Salt, sweat, dirt, and tears: Four life lessons I’ve learned from motorsports

Another week on the Bonneville salt with no record to show. It’s just one of the realities of land-speed racing that is forgotten during the celebrations when barriers are finally shattered. After the fire at World of Speed, the Knapp Streamliner team and I returned last week for the SCTA World Finals only to fight a string of suspension- and transmission-related issues. We simply never got a clean pass. Despite this, we still had a great time while making incremental progress on each run, winning the small battles.

As in all of motorsports, failure must be faced—even if, in the time-trial formats of land-speed racing, failure isn’t strictly defined as losing to a competitor. Returning home with no record to show for our tears and sweat, I still knew exactly how—and why—guys like Burt Munroe built their walls of broken speed parts dedicated to the God of Speed. On the drive back home, I found myself pondering lessons that motorsports has taught me—after triumph, sure, but more often in tragedy.

The right solution isn’t found without failure

If you asked Kenny Duttweiler how many of his engines he’s seen shattered in the pursuit of speed, he probably wouldn’t be able to finish counting. If you talk to someone with 50 years of experience building engines who claims they haven’t scattered and torched their share of hardware, they’re either lying or simply never pushing an envelope worth mentioning. Duttweiler, on the flip side, dabbles in designing engines for which there are no known recipes, his parameters outlined by the goal of building the world’s fastest piston-driven car.

Endurance engines sacrifice output for durability, and most drag-racing combos are looking for the ragged edge if it means a fraction of an extra horsepower. Land-speed racing, on the other hand, demands immense power sustained over a long period of time. No other racing discipline requires as much continuous full-throttle time. In this unique mechanical environment, an understanding of what’s required to achieve a record often coincides with a grasp of the limits of currents parts technology. Land-speed racers churn out horsepower numbers that would make everything short of a Nitro car blush—for periods of time that would exhaust Le Mans racers (even without today’s neutered Mulsanne Straight).

Even with such an intimidating brief, it’s in failure that minds like Duttweiler’s thrive. Defeat generates a new problem to solve, which afterwards nudges the bar of performance a little higher. Land-speed racing is particularly prone to such a pragmatic approach, because there’s never any prize money for a record. The rules preserve the machine as the most important factor to earning a spot in the history books, and history has proven that reaching for the absolute edge of performance, a title will not come easily.

The mentality around failure is complicated. For many, any flavor of failure is a personal defeat. It’s not the goal, it’s not the win you’re building towards with endless long nights and strangled budgets. That cost, spiritual and literal, defines the trajectory of anyone in motorsport. Psychology papers expound upon the obvious, but we often tie our sense of self-worth and capability to the results of our actions, and the experience of falling short on a goal hits hard. The feeling of defeat is so strong that it can push otherwise motivated individuals to avoid it like the plague, refusing to approach or study these barriers because the cost of breaking through them is simply too high.

That element of human ego is one that motorsports hammers and forges over time. Those who adapt well to this smelting process learn to turn those “what-if” thoughts into future tools of success rather than self-sabotaging reminders of the past. Even when the failure is entirely your fault, the choice is to either sit in self-blame or simply take it as a hard reminder moving forward to adjust habits. Blaming the machine when parts fail provides a cathartic release, sure; but only though a careful understanding of the mechanical failure can a machine be pushed to its full potential. Technology only advances when we exploit it beyond the original design limits, find new problems, and selflessly push to solutions.

The joke on the salt last week was that every run was a “prototype run.” You rarely know you’re earning the run until it happens, and every push off the start line was just one more blind step towards success. Duttweiler said it best to Hot Rod Magazine in 2017: “When I flip that page in a book, I’m not going back to that page. We’ve already been through that and we can’t change it. But if we’re working on something for tomorrow, we might be able to change that.” The ability to move forward after a failure with a little extra wisdom is vital in motorsport.

Without struggle, success can be forgettable

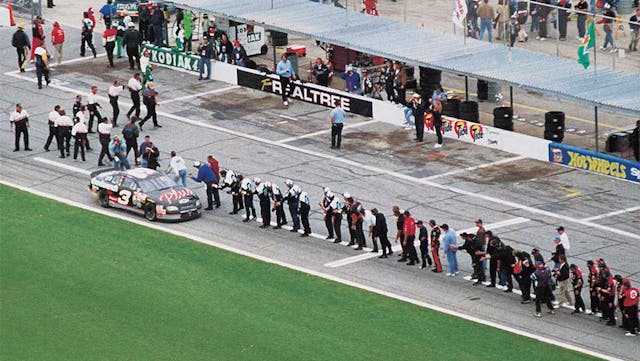

Easy wins fill our daydreams for a reason. It’d be nice if just for once the machine worked perfectly, needed no adjustments, and did its “job.” If the weather would comply and give us a clean run. If that one guy weren’t an a**hole driver/official/whomever. Everyone who’s pushed a wheel into competition in one way or another knows that a single moment can break the plan and render the outcome uncertain despite every effort. Dale Earnhardt, Sr. is today known as a racer who simply won on NASCAR ovals—or fight you trying. His legendary tenacity has outlived the misfortune of his passing, but for Earnhardt, the first driver to tie Richard Petty for the most Cup Series Championships, success was encapsulated in moments like his 1998 win at the Daytona 500. A man like him isn’t brought to tears over nothing.

For two decades, a win at the Super Bowl of NASCAR eluded the Intimidator’s grasp. The 2.5-mile tri-oval was his albatross, and his 1998 victory came after 19 consecutive attempts, four of them resulting as runner-up even during his best years in the early- to mid-1990s while racking up those seven championship wins. Freak accidents were often waiting for Earnhardt Sr., like the leftover piece of Rick Wilson’s broken bellhousing from an earlier wreck that cost him a tire on the last lap in 1990. Or, more famously, the seagull that battered his attempt the following year, colliding with the #3 car on the second lap and blocking its grille. Despite clawing back to second place after losing time to removing the wayward bird, Earnhardt got loose in the last lap and spun backward before meeting Kyle Petty head-on. In ’86, he’d even ran out of fuel with three laps remaining.

“I don’t think I really cried as much as my eyes watered up that last lap coming to get the checkered. This is pretty awesome because we worked so hard to win this race,” he admitted in 1998 to the Las Vegas Sun after finally clearing house that Sunday. “I was overcome, to say the least… We’ve lost it every which way you could do it, and now we’ve won it and I don’t care how we won it, we won it.”

Though his death at the 2001 Daytona 500 defined much of Earnhardt Sr.’s legacy, it was the twenty years of struggle leading to his ’98 victory that cemented his legendary place in NASCAR history. The 500 has been on the schedule since 1959, its winners circle claimed by many—sometimes multiple times over by NASCAR’s greatest—but we remember few repeat Daytona victories like we do Earnhardt’s single claim to the crown. He wrote the kind of relatable allegory that fueled the peak years of NASCAR Cup Racing during the 20th century.

A respect for, but not fear of, the risk of death

The 2012 Pikes Peak International Hill Climb was formative for many reasons, but it was watching a friend of mine slide off the hill that most altered my view of the sport. It’s one thing to catch a big wreck on TV, or to be a grandstand witness to the collisions of drivers who feel familiar, but the first time you experience a horrific racing accident is one that defines the sport to most individuals.

Yuri Kouznetsov, codriver of the Mitsubishi Evolution that crashed near Devil’s Playground, was a friend of mine from the rallycross series that had more or less opened the door to my attending at Pikes Peak that first year. We had all become fast friends in Texas, and for a handful of us to be at Pikes Peak together was just the top of the world as a burgeoning racing family that year. It had been a storybook year for our team, all things considered. Practice had gone smoothly and race day was the icing on the cake, with a decent slot in the day for our run. We had a skeleton team on the start line, since the car didn’t need any real babysitting, and we parked ourselves around the hillside below Devil’s Playground to get a good view of everyone winding up through the W’s from Glen Cove. Where I stood on the inside of a corner, drivers would dip out of view for a few moments before revealing themselves from behind the switchbacks for a blind left-hander. The turn was fast, with a sharply decreasing radius, and we later learned that driver Jeremy Foley had overdriven the corner under power for much too long before realizing his mistake. The Evo came into view from behind the cliff side for a brief second before it slipped off the road and into the abyss of a blue sky. From our vantage point, they had fallen off the mountain with nothing below to catch them, and for the next few moments, I wasn’t sure if I had just watched a friend—or two—die.

By the time the car came to a rest, it had fallen about 500 feet. With Foley and Kouznetsov’s wives on the hillside with us that day, and having already witnessed the breakdowns in digital communication on the mountain during incidents, I decided to make my way directly to the car. I figured, too, that a friendly face wouldn’t hurt two drivers who’d just stared down death. Both driver and codriver had managed to crawl out of the car as I began to scramble down, and I met them just moments after safety crews had rappelled down from the road way. Foley had been cleared on site, but Kouznetsov’s cracked helmet and dislocated shoulder sent him downhill in a Life Flight ‘copter despite his displaying good signs of only minor injuries.

I had already read works like David Freiburger’s The Importance of Risk, and had just begun to dig through the introduction of Neil Robert’s book, Think Fast, which expands upon the idea that other significant individuals in your life must also accept the chance that the choice to race may be the choice to die. But watching and reacting to a situation firsthand gave me a new respect for the consequences involved. The outcome lies not only in the risks taken by a driver in the heat of race day, but in the decisions a tuner or crew makes for their driver, too—safety is paramount. Failure is still a path to learning, but some failures put lives at risk, and the decision-making process from the moment a race is committed to must reflect that in a form of respect instead of fear.

As Jay Meagher poignantly said about his path to the SCTA 300 MPH club at Bonneville: “Well, if this is gonna go sideways, this is gonna go sideways. If this is going to end badly, it’ll end badly. I still have to choose to experience things in life without being terrified of them.”

The Racing Family persists

Okay, sure, Vin Diesel has memed the idea to death—but the reality is that many racing events bring together like-minded people from all over the globe, and with that comes a unique friendship. Especially given the pride that comes with success and the personal cost of failure that hangs perpetually in the balance, fast friends often become best friends who understand from experience many of these lessons mentioned so far. Despite being competitive, racing is a call to arms for people who’d otherwise likely never cross paths. An event can shrink the world into a bubble in a way that becomes irreplaceable in everyday life. At least once a year, a race or trial or weekend can be a chance to see and work with some of your favorite people. Certain disciplines of motorsports require a specific type of personality to succeed, too—such as modern-day Drag and Drive events.

For these events, racers built drag cars to survive over 1000 miles of street driving in the course of five days of racing. While many headlines come from the more insane builds, like the ’13 Camaro ZL1 of Tom McGilton, the bulk of the attendees build their cars in their garages over the span of many years, whittling away at their perfect street car the same way that James Taylor and Dennis Wilson did in Two-Lane Blacktop. For many, these events represent saved-up vacation hours, hours of overtime and weekends of side work to stock their racing budgets. The determination to make those life choices behind the scenes—while possessing the skills and perseverance to succeed in what’s essentially a cross-country, barn-storming endurance race—builds a character profile of sorts. Given the combination of a time-trail format and the survival mentality needed to push an often-ailing machine through the slog, the community centers on mutual respect through the act of participation. Racers loan each other spare parts, time, or tools with the idea that they’d rather settle their success on the track. More well-known facets of drag racing get heated: Competitors go through great lengths to game their opponent, where the community is adversarial and just, frankly, no fun to be around, because everyone is just there for a paycheck. By shedding that armor, events like Drag Week and Rocky Mountain Race Week have built an environment akin to nothing else in the sport of drag racing.

In the photo above are three cars: the Fox-body Mustang belongs to Tim Flanders of Ohio, the Cutlass to Nick Mancini of Long Island, and the Pennsylvanian-built Chevelle Malibu to Rick and Jackie Steinke. Their codrivers too, are from equally distant lands. They escape the monotony and stress of life for a week of chasing time slips across the country, push themselves as much as their hand-built machines, and grow a unique bond that defines a racing family. If not for one of these hell weeks, they’d never get to know and rely on each other, and even while apart during the rest of the year, they’ll still find ways to butt heads on a track, look out for each other though rough times, or run hard to find parts across the country. Finding good people in the car community can be tough, but given the right circumstances, some events attract the best of them.