Welcome to Sebring, where the race is secondary to the party

Famed CBS anchorman Walter Cronkite earned the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1981. Apparently, they awarded Cronkite for his journalism career, and not for being a commentator at Sebring International Raceway–a 17-turn race course located among acres of orange trees in Central Florida. It’s entirely possible that Cronkite, the Official Voice of Sebring, was on the microphone–and possibly even witnessed–one of the more zany events that occurred in Sebring’s temporary party square Green Park.

According to a story in the Tampa Bay Times, the culprit “got epically drunk on Chianti at the all-day car races in Sebring, crawled around in a white fake fur coat like a polar bear covered in dirt and tried to launch himself onto the track. Friends grabbed his ankles.” The suspect was original Florida Man Jim Morrison, the eventual lead singer of The Doors. Green Park–which is neither particularly green nor much of a park–serves as the annual location for motorsport’s little Woodstock. Antics like Morrison’s are commonplace. (Animal Hill at the now-shuttered Bryar Motorsport Park in New Hampshire may have been the only place in America to rival Green Park’s festivities.)

Fast forward to 2022, and I was on-hand to experience the Park. Oh, and to watch the annual Mobil 1 Twelve Hours of Sebring. It’s one of the most famous sports car endurance races this side of the Atlantic and sanctioned by International Motor Sports Association (IMSA). This year marked the 70th running of the prestigious event. Drivers took the green flag on Saturday, one day after the World Endurance Championship’s 1,000 Miles of Sebring– which should have been accomplished in the allotted eight hours, but instead logged only 754 miles due to caution flags and a lengthy red for a particularly nasty accident involving an upside-down Toyota.

Green Park is tamer now. Perhaps, legend has outgrown real life. That said, it’s still not docile by any definition. Every year race fans bring seedy lounging furniture from home. Rather than take it back, they set fire to the dirty sofas. Not to say there weren’t any, but I couldn’t locate a single smoldering sofa after Saturday’s race, which always ends at 10:10 p.m. That’s typically when the party shifts into high gear. Still, I’m sure many still-hungover attendees told Sebring sofa stories at work, on Monday.

Since NASCAR purchased the track, it no longer releases attendance figures. Few crowds have appeared larger than the 169,000 fans who swarmed Sebring in 2006. This year felt big, though. Very big.

While Green Park is certainly the party epicenter, much of Sebring’s personality still spills into other areas. The wandering Sebring Cows are always a welcome sight. These Holsteins are actually men and women dressed in black-and-white cow costumes, complete with udders, which can store any variety of liquids and be sprayed into cups or onto people. They’ve been strolling the grounds for 30 years, now, and live by the “Moo for a Brew” motto. They will pose for photos, but you’d better offer them a beer in return. They have udders and know how to use them. There are also the Drunk Monks: a faux-clergy-related group. I’m pretty sure Germany’s 24 Hours of Nürburgring is the only race that could rival a humid Sebring party, in terms of per capita cooler consumption. And those fans have 24 hours to drink. And do, incidentally.

The entire vibe at Sebring is unlike any other track. Even the course has character. It’s built on the 9,200-acre property of Hendricks Army Airfield, a World War II training base for B-17 and B-24 crews. Much of the base was paved in concrete, and much of that surviving concrete is used as a large part of the racetrack. It may be the bumpiest professional racetrack in the world, with no public or private support to smooth it out.

“Respect the bumps,” said Doug Fehan, who started Corvette Racing in 1999. Teams practice at Sebring during the off-season for longer endurance races. “If you can run 12 hours at Sebring,” Fehan said, “you can run 24 hours anywhere else.” Team Hardpoint Porsche driver Stefan Wilson said Saturday night that driving Sebring for 12 hours “is like wrestling a tiger in a cage. A tiger trying to kill you.”

Results–like the fans–have been interesting since the first Twelve Hours here in 1952, when a humble Frazer-Nash trounced the field. In 1974, when the race was cancelled as a symbolic nod to the gas crisis, 5,000 partying fans showed up anyway. A healthy roster of celebrities have raced at Sebring, including Gene Hackman, James Brolin, Lorenzo Lamas, Paul Newman, Steve McQueen, David Carradine and Patrick Dempsey.

Also, Walter Cronkite took a break from the microphone to race in 1959. On his first practice lap, Cronkite watched Edwin Lawrence crash a Maserati right in front of his Lancia. Lawrence did not survive. The newsman called the next of kin to offer condolences. Every year since, Lawrence’s family camps out at Turn 10 and holds a private memorial service. In fact, many of the legends that surround Sebring are tragic. In 1966, Canadian driver Bob McLean was killed when his Ford GT40 crashed and burned, surrounded by fans–who were not restrained by such novelties as guardrails. He was one of five fatalities that year. There was nothing much left of the car to tow away, so Sebring workers dug a big hole and shoveled it in. Somewhere on the track, the remains of a destroyed Alfa Romeo are buried.

Over the years, Sebring has provided drivers and fans with plenty of fond memories, too.

Rennie Bryant, owner of Redline BMW in Pompano Beach, first came to Sebring in 1970. “I was 15. My buddy’s dad drove us up. We slept in the back of a station wagon. Crowd-wise,” he said, “it’s totally different. Not nearly as rowdy.” Still, there was a modest bikini contest on an outdoor stage Friday night, which was interrupted by a deluge, and resumed in a tent. Reviews were mixed.

Randy Lanier, at his first Twelve Hours since 1986, said that Sebring was “off the chain.”

Lanier knows something about partying. He raced here five different times, and then became the Indianapolis 500 Rookie of the Year. Lanier lead an equally risky life off-track, as well. After his Indy debut, he was arrested for selling hundreds of tons of marijuana and sentenced to life without parole, during the Ronald Reagan administration. “A person should not have to serve the rest of his life in prison for selling marijuana,” he said at his sentencing. He was paroled in 2014. Now he lives in Florida, a state where most any adult who can scratch up $175 can get a seven-month license to buy marijuana legally. The irony is not lost on Lanier.

Speaking of law enforcement, who polices the Sebring party? (At least, the ones who weren’t chasing Randy Lanier.) “It was the Florida Highway Patrol Auxiliary,” Rennie Bryant said of the law enforcement back in the day. “If you weren’t actually killing somebody, you could do whatever you want.” Now, Sebring Police and Highlands County Sheriff’s Office squad cars are around every corner.

Still, Green Park after the Twelve Hours of Sebring is still…a little intimidating. First off, it’s dark, lit only by tiki torches and the wobbly lights of poorly-driven golf carts–which seems to be the preferred transportation of seemingly every spectator. At midnight, Green Park is inhabited by two types of people: 1) those holding a beer 2) those looking for a beer to hold. A golf cart passed by, hit a bump, and unbeknownst to the driver or its seven(!) passengers, a can of Coors Light rolled out of a cooler onto the grass. Three men dove for it. Marijuana smoke clung to the air, but no burning couch smoke. It was still early, though.

Beneath a large red and white circus tent, a band played on a foot-tall stage, barely visible behind the crowd. Men outnumber women at least five to one; unpleasant odds for any bachelor. The band–with a lead singer who needed to work on his high C–is playing Tears for Fear’s easy-listening “Everybody Wants to Rule the World.” Two hundred feet away, a repurposed, pastel school bus blasted John Lennon singing “Give Peace a Chance.”

Maybe Green Park isn’t Woodstock anymore.

“It’s still Sebring. It’s just different,” said Lanier, who attended Sebring International Raceway before–and after–his 26 years in government housing.

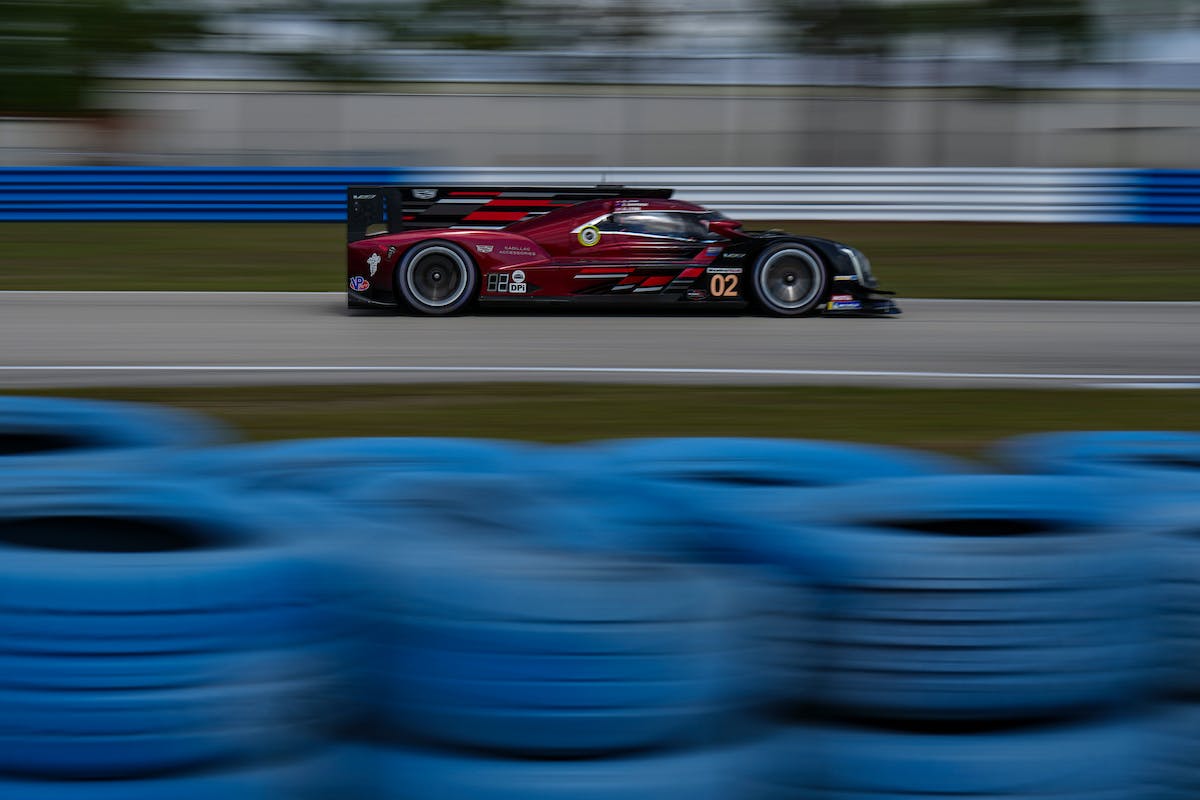

By the way, for the fourth time, Cadillac won the race. I almost forgot.