a tumble, instead, mercifully, I slammed back down. With a couple of laps to go, I risked driving the outside berm, just to see what it felt like. At this point, the berm was perhaps 10 feet wide, the outer edge being the wall. I buzzed down the back straight toward Turn 3, fighting my self-preservation instinct to lift. There is no try to this maneuver, only full commitment.

The only thing I’m sure I did was mash the gas at the start of the turn. The car pitched sideways into the piled dirt, the rear tire digging in. This made the car rotate out of the slide and back toward the wall. More gas. I arced around again, feeling weightless and the same giddy thrill I had when I did my first donut in snow. Before I could try again, the race ended and so did my Chili Bowl. I later learned that the driver who bumped me was three-time World of Outlaw sprint-car champ Sammy Swindell. It was almost like shaking hands with the Pope. Including practice, I had driven fewer than 50 laps at speed. That’s less than five minutes, which sounds like nothing, but it felt like years. In that brief time, I learned more about driving and car control than I have in the past 10 years.

Later, the crowd was in full party mode, swaying to the nightly airing of Garth Brooks’s “Friends in Low Places.” A track worker attempted a cartwheel before a race and instead landed on his back. The crowd erupted. Every race was high drama. Who would advance, who would be knocked out? With only 24 spots in the finale, you could beat 372 other drivers and still not make the main show. The action was constant.

At 11 p.m., the top 24 drivers started the 55-lap finale to crown the Chili Bowl champion. The flip counter numbered 64. Three-time winner Chris Bell led from pole, followed by NASCAR regulars Kyle Larson and Ricky Stenhouse Jr. On lap 37, Tanner Thorson cut across Bell’s bow and took the lead, and that was that. Thorson, 25, previously won the 2016 USAC Midget Championship. Under the “achievements” section of his Wikipedia page, the top line now reads, “2022 Chili Bowl Nationals Winner.”