Media | Articles

On Yellowstone’s 150th anniversary, we drive a 1936 bus that toured the park’s 2.2M acres

Los Angeles County is a 15-hour drive from Yellowstone National Park, so it may seem like an odd place to get up close and personal with a classic Yellowstone tour bus. Nevertheless, Winslow Bent is stoked to be here, and so are we.

Bent, 48, is an enthusiastic, quick-witted Chicago-area native with a name better suited to a blues musician. Make no mistake, however, Bent prefers the mechanical note of a vintage engine. He’s a classic truck dude, and his instrument of choice on this sunny California morning is a 1936 White 706 that’s as rare as a 1950s Gibson Flying V. Like that vintage guitar, this thing can really sing.

“Low compression, totally quiet,” Bent says of the vehicle’s 96-horsepower, 318-cubic-inch flathead-six 16A engine, whose mellow personality is the polar opposite of its owner’s. “It doesn’t have much power, and it’s not in a hurry. You could sneak up on grizzly bear in this thing.”

Which, of course, is the point, considering where it worked for most of its life. “It does exactly what it’s designed to do, and it does it quietly,” Bent says. “Can you imagine running a Detroit diesel in a national park?”

Almost as absurd as a chef losing his job and launching a new career in truck restoration—without even meaning to.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

Bent, owner of Legacy Classic Trucks in in Driggs, Idaho, grew up in the Windy City suburb of Lake Forest, Illinois. “As an impressionable young man, I enjoyed watching the sparks fly inside my father’s stainless-steel fabrication plant,” he says. “And I handed my dad tools while he restored a World War II vehicle.” Both experiences helped Bent become a classic car enthusiast who started a car club in high school and even did a little street racing—“But I got out of that in a hurry,” he says, with no further elaboration.

“I was a very serious enthusiast with no money,” Bent continues. And following the advice of his father, he entertained no plans of making any of it in the automotive field. Instead, he moved to Colorado to attend culinary school … where he quickly developed a taste for four-wheel drive vehicles. Years later, in 2008, after losing his job as a chef, Bent decided to throw caution to the wind and build a Dodge Power Wagon “the right way.” He took the finished truck to auction and sold it immediately. That led to showing another Power Wagon at SEMA in 2010, and, before Bent knew it, he had as much restoration and custom work as he could handle.

Considering the trucks that he has built in the years since, it’s easy to see why Bent continuously refers to the 26-foot-long Yellowstone bus as a car. “You want to see a truck—I’ll show you a truck,” he says with a smile. “Let’s just say this is one of the smaller ones I’ve worked on.”

Bent welcomed this trip to California, as it gave him the opportunity to get reacquainted with the White Motor Company 706. With a deep appreciation of history, he purchased the bus from a client, and about a year ago he finished restoring the body and refreshing the engine. The bus, wearing Yellowstone Park Company #386, was soon purchased by the Montage Hotel in Big Sky, Montana, which uses it to transport guests on a fascinating ride down Memory Lane. Montage, with the help of IBP Media, Inc., was kind enough to loan the bus for this trip to Los Angeles, which also included a day of filming with celebrity car collector Jay Leno.

Bent clearly has a close relationship with #386. “It was an honor to help bring it back to life,” he says. “It means so much to people, and there’s so much history in it. I’m really fired up to drive it again.”

For the uninitiated, driving this thing is no easy task. With a four-speed unsynchronized manual transmission—also called a crash gearbox—double clutching is required … and the technique is close to an art. To double-clutch shift, you put the transmission into neutral and rev the engine just the right amount before shifting into the next gear. Even the most experienced drivers don’t get it right every time, and the inevitable grinding of gears results in a dreaded squawk from beneath the floorboards.

Bent demonstrates. After depressing the clutch pedal, he explains, “You wait a few seconds, listen—that sounds about right—and then you jam it.” He celebrates the good shifts and laments the bad ones, sometimes verbally, sometimes with a simple groan when he misses the mark. “Now you know why they called the Yellowstone bus drivers gear jammers.”

Commenting on the vehicle’s leisurely pace—it’s most comfortable at about 38 mph—Bent jokes, “We’re shooting mostly still photos, right? God bless you guys. We’ll be fine.”

The Yellowstone bus is once again proving to be the perfect tool for the wilderness paradise that made it famous.

Yellowstone National Park, currently celebrating its 150th season, was established in March 1872. Spread over 3472 square miles (larger than Rhode Island and Delaware combined), it lies mostly in Wyoming but also nudges into neighboring Montana and Idaho. Early travel within the park was by horseback, but eventually guests would arrive by train and be transported to the various inns on the property by horse-drawn stagecoaches. According to geyserbob.com, a Yellowstone Park history site, the Yellowstone National Park Transportation Company was one of several stagecoach companies serving the park—and one that would ultimately have the most historical significance. It began in 1891, and seven years later it was taken over by Harry Child and two partners. Child eventually became the sole owner.

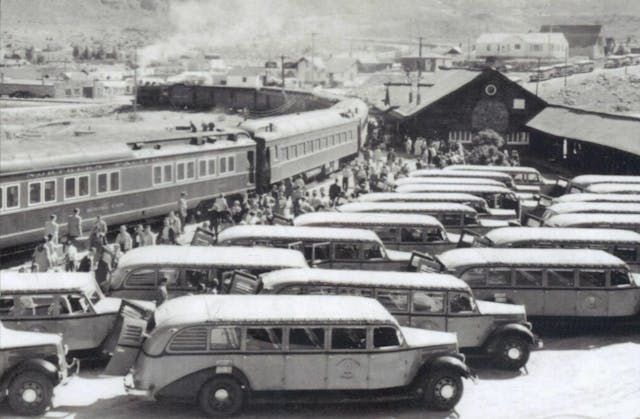

Separate stagecoach companies served different areas of the park, but when the National Park Service was created in August 1916, the NPS moved to consolidate concessions, and Child was selected as sole proprietor of both transportation business and onsite hotels. It was a turning point for guest transportation, as Child immediately began transitioning the fleet to motor cars, negotiating with Cleveland’s White Motor Company to replace the stagecoaches for 1917.

After agreeing to a new 20-year contract with the NPS, Child purchased 100 10-passenger White TEB open-sided buses and 17 White seven-passenger touring cars, which allowed guests to explore Yellowstone’s many canyons, geysers, rivers, hot springs, and forests, as well as reach their hotel accommodations. From 1918 to ’24, Child added 104 more 10-passenger White buses, as well as 47 seven-passenger touring cars. He began purchasing White Model 15/45 tour buses in 1920.

Sadly, in March 1925, disaster struck. Fire broke out in the Mammoth Hot Springs main bus barn. Nearly 100 vehicles were lost, and damages were estimated at almost $500,000—nearly $8.3 million today. Fortunately, another 200+ vehicles in another barn were spared. Child restocked the fleet, once again partnering with the White Motor Company. The convoy soon included a number of updated, 14-passenger White Model 614 models.

Child’s long-standing relationship with White would prove beneficial, even after his death in 1931. Five years after Child’s son-in-law William Morse Nichols took over the business, and at the end of the Yellowstone National Park Transportation Company’s 20-year deal with the NPS, a soon-to-be-iconic motor coach would become the transportation face of Yellowstone … and, as it turned out, of other Western national parks as well. A group of NPS concessionaires representing Yellowstone, Glacier, Zion, Yosemite, Grand Canyon, Mt. Rainier, and Rocky Mountain negotiated with Ford, General Motors, REO, and White before agreeing to purchase White 706 open-top buses for their parks.

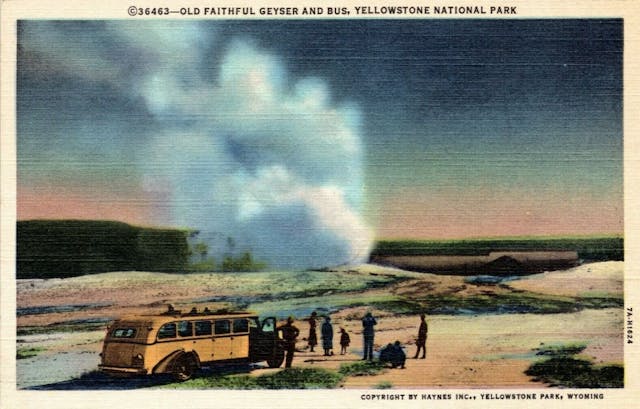

Crafted by innovative designer Count Alexis de Sakhnoffsky, the 706s compensated for their lack of power with aerodynamic good looks. With a chassis by White and bodies by Bender Coach Builders, the buses were—and still are—visual masterpieces, exactly what you’d expect from a man who won five consecutive Monaco Grand Prix Medallions for auto design.

“This stood out mostly because of the front clip,” Bent says of Sakhnoffsky’s design. “It has that cool wedge shape. The radiator was low compression, so you could get away with the smaller radiator and grille. And the open-air top makes perfect sense—you’re in Yellowstone Park, so you’re going to be looking up a lot.”

Other notable features on Sakhnoffsky’s stylish creation are two squared-glass windshields, lantern-style rear running lights, bench seats with multiple ashtrays (you wouldn’t want anyone tossing a cigarette out the window), and a rear “blanket box” for—you guessed it—blankets, just in case the passengers got cold. The Yellowstone buses also had dual license plate holders in back because they were registered in both Montana and Wyoming. Unlike the similarly famous—and red—Glacier Park versions, Yellowstone buses have barn doors in the rear and a compartment for passenger luggage, since traveling throughout Yellowstone’s expanse took days to complete. Other 706s, like those at Glacier, have an extra row of seating and an additional side door.

Bent says the vehicle’s canvas top was supposed to be rolled back and packed into a convenient metal tray at the rear, but tourists began using it for something a little more enjoyable. “They discovered that if you rolled the top all the way back past the tray, you could fill the tray with ice, beer, and other beverages.”

Although Sakhnoffsky’s design looks more modern than its 1936 date suggests, the 706’s frame is built of wood, which Bent finds impressive. “Eighty-eight years later, that wood is still original. That’s testament to how rugged these things are. The average bus has 600,000 miles on it—on roads that weren’t paved and with 14 passengers dripping ice cream everywhere. These buses weren’t supposed to last this long, but they’re tough as hell.”

One of the problems Bent faced while restoring the body was galvanic corrosion, an electrochemical process that causes corrosion wherever aluminum and steel meet. “The side trim is steel, and the doors are aluminum, so the combination means it essentially eats itself, and that’s a problem.” The corrosion resulted in the need to take extra steps to protect the paint; Bent admits it was the toughest paint job he has ever done.

On the other hand, Bent didn’t touch the interior. “You can do too much with a restoration, and I drew the line there. It just looks so good the way it is.”

The bus is one of 98 White 706s built for the Yellowstone National Park Transportation Company and one of 27 ordered for 1936. Another 41 were purchased in 1937, 20 the following year, and 10 in 1939. When America entered World War II in 1941, pleasure travel in the U.S. declined; four years later, when the hostilities ended, Americans were excited to buy and drive their own cars on family adventures. Each park was ultimately faced with deciding the fate of its White 706 bus fleet, and they didn’t walk in step. For example, while Yellowstone sold its entire fleet of 706s in the 1950s, Glacier Park held onto its fleet and till operates 33 of its original 35 “Red Jammer” buses.

These days, with nostalgia being a huge draw, Yellowstone buses have made a resurgence. In 2007, the park’s concessionaire bought back eight of the 706s, which have been updated by placing the original bodies atop 1999 Ford E-450 (van) chassis. Although Bent understands why it was done, he staunchly refuses to make those kinds of modifications himself.

“We’re not taking these cool old trucks and modernizing them,” he says. “Of the 80 or so left, 50 to 55 are no longer original, so that makes it even more important that the remaining buses stay the way they are.”

This one, of course, is a member of the latter group, which means that when Bent offers me the opportunity to take it for a spin there’s no way around the double-clutch obstacle. Prior to this moment, I’ve never driven a vehicle that required the technique, or even attempted to operate a non-synchronized manual transmission, which means I’m about to tackle double-clutching on a very rare, very historic, and very valuable Yellowstone bus. Bent encourages me anyway, reminding me that I likely won’t get this opportunity again. He’s right, of course, but I ask for a compromise. We’re parked in a large office complex with several parking lots that aren’t as intimidating as the Los Angeles streets that Bent has just negotiated, so I feel a little more comfortable doing a lap here. Sounds like a plan, he says.

“It’s the most fun you can have at 38 mph,” Bent promises, knowing full well that I’ll never go anywhere near that speed. “I kind of like that you can safely jump if something goes wrong.”

Not helping, Winslow. Not helping.

The first challenge is to simply get behind the wheel, which isn’t as easy as stepping up and sliding onto the bench seat. A huge parking brake is positioned on the floor beneath the large steering wheel, essentially between the driver’s legs, and you have to be a bit of a contortionist to get your right leg past it. Once settled, there’s an ignition button on the floor that you activate with the heel of your right foot. With the engine running and the parking brake off, it’s time to engage the transmission and move this bad boy forward … carefully. I’m immediately aware of something else that calls for additional focus: the bus requires wider turns than my Volkswagen SUV back home in Michigan, and operating the steering wheel demands some muscle. In my mind I look like a seaman trying to quickly close a watertight door before the ocean rushes in—turn, turn, turn, turn—then I repeat that in the other direction to quickly straighten the wheels.

Bent urges me to go faster and try my hand (foot?) at double-clutching. Expecting the worst, I follow his instructions and—what the?—I do it correctly. Not even the slightest bite from the stick. “There ya go!” he says. Of course, overconfidence when driving a White 706 is neither advised nor merited, and the bus reminds me why.

When we finally come to a stop, reality quickly rears its head. I can’t reverse the dang thing, nor do I want to—certainly not without breaking into a sweat—so that it can be safely placed onto the trailer bed of the Mack truck that delivered it to L.A.

Bent is quick to rescue me … just as he has rescued this beautiful yellow bus.

“I grew up with toy models of these Yellowstone buses as a kid, so to say this has been a special build would be an understatement,” he says. “This thing is such a blast. I love it.”

He’s not alone, either. It dawns on me that I have fallen for it too, even though I’ve never been to Yellowstone Park, and until today I’d never seen a White 706 in person. This vehicle, which survives decades past its original mission, thanks in part to Bent’s dedication, is easy to love. The charm of this faithful beast is a happy surprise, too, since the vehicle was built to go completely unnoticed by passengers craning over its sides, hoping to spot a grizzly or while gazing at Old Faithful. In that humble mission, the old bus succeeded decades ago, a faithful chauffeur whose rumbling engine note will never be forgotten.