Jackson’s Ye Ole Carriage Shop honors Michigan’s upstart automakers

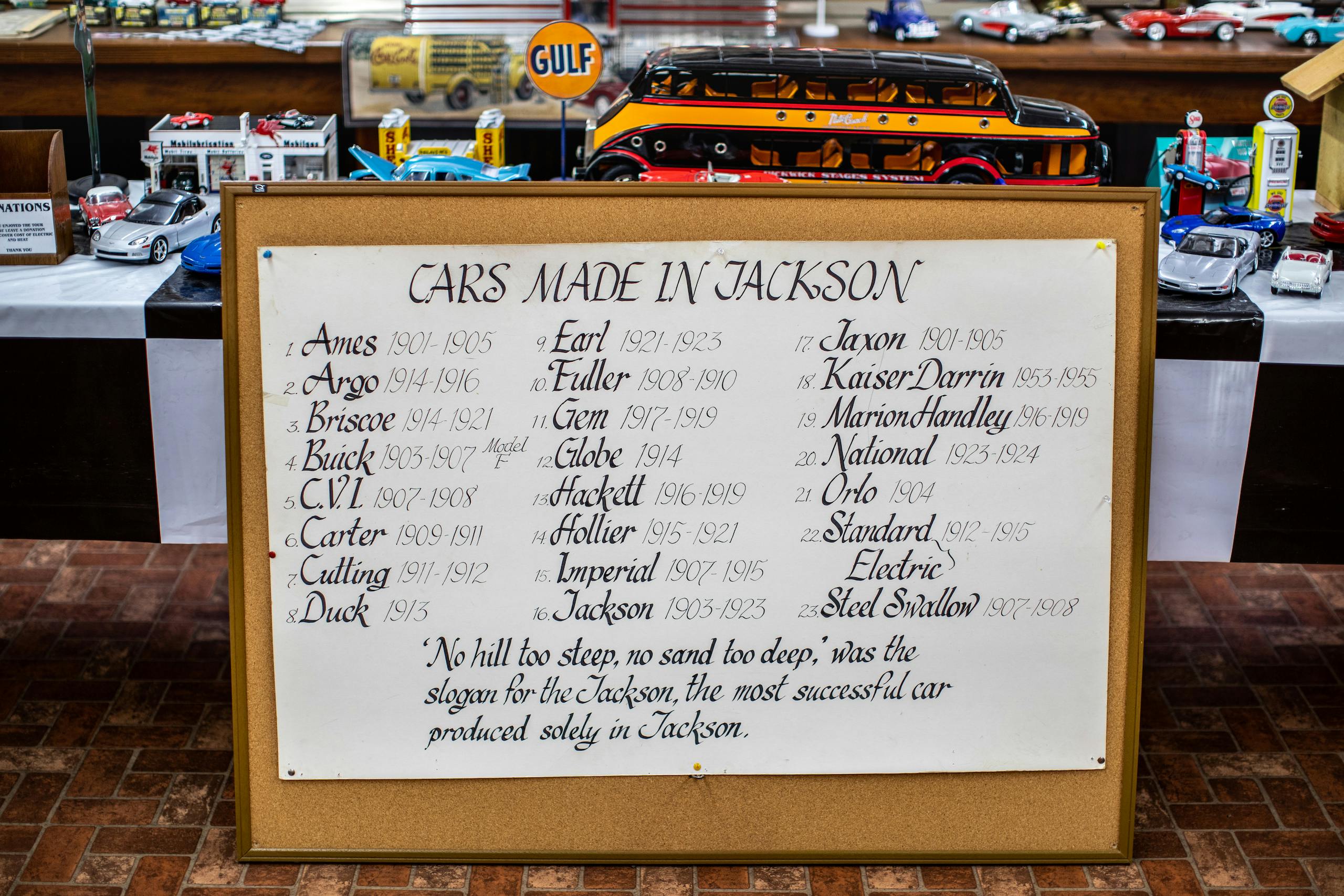

Detroit is a city synonymous with life on four wheels, but in the primordial years of auto manufacturing, another Michigan locale lay at the epicenter of auto manufacturing: Jackson. This was the early 1900s, an era of rapid industrialization and innovation. Twenty-two hopeful car companies opened up operations in Jackson before 1920—Ames, Briscoe, Carter, Cutting, Globe, Orlo, to name a few—but their names mean little today even to die-hard car buffs. Through a modern lens they might be regarded as ill-fated startups, assemblers of frivolous curios for the very wealthy. That virtually all of these early cars were built by hand is perhaps what doomed them, their creators hopelessly outgunned by the ruthless efficiency and profit engineered by Ford and its Model T in 1908. Nonetheless, there is a curiosity, vision, and ingenuity among these automakers that deserves attention.

Perhaps nobody takes that responsibility more seriously than Lloyd Ganton, the founder and proprietor of the Ye Ole Carriage Shop non-profit museum in Spring Arbor, Michigan, just outside of Jackson. Ganton was born and raised in Spring Arbor, and the museum’s treasure trove of 60 cars, automobilia, pedal cars, toys, and Coca-Cola memorabilia blossomed out of his personal collection. Restoration takes place at a small facility across the street from the museum, which is practically hidden in plain sight amid a residential neighborhood.

Ganton, the CEO and administrator of a retirement home, opened the facility more than three decades ago. There are now 19 cars in the museum that were built in Jackson—five of them “one-and-only” examples.

“I’ve been collecting pedal cars for 25 years only, mind you,” says Ganton, eyeing me with play suspicion behind yellow-tinted aviators. “Cars I’ve been collecting for 40.”

Ganton is a character, to put it mildly. Wonka-esque. Or perhaps a figure from the mind of David Lynch, tied supernaturally to his house of soda-pop and Tonka-toy kitsch. Now in his 80s, sharply dressed in a sport coat and slacks, he ambles around the seven rooms of the Carriage Shop at an easy pace. He speaks slowly, carefully, announcing each item of interest through a smile of childlike delight. His favorites come with a preface—for example, “This one will really put the frosting on your cake!”

Ganton’s opening glaze is the first car he added to his arsenal, a 1908 Fuller High Wheel. “High wheelers” were a style of car built prior to 1915, and with their large-diameter wooden wheels they evoke the horse-drawn carriages on which they are clearly based. The museum placard claims that the hand-cranked, chain-driven, gas-powered High Wheel, built in Jackson, is the only known 1908 Fuller to still exist. Ganton particularly appreciates the brass headlights, which provide 10 feet of illumination. He rescued the High Wheel from a barn on the other side of Jackson and restored it in 1972.

“From there I started collecting a few cars, and I would take them apart and put them back together just as a hobby,” Ganton says. By the mid ’70s he also had a Model T in the garage and connected with a guy in town who had a bunch of Jackson-built metal. Over time Ganton built up his collection, as well as his commitment to local history. His interests go way beyond prewar motorized carriages, too; the newest locally built car in the collection is a 1954 Kaiser-Darrin from the final year of Jackson production. From there the list spirals off into a reflection of Ganton’s eclectic tastes, with one room housing a 1960 Lincoln Continental, a 1950 Crosley, and an 1898 Goat Wagon manufactured—you guessed it—in Jackson.

Cars—or automobiles, as he calls them—have always been a part of Ganton’s life. And that life is inextricably tied to his hometown of Spring Arbor, where he sits on the township board of trustees and proclaims himself the unofficial mayor. Exact honorifics aside, he’s taking a unique approach to celebrating the town’s past. One room, in the process of being decorated for an upcoming Christmas party, is a faithful recreation of his mother-in-law’s kitchen circa 1955.

That interplay of personal and local history enriches the experience of visiting the Ye Ole Carriage Shop. Sharing floor space with the only known 1906 Steel Swallow—powered by a Harley two-cylinder—is Ganton’s first car: a 1947 Chevy. “I was 15. Paid $200 for it, earned mixing cement mud,” he recalls. A brief beat passes as his brain occupies that teenage memory. “Had my first date with a girl in that car. Now, don’t laugh, but I’ll let you think what you want about that!”

It’s about this time when Lloyd is called away on business. I am left in the capable hands of his eldest son, Troy Ganton, the museum’s assistant curator. He, too, was born in the area and lives about a mile from the museum. “Jackson was an interesting location for its car-building heyday,” he says. “Centrally located and home to lots of tinkerers from the heavy industry here at the time. It didn’t last because the cars were so low-production. And so expensive—one could cost as much as a farm.”

Not every brand with roots in Jackson went belly-up. Troy shows us to a 1907 Buick Model F, with a 22-hp two-cylinder OHV engine positioned inside an iron ladder frame. Buick made its first car in 1899 and opened its Jackson plant in 1905, but production ended at the end of 1907 when operations moved fully to the new Flint factory. The color scheme is wine with brass trim and white wheels—handsome here even in unrestored condition. “I convinced my dad to keep the original patina,” Troy explains.

Certainly this collection—these cars, the walls thick with signage and trinkets from years past—mean a lot to Troy, as well. There’s the 1903 Jaxon car that he helped haul back from Kansas in 1982, in the back of a truck. Or the years of connecting with other enthusiasts at Hershey, back when the swap meet took place entirely on dirt. “No asphalt, so at the end of the meet we’d all come together and push the motorhomes,” he says, chuckling. “These days Facebook just makes it even easier to connect around Jackson cars.”

It’s the Coca-Cola stuff, however, that seems to most capture Troy’s attention. He walks us through a room set up to look like an old-timey candy parlor, complete with a marble bar, little booths, and Coca-Cola everything from floor to ceiling. Troy pauses, reflecting on something. “I learned about collecting the hard way on Coca-Cola. You really have to study, stay away from the reproduction stuff,” he says. “Work at it and you learn. Over time it starts to come to you.”

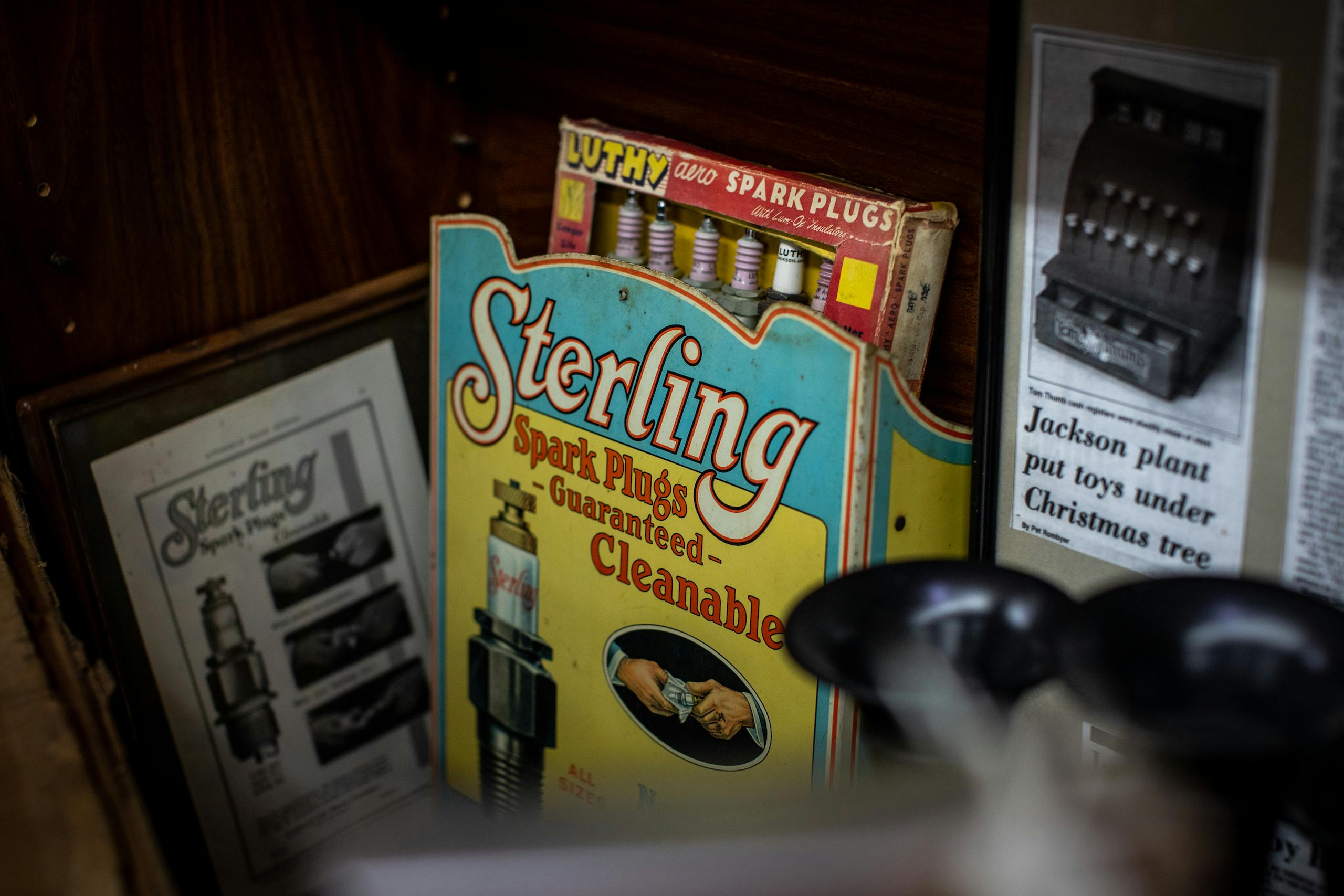

Just studying the contents of one corner of any one room in this place could fill an entire day. I burn a solid five minutes staring in awe at the variety of spark plugs nailed to a door, only to then be sucked into the study of a glass case of model fighter planes, followed by a registration plate that expired in 1908. I shout for Cameron Neveu, our photographer, to come check this stuff out, but he’s busy drooling at the shelves of Kodak box cameras.

Some of these collectibles have connections to Jackson. Whether it’s the Yard-Man snowblower, the Lockwood outboard row-boat motor, or a Tom Thumb tiny cash register, there is a huge variety of consumer and commercial items that were made in Jackson. One company, the Sparton Corporation, made everything from steel stampings to car cooling fan assemblies before it made its big break by developing an all-electric horn. After that came radios, of which the Ye Ole Carriage Shop has many.

Locals, visiting with the church groups or on a school field trip with their kids, remember some of these companies, Troy says. “They say they had a family member that worked there, and that’s the joy of it—when this stuff jogs their memory. What joy is any of it without that?”

The Carriage Shop is that special kind of place that you can go back to a dozen times and still feel like a kid. Where the smartphone never escapes your pocket, and you’re more than willing to be sucked down a rabbit hole of Vernor’s ginger-ale signage, license plates, and emblems from automakers long dead. There’s a moment, right after the door shuts behind you and your eyes readjust to the flat color of real life, that the whole experience seems like some kind of cozy hallucination. That’s the magic of the haven the Gantons have built, honoring the handiwork of generations of craftsmen and engineers. The Ye Ole Carriage Shop is a local legend in its own right.