CCV: When Chrysler (almost) made a 2CV

Make cars safer, cleaner and greener, and you make them more expensive. And at some point this butts heads with the necessary evil of profit margins: The difference between designing, engineering, developing and producing an Up and a Golf is minimal for VW’s bottom line, but it has to sell one at half the price of the other.

Today, even in Europe, the formula is making very small cars like the Up, Peugeot 108, and Smart Fortwo a dying breed. But 25 years ago, Chrysler was one of several manufacturers attempting to make small cars cheaper by building them smarter. And, inadvertently or otherwise, it created a kind of modern-day Citroën 2CV.

Called the Chrysler CCV, the name originally stood for China Concept Vehicle, a nod to its intended audience (in 1997, China’s automotive market was somewhat different from today’s technology-focused behemoth).

It was later re-dubbed Composite Concept Vehicle, but in either case one can read that acronym slowly and learn something: CCV. Two C… V. Even if you ignored its friendly face, arched and roll-back fabric roof and large wheelarches, it’s a cultural reference as subtle as dressing up in a striped sweater and a string of onions.

Under the CCV’s front-hinged hood sat an 800cc Briggs & Stratton V-twin (two cylinders being another 2CV cue), sending 25 hp to the front wheels via a four speed gearbox—controlled by a lever poking its way straight through the dashboard. Truly, an uncanny coincidence.

The 2CV wasn’t just a funny shape, though; almost everything on Citroën’s 1948 masterpiece was designed in the pursuit of simplicity. And so it was with the 1997 CCV, where the “Composite” portion of its name held a clue to the clever method of its construction. The car’s entire body was formed from recycled plastic.

Chrysler partnered with Cascade Engineering in Michigan on the project. You probably haven’t heard of them by name, but Americans have surely seen the company’s wares: they tend to be big, green, and hang out in dark alleys.

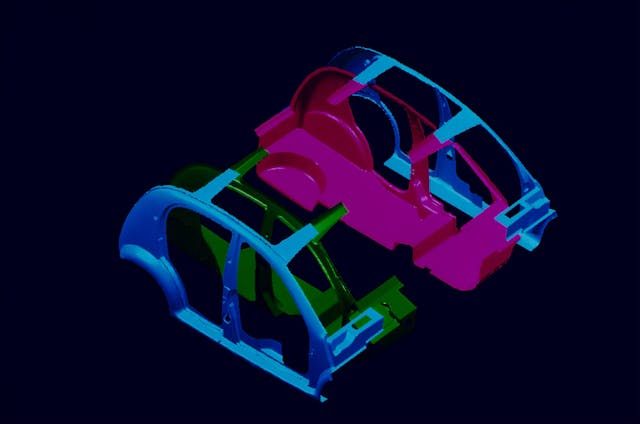

Injection-molded plastic dumpsters are everywhere in the U.S., and the CCV’s body was made using the same process, squeezing the equivalent of 2132 two-liter plastic drink bottles under 9900 tons of pressure to form four large body parts. These parts were then bonded together—a pair of outer panels, and a pair of inner panels that attach to them—and the finished structure (weighing just 95 kg, or 209 pounds) would then be bolted and glued onto a 2CV-style flat floorpan to receive its plastic doors, bumpers, and hood.

All told, Chrysler reckoned it’d take six or seven hours to build a CCV, against the 19 hours of the contemporary Neon. Some of that saving came from not requiring any paint—the injection-molded plastics were pre-colored, which not only saved time but eliminated the environmentally dubious, energy-intensive, and space-consuming paint shop process.

True to its inspiration, the CCV was economical in every sense: to produce, to repair (the body was springy and dent-resistant, but repair patches could essentially be melted into place and the damaged pieces recycled once more), and to run. Chrysler claimed 50 mpg (pretty decent in the 1990s), while a 1200-pound curb weight pretty much guaranteed low brake and tire wear. Economical to buy, too. Chrysler suggested a production model might come in at around $6000, a third that of a Neon.

Whether customers would have accepted something 2CV-basic in the late ‘90s is unclear, though the idea of a car with no airbags, no air conditioning, large slide-down windows and a 70-mph top speed was probably more palatable in a new car a quarter-century ago than it sounds today.

Ultimately Chrysler’s answer to the tin snail reached a line of salt, despite its cost advantages. It’s likely, given the construction, that crash testing proved a somewhat literal barrier, while cheap cars in emerging markets were already more sophisticated in many ways. As automotive giant Tata found out with the absurdly cheap Nano, even buyers trading up from a moped don’t want to be seen in something so overtly austere.

There’s depressing irony in the way regulations designed to make cars safer and more environmentally friendly are killing off those that have the least holistic impact. The cars that are most affordable tend to cause the least damage when they hit something, are lightest on resources, and take up the least space on the roads.

The world wouldn’t necessarily be a better place if it was full of cars like the Chrysler CCV—though it might be a somewhat jollier one—but the project demonstrated that smaller, more affordable cars were still possible if designers and engineers simply took inspiration from the right places.