Supercar Boom! How kids fueled Japanese car culture

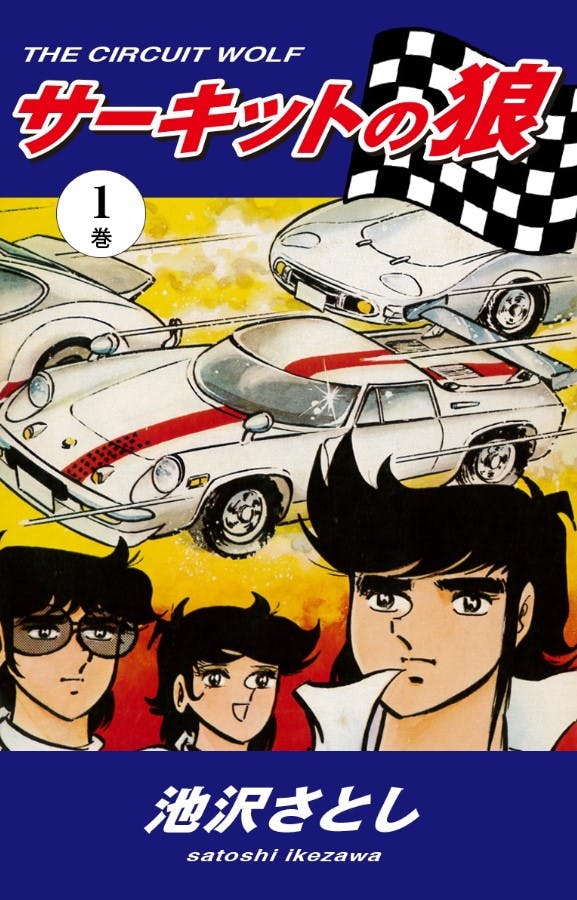

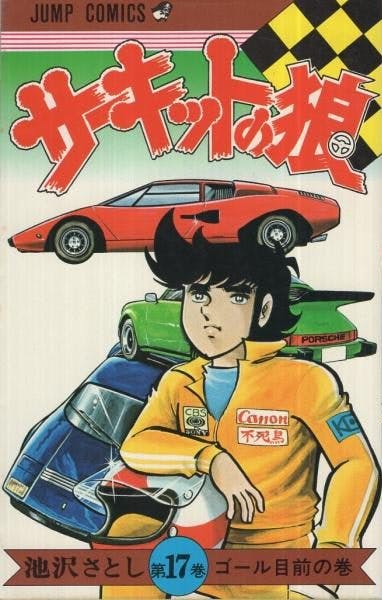

The mid-1970s are known among car enthusiasts for the oil crisis and as a time when performance cars went from fire-breathing monsters to shadows of their former selves. Yet it was during this worldwide automotive turmoil that a supercar boom was born in Japan. Rooted in Circuit no Ohkami, or The Circuit Wolf, a manga serialized in the multi-million-selling Shonen Jump magazine from January 1975 to June 1979, an explosion of supercars captivated thousands of school-age kids and helped pave the way for decades of rich car culture and automotive passion in Japan.

The manga follows the adventures of Yuya Fubuki, a talented driver who races against rivals Sakon Hayase, Minoru Asuka, and others in European supercars of the era. Young readers eagerly memorized the specifications of the Lotus Europa, Ferrari Daytona, Lamborghini Countach, De Tomaso Pantera, and others as the characters faced new racing challenges with each issue.

The Circuit Wolf’s popularity made Japan supercar-crazy. It spawned spinoffs and supercar-themed media and products, including a live-action film, supercar quiz shows on television, and of course, children’s toys. Supercar erasers were a particularly ingenious creation: although shaped like the cars from the manga, they also served as pencil erasers. Emboldened children brought them to school, insisting to their teachers that the little cars were functional—not merely toys.

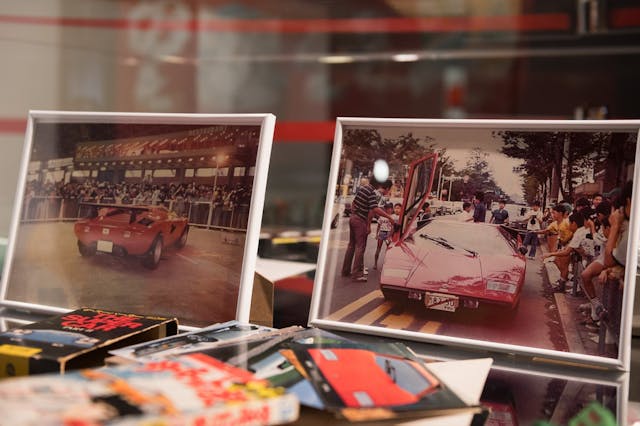

With little enthusiasts seemingly at every intersection, a commercially-astute car dealer came up with a plan to hold supercar shows in the parking lots of supermarkets and baseball stadiums all over Japan. A hastily-bought Ferrari 512BB became the star, and children gathered to watch it and other supercars drive by. For an extra fee, they could even ride in the passenger seat. Kids fortunate enough to live in a city that had a supercar importer (there were few) would flock to showrooms for a chance to photograph these European exotics.

Unfortunately, although perhaps unsurprisingly, all the pop culture fame driven by Japan’s youth failed to materialize into substantial sales for the likes of Ferrari, Lamborghini, Porsche, and others. Manufacturers and importers tried to take advantage of this opportunity to sell supercars in Japan, but the boom soon disappeared, fraying distributor relations for years to come.

It could be tempting to call the supercar boom a passing fad. The toys and events may have faded quickly, but sports cars and racing were now firmly embedded in Japanese culture. The children who pored over the manga’s images in the 1970s became the teens and adults of the 1980s who would drive Japanese car culture to the next level.

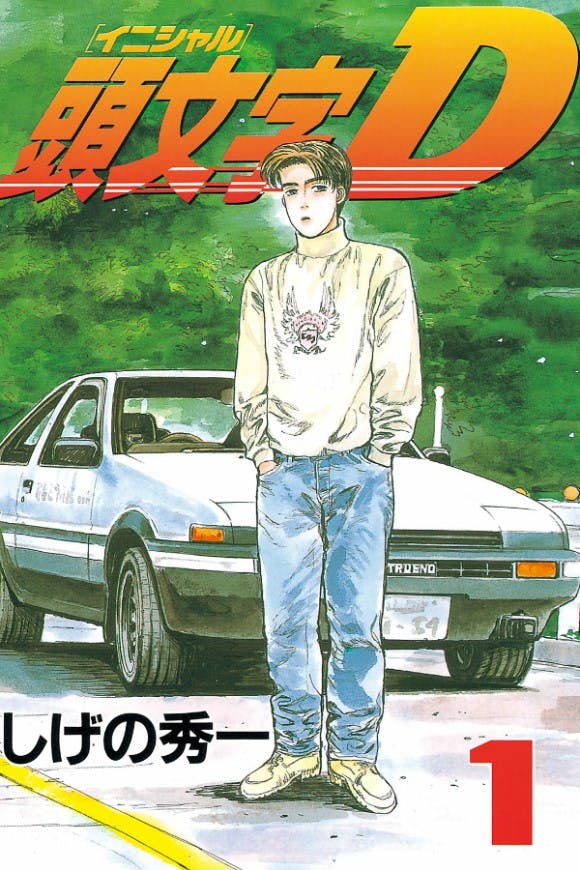

Japanese marques only received secondary attention in The Circuit Wolf, and that’s not entirely surprising. Toyota’s 2000GT was short-lived, and Nissan’s Fairlady Z had only recently proven that Japan could build globally-competitive sports cars. Having seen how keen the country was for performance cars in the 1970s even if an oil crisis hindered sales, in the 1980s Japanese manufacturers unleashed a flurry of vehicles designed to meet every consumer’s sporting desires. Regardless of whether it was an entry-level AE86 Sprinter Trueno or a high-tech Skyline GT-R, those kids of the ‘70’s were first in line to buy them.

Meanwhile, from the ‘80s through the 2000s, other manga like Over Rev!, Capeta, Wangan Midnight, and the well-known Initial D carried on the pop culture tradition of The Circuit Wolf, but this time with a focus on Japanese cars as well. Now exporting the special rides, Initial D in particular would help build Japanese-market sports car mythology on American shores.

Even though by all accounts the supercar boom died out around 1979, the passion for racing ignited in many by The Circuit Wolf never truly left the hearts of Japanese car enthusiasts. It was only a few short years before Honda rejoined Formula 1 in 1983, and F1 returned to Japanese shores at Suzuka in 1987. Japanese motorsports fans now had outlets for their excitement, and over 30 years later there’s no sign they’re letting up. It’s no wonder F1 drivers rate Japan as one of their favorite stops.

Like Japanese F1 fans returning to Suzuka, those Ferraris that coursed manga pages and stadiums across Japan in the ‘70s made their presence felt a decade later. As the Japanese economy took off in the 1980s, the soft spot for European exotics created by The Circuit Wolf still lingered. Of course, the school kids from the late ‘70’s would still have been too young to afford such a car at that point—the Ferrari bubble was being fueled worldwide, especially in America and Japan, by wealthy enthusiasts and then by speculators. Once the bubble burst and prices receded in the mid-1990s, those kids who once drove their Ferrari erasers across a school desk now had a chance to buy a real one of their own. The supercar boom had come full circle.

Shinichi Ekko is a journalist, automotive historian, consultant, and founder of Maserati Club of Japan.