Revived after 64 years, 1927 Nash enchants the Wisconsin town it never left

Thousands of years ago, during the last ice age, retreating glaciers leveled the American Midwest. Left behind was a mix of silt, clay, boulders, and crushed gravel collectively known as “drift.” A pocket in what’s now southwest Wisconsin was spared this violent reformation. Geologists refer to this as the Driftless Area—an emerald landscape with swells of rolling hills, trout-filled streams, and hardwood forests. Soft bedrock means many caves and sinkholes that are home to special ecosystems. The beauty here runs deep.

I exit U.S. 151 at the crest of a gentle slope that wends its way down toward the northeast corner of a historic but nevertheless fairly typical-seeming Midwest town. Mineral Point, population: 2600. Here on the outskirts of town, the first tendrils of summer morning sun stretch out over farmland, bringing warmth. Crops flit back and forth in the breeze under cotton-ball clouds that float, listless, across a dome of blue. It’s a scene worthy of a postcard, but something rather extraordinary waits for me in Mineral Point. A long-hidden automotive jewel, recently unearthed.

Homegrown local David Engels reached out and convinced me to travel from Michigan to see it for myself—a 1927 Nash Light Six sold new at his grandfather’s brick-faced dealership in downtown Mineral Point. Much work has gone into making the car ready for a triumphant return to the town’s 2021 Fourth of July parade down High Street, where it last ran in 1957 before parking in a nearby barn. There it would rest, between wood rafters and dirt floor, for more than sixty years.

One of several prominent towns to spring up in the early years of the Wisconsin Territory, Mineral Point became the seat of Iowa County in 1829. The Driftless Area was teeming with untapped resources, and industrious prospectors flocked there to mine the rich deposits of lead ore. Native Americans long knew it as a land rich with minerals and traded with the French for fur in the 1600s. At the end of the 19th century miners discovered zinc at the bottom of the exhausted lead mines, and by 1891 Mineral Point was home to the largest producer of zinc oxide in the world.

With industry came the automobile. Wisconsin’s own Nash Motors, headquartered 150 miles east in Kenosha and led by former GM president Charles W. Nash, was founded in 1916. The brand won early success with the rugged four-wheel-drive Quad and was one of the first domestic automakers to embrace overhead-valve engines, largely similar to those of Buick, from whom Nash poached chief engineer Nils Wahlberg. By the 1920s Nash had become an underdog success story. It earned esteem for its constant advancement, packing its cars with fresh technology while keeping prices attainable.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

Engels’ grandfather set up his Nash dealership and service garage, J.E. Engels Auto, in 1920. He was a friend and former employee of “Charlie” Nash, having worked as a quality assurance inspector at one of the businessman’s foundries. In 1927 Engels sold one of Nash’s newest models—the Light Six sedan—to a young woman named Emma Benson, the dealership’s own bookkeeper. The Light Six was Nash’s entry-level offering, renamed that year after the company scrapped plans to fold in the value-oriented Ajax brand. It was a sophisticated design for its time; the 170 cubic-inch flathead straight-six boasted seven main bearings, pressure-feed lubrication, and 40 hp at 2400 rpm. That was competitive performance with the new-for-’27 Ford Model A, though at $995 new the Nash cost roughly twice as much.

The Nash greets me in the driveway when I arrive. The dark green paint and black running boards are obviously worn, as you’d expect for a car that had been sitting in a barn since the Eisenhower administration, and the resulting patina oozes old-world charm. Engels walks into view through an open garage door, already scouring his soiled hands with a fresh rag so he can shake my hand. He smiles—the big kind you have to engage your whole face to pull off. It comes to him easily.

“Ready to meet Emma?” he asks. “Couldn’t be a better day for it.”

***

When David Engels first called me, more than a year before July 2021, he promised a barn find that would “make your pulse race and your blood run cold.” As Engels shows me around the Nash, which he’s lovingly named after its original owner, he also walks me around the garage where he’s been storing it. The big Nash sign against the back wall is actually from the J.E. Engels dealership, which his family sold almost forty years ago. Automobilia, Nash and otherwise, dots the walls alongside black-and-white pictures of his grandfather, who was also an inventor. Framed in a prominent spot is a copy of a patent he gained for a tractor hand safety brake.

In one photo, on the side of a brick building, I recognize the Nash sign from the garage wall. Standing next to one of the cars in the foreground is a young woman. “That’s Emma Benson,” he says proudly. David’s mini museum of his family’s legacy, rooted in Mineral Point, does the Nash justice. We stand there in silence for several moments, letting the history waft in the air around us.

A handful of his friends soon appear to see the Light Six off. First on the scene is Sam Palzkill, a key player in Emma’s reemergence.

“The original Emma, Emma Benson, was my aunt,” he says. Sam is soft spoken, friendly, and careful with his words. “She was a nice lady, born in 1905. No kids, and my brother and I were her only nephews. We used to bring her eggs from the grocery store.”

Emma lived outside of town on the Benson family farm on Highway 39. The operation was small in those days—crops and a few cattle for beef or dairy, Sam tells me.

“I must have heard the story a thousand times about the day her and her dad went into town to buy the car,” he says. “David’s grandfather sold it to my grandfather and put it in her name. She used it to get to work, to run errands. Her diary talks about Emma and her sister being very active socially, so the car really got around.”

Around Mineral Point, that is. In the thirty years between when it was sold new at J.E. Engels and the Fourth of July in 1957 when Emma parked it in her barn, after the parade, Sam reckons the Nash never left town.

Emma died in 1986, at the age of 81. Her estate fell to Sam’s brother, who had no interest in selling the car, so the Nash did little except sink deeper into the ground. When he passed away in 2019, the Nash was thrust into Sam’s care.

“I called David because of our families’ connection. I knew he wouldn’t junk it, or anything. I still have the title, a funny little piece of paper.”

When David found out Emma’s Nash was still there, a mere three miles from his house all this time, he could scarcely believe it. Driftless Area, indeed.

Excavating it yielded even more discoveries. Not only was the Light Six intact, but the dryness of the dirt floor had also kept the undercarriage from accumulating any significant moisture. A cursory search of the barn revealed the original radiator cap, floor jack, lug wrench, tire chains, and hand crank. The original headlights, running lights, dash lights, and horn still worked.

“At that point,” David explains, “I was all in and bought it from the estate. We cleaned it up, washed it, and vacuumed up who knows how many walnut shells. Preserving the history was always our top priority, but the car isn’t for me. Our end goal has always been to find Emma the forever home she deserves.”

The Light Six didn’t run, of course, and neither David nor Sam had the expertise to fix it. Who even knows how to get parts for 1927 Nash, let alone install them? This being Wisconsin, an expert Nash mechanic lived just 60 miles away in Soldiers Grove. Guy by the name of Jim Dworschack, founder of the Nash Car Club. Those who knew of him were skeptical he’d agree to work on the car, though.

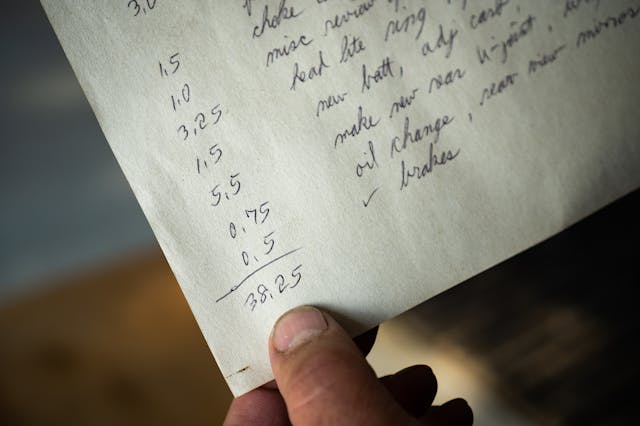

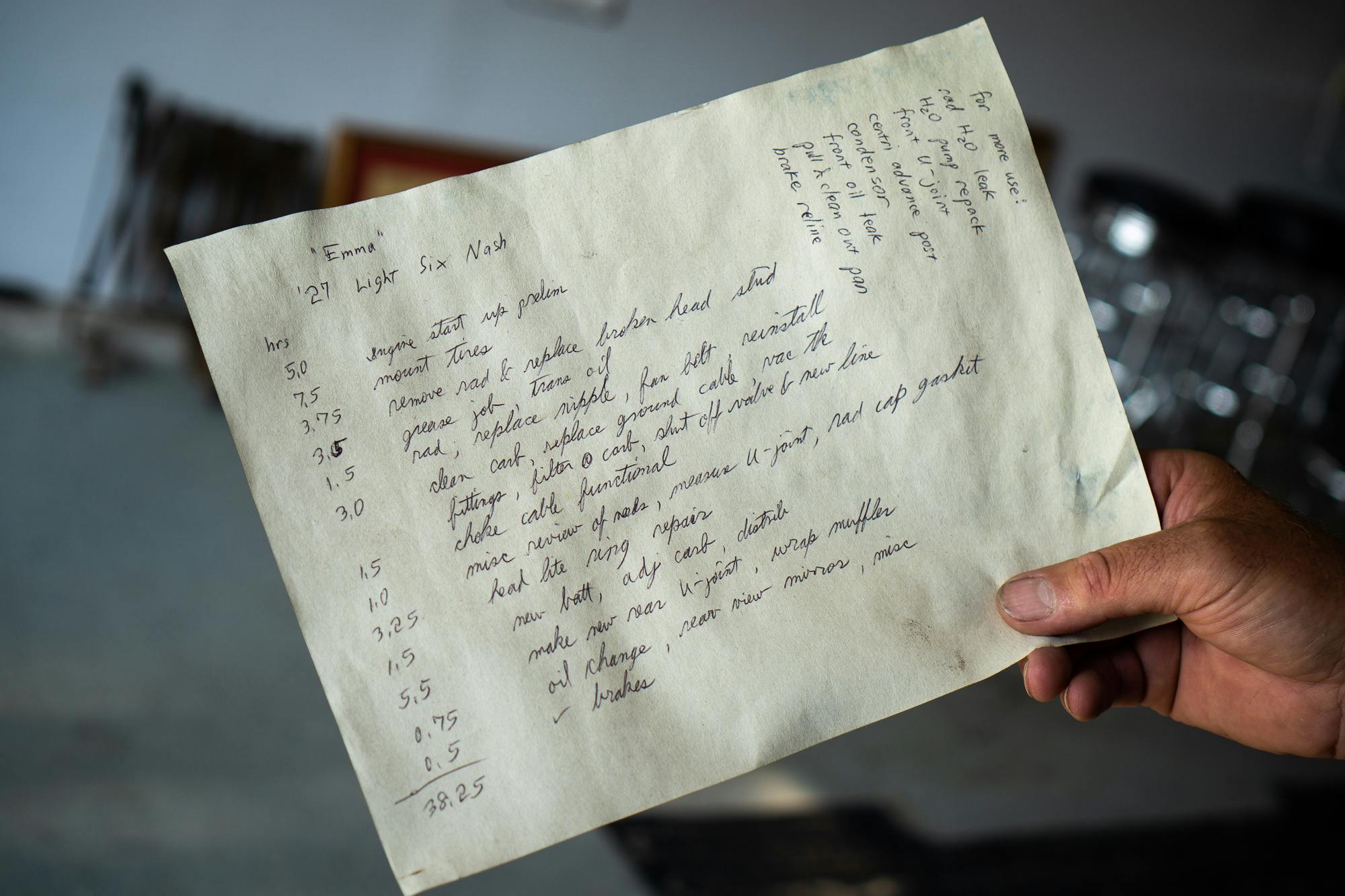

To David and Sam’s delight, the doubters were wrong. Jim was astounded at the find and put Emma at the front of his work list so he could have the car ready for next year’s parade. The first time he started the engine it ran pretty well for about 15 seconds. The second time it died abruptly and without warning after a mouse McMansion inside the flywheel clutch cover got caught on the starter. That was the worst of it, though. Jim says the work took nearly all of twelve months. The Nash’s repair list included basics like a battery, brakes, and oil along with everything from roof repair to a new u-joint, radiator cap gasket, carburetor, choke cable, and a wrap for the original muffler. Jim’s hand-written invoice—the guy doesn’t have a cell phone—indicates just 38 hours invested. David knows that’s well below the real figure.

“Like me, Jim knew that Emma’s story wasn’t over,” he says.

***

We don’t have to be at the parade for little while, but David, Sam, and a few of their friends are way too excited to sit still. Their wives have started the festivities early as they descend on the driveway dressed as Roaring Twenties flappers, period music pumping from a speaker in the back seat of the Nash. They all insist I take Emma out for a test drive before her parade run.

“I taught my 17-year old daughter how to drive this car,” David says, handing me the key. He stares down at me through the eyeglasses perched on his nose. “Your turn.”

The flathead fires right up, six cylinders coughing to attention before settling into a steady, rhythmic chugga chugga. David’s in the passenger seat beside me, practically giggling. The clutch feels easy, forgiving. There are three forward gears spaced about a mile apart, which yields long throws for the wood-knobbed shift lever. Gentle pressure on the throttle delivers a healthy, sudden response from the inline-six, but I quickly get used to it and find the relaxed inputs the Nash prefers. We cruise about a mile down David’s street and turn onto a main road toward town. I don’t have much time in prewar cars, so the whole experience is new to me. In a lot of ways, the Nash feels like a more refined tractor with a roof and two rows of seats. It’s honest, and I like it.

How many times has this car traversed these roads? Sucked in this air?

Before I can ponder those questions for more than a few moments, the engine starts losing power. Uh-oh. What did I do wrong? The car dies on our way down a hill, so I use the momentum to coast us safely onto the shoulder of a side street. The parade starts in about an hour.

“Don’t worry, she just up and died. You drove fine,” David assures me. There isn’t a trace of concern or urgency in his voice. “We’ll get her fixed up in time. And if we don’t we’ll just tow her to the top of High Street and roll on down the parade in neutral!”

Two of David’s buddies, Chris and Todd, are soon on the scene with a basic tool kit, some crimps, splices, and a voltmeter. The gradual loss of power and lack of any other mechanical noises suggest an electrical failure, which it turns out is Chris’ specialty. “Oh yeah,” I ask. “What do you do for a living?” He doesn’t miss a beat. “Electrical engineer for high-voltage power systems. Bit of everything, though. This and that.”

Emma’s six-volt electrical system is no more complex than a ham sandwich, and Chris tracks down the problem in no time. An old wire between the battery and the starter switch has burned through. A few minutes later he thinks he’s fixed the issue with a rudimentary bypass—good enough to last the day, until a proper repair can take place. We start the car, fingers crossed, and the flathead leaps to life as if it knew we had somewhere important to be. “Emmaaaa!!” David shouts, both hands raised over his head.

We hit the road newly energized and drive back to the house for a celebratory beverage. David and Chris change into their ’20s outfits before heading to the parade. The final touch: Old Glory fixed to the back of Emma, so the stars and stripes can blow in her wake. The flag looks old, I mention to David. “Probably is,” he says. “A few weeks ago, we found it hiding on the top floor of my grandfather’s old dealership downtown.”

It’s time.

***

High Street is a madhouse. The sidewalks are packed with people already enjoying the day. Older folks smart enough to have claimed their spot early have found some shade. Plenty of others are happy to soak in a bit of sun, either standing against the shopfronts or posting up right on the curb. Making the most of the closed-off street before the parade begins, kids play and chase one another, still a couple of months away from report cards and homework.

The parade begins to great fanfare. Entrants are numerous and diverse—police and fire department, local businesses, veterans, and a nice share of classic cars. None can hold a candle to Emma. The car trots by with David at the wheel and two dancing flappers stationed on the running boards. Ragtime tunes fill the air. People are cheering, clapping, snapping pictures with their phones. They’re pointing at the sign on the side that reads: “This car was last driven July 4th, 1957.”

I overhear several people say that it’s the coolest thing they’ve ever seen at a Mineral Point Fourth of July Parade. If only they knew how this chunk of local history, thought lost to time, was unearthed by the descendants of the very people who brought it here.

Emma still needs a new home. David and Sam are patient, willing to wait for the right person and the right place. With any luck, she won’t drift far.

Nice article really enjoyed it.