Young blood gives new life to old Bugattis at Tula Precision

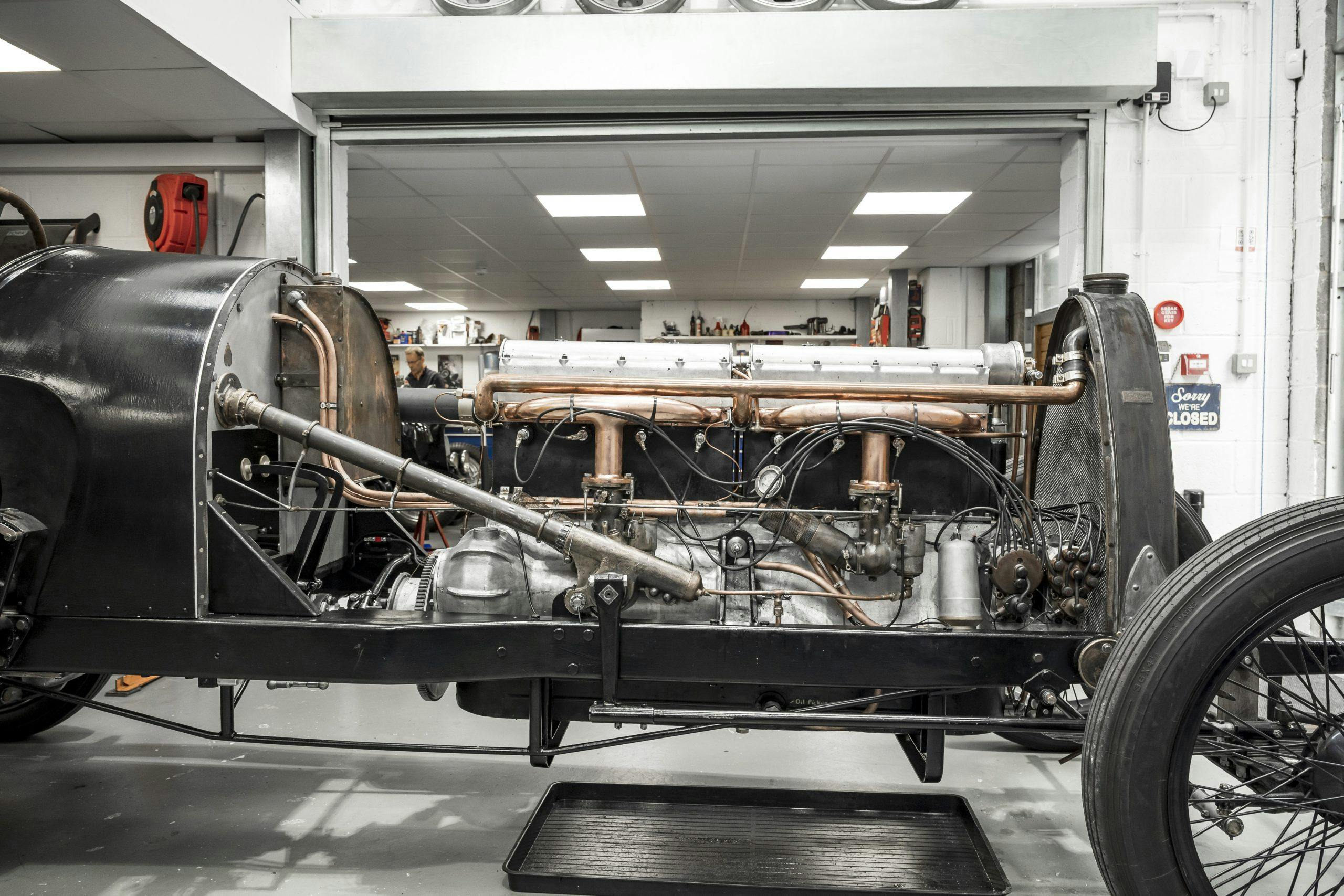

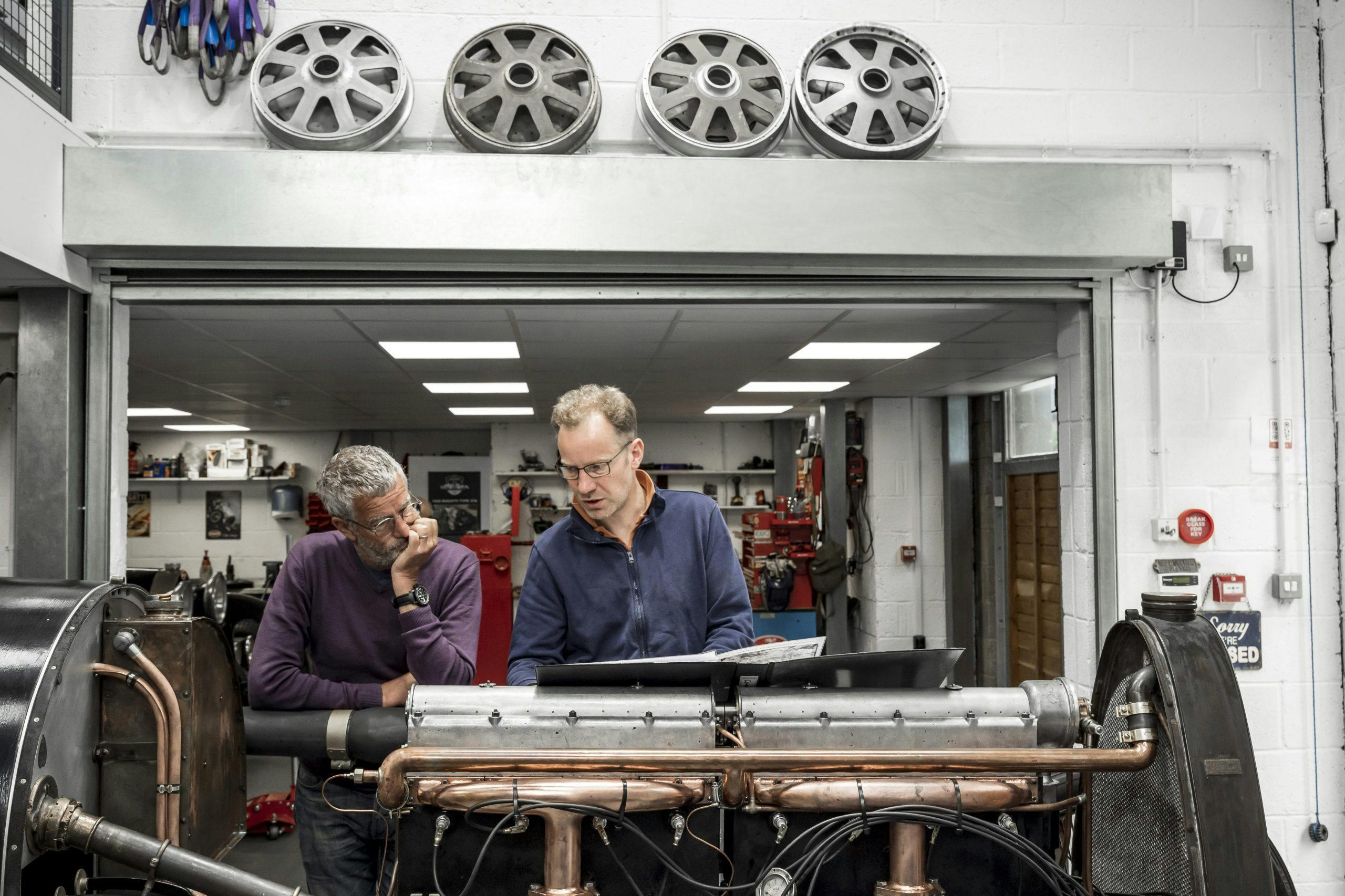

You don’t imagine for a moment that there might be disappointment when visiting a Bugatti specialist, but there’s a first for everything. It had been hoped that our visit would coincide with the firing up of the monstrous Bugatti Diatto Avio 8C but, unfortunately, during a trial run the day before a slight oil weep was spotted and Charles Knill-Jones quite sensibly would like to make further investigations before he and his team fire up the mighty 14.5-liter, eight-cylinder aero engine again. No matter, for there is plenty else to see inside the pristine workshops of Tula Precision, Bugatti specialists of world renown.

It didn’t start out that way and it wasn’t in the brief, but our Hard Craft series seems to have by chance turned into a celebration of youth in engineering. Our first subject, O’Rourke Coachtrimmers, is headed up by its eponymous owner who is yet to see his half century.

The Hard Craft series, including this installment, originally hails from Hagerty U.K., which you can visit here. It’s been expatriated to our site for your viewing pleasure. Do indulge Mr. Goodwin his native vocabulary.

By coincidence the proprietor of Tula Precision is himself a tender 48 years old. Before Knill-Jones tells us the history of his company and how at the young age of 25 he came to own it, he hands Louis McNair a box of gears. McNair is only 23 and looks it. Knill-Jones casually gives a short explanation of the work that needs to be done: Bevel this, ream that, make this pin, and other instructions that mean little to this layman. Although McNair is young, he hails from New Zealand, a country well known for its history of producing fine engineers and with it a spirit of mend and repair. Anyone who has seen the film The World’s Fastest Indian will already know this. By the time McNair was 21 he’d already built a microlight aircraft and restored a sports racing car that’s powered by a two-stroke Evinrude outboard motor.

Charles Knill-Jones was drawing bicycles and cars as soon as he could hold a pencil. “My mum said that I drove out of her womb,” he says. An alarming image, but petrol and engineering are clearly in the genes. “My grandfather was friends with Malcolm Campbell and although my dad ran the family printing company he owned a 12/50 Alvis.”

More importantly, Knill-Jones Senior was fully supportive of his son’s karting hobby. “He let me race karts from the age of 8,” explains Knill-Jones, “racing against guys like David Couthard. When I was 13 Dad asked me if I wanted to do a proper season of karting, funded as well as we could have afforded. I thought about it but instead I chose to go to boarding school so that I could be with my friends who were going.” Motor racing’s loss was academia’s gain as post school Knill-Jones studied material science and technology at Brunel University in Uxbridge, West London.

“I chose this course because I thought it would be the best way into Formula 1. It was a fascinating course and during it a team of us won the Ford Prize for technical innovation. We were among the first people to do 3D printing using engineering ceramics. We sold a patent to NASA for it. It was an interesting time but it made me realize that it was as near to theoretical work as I wanted to get. I also realized that Formula 1 would be very restricted. I wanted to be involved in a more hands-on world.”

That goal was achieved when Charles answered an advertisement in Autosport magazine for a young engineer to join Nick Mason’s Ten Tenths establishment to look after the Pink Floyd drummer’s comprehensive car collection.

“I started with Nick in 1996,” says Knill-Jones, “and within six months was sent to Tula Engineering in Cirencester to rebuild a Bugatti Type 35 that was being made for Nick’s wife Annette to race.”

Tula Engineering was founded by a chap called Richard I’Anson and one of his friends in 1969 to supply the burgeoning kit car industry with parts and services. Fate decreed, however, that the company would become one of the go-to specialists for Bugatti enthusiasts. “In 1998 Richard wanted to retire and asked me if I would take over running Tula,” says Knill-Jones. “Trouble was I really liked working at Ten Tenths. It was Nick Mason who came up with the solution: He suggested that I run the company out of the Ten Tenths premises and worked on Bugattis alongside Nick’s cars. It turned out to be the perfect plan. One of the greatest pleasures was taking Nick’s cars to various events around the U.K. and in Europe and the amazing characters that I met in historic racing. The sort of people that I would never have come across in F1.”

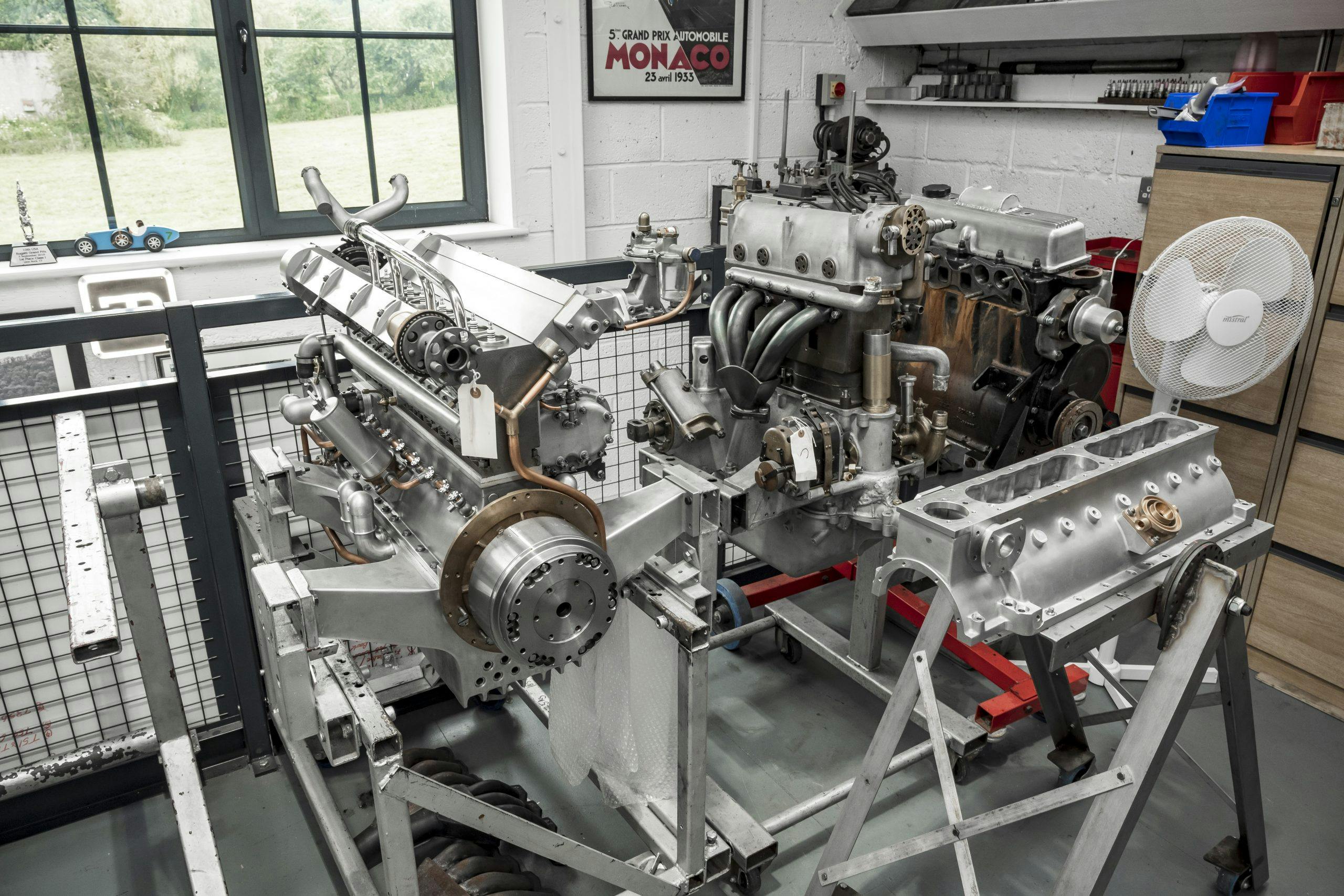

When you consider the hours involved in restoring the various different types of Bugatti, and Tula’s reputation, it should come as little surprise the company has about two years’ of work stretching out ahead of it. It handles minor jobs, ongoing care, motor sports preparation and complete, ground-up restorations, and as well as the U.K., clients come from France, Germany, and America.

To restore a Grand Prix Bugatti is, says Knill-Jones, around 2000 hours of work. A Type 59 takes that up to around 3000 hours—roughly the same as a touring type model—while a “Pebble Beach standard restoration can involve as much as 4000 hours of toiling.

“We like nothing more than getting our teeth into a full restoration,” he reports, “as the connection between and the car becomes so much deeper.”

Charles Knill-Jones made the move to this new premises in Northleach in 2019, taking on a building that used to be a sawmill. The attention to detail in converting it into a workshop—the high security doors themselves are a work of art in wood and galvanized metal—reflect the level of craftsmanship that you’ll find behind them.

The Bugatti Diatto Avio 8C is a thing of majestic beauty that, as well as being a formidable machine in itself, has a fascinating history. “Bugatti developed the engine for Italian engineering company Diatto who on September 23, 1916, sent Ettore Bugatti a telegram announcing that the engine had successfully run non-stop on a dynamometer for 50 hours and by the end was producing 210 horsepower. This engine is widely regarded as the basis for the Bugatti Royale’s eight-cylinder engine.”

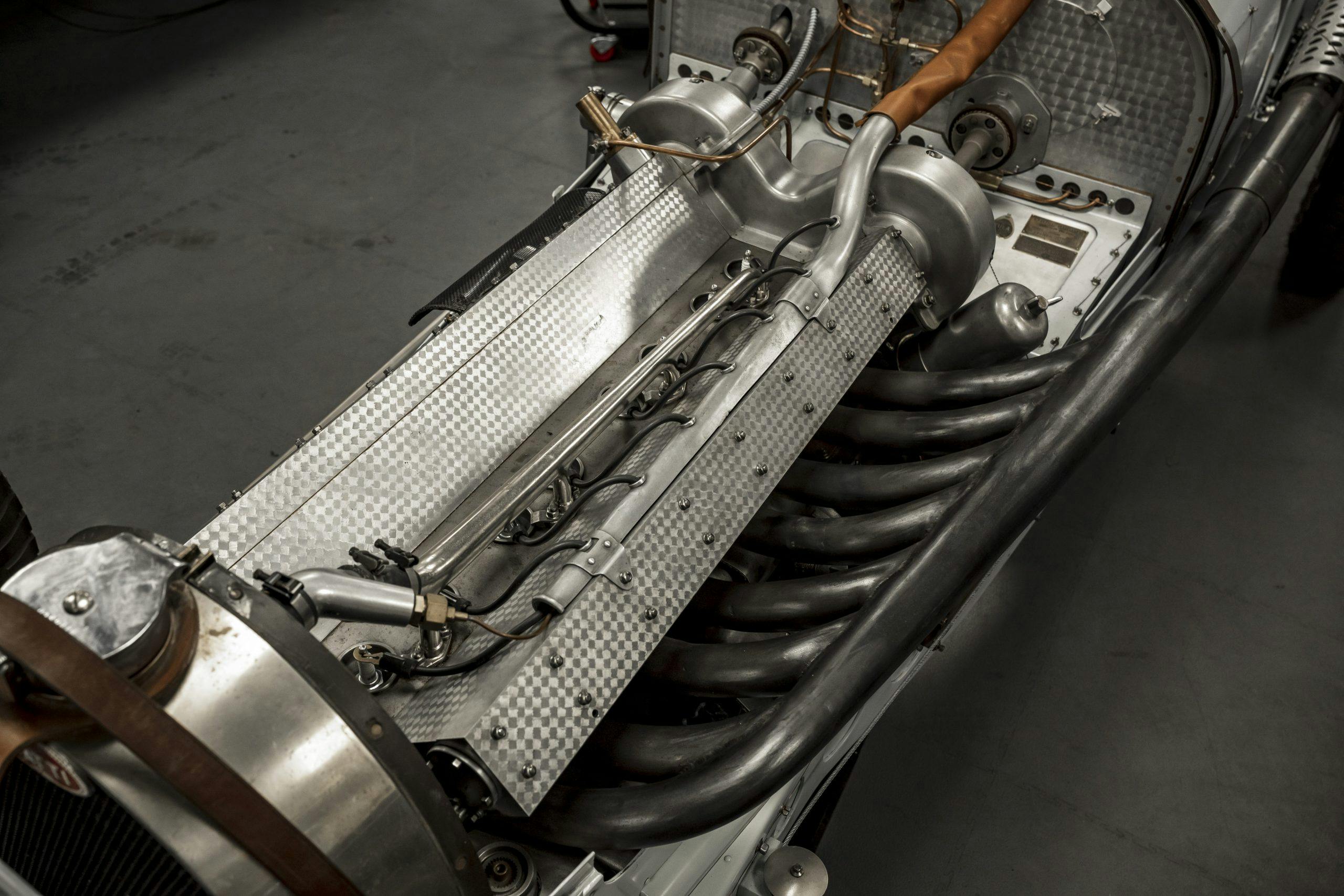

Found in a museum in Turin decades ago, the Bugatti-designed Diatto Avio 8C passed through several hands before the current owner commissioned Tula to bring it to life a century after its birth. It is a wondrous machine but for sheer beauty you cannot beat the Bugatti Type 59 that sits in the workshop a few paces from the Diatto. “This car is actually a replica that was built years ago by Tula,” points out Charles, “the Type 59 and the Brescias are without question my favorite Bugattis. The Brescia was a really amazing machine and was the forefather of the performance sports car. I used to have one but sold it to buy a house!”

You need an expert on hand to fully appreciate the details and the engineering highlights on the Type 59. To not have a guide as knowledgeable as Knill-Jones to explain them would be like visiting the Valley of the Kings without a guide. He’s busy building a Bugatti engine upstairs but the man for the job should really be Michael Whiting. Whiting has been at Tula for 50 years, almost from the beginning. He retires in September and with him will go an immense amount of knowledge and experience. It was he who built the Type 59 that we’re looking at.

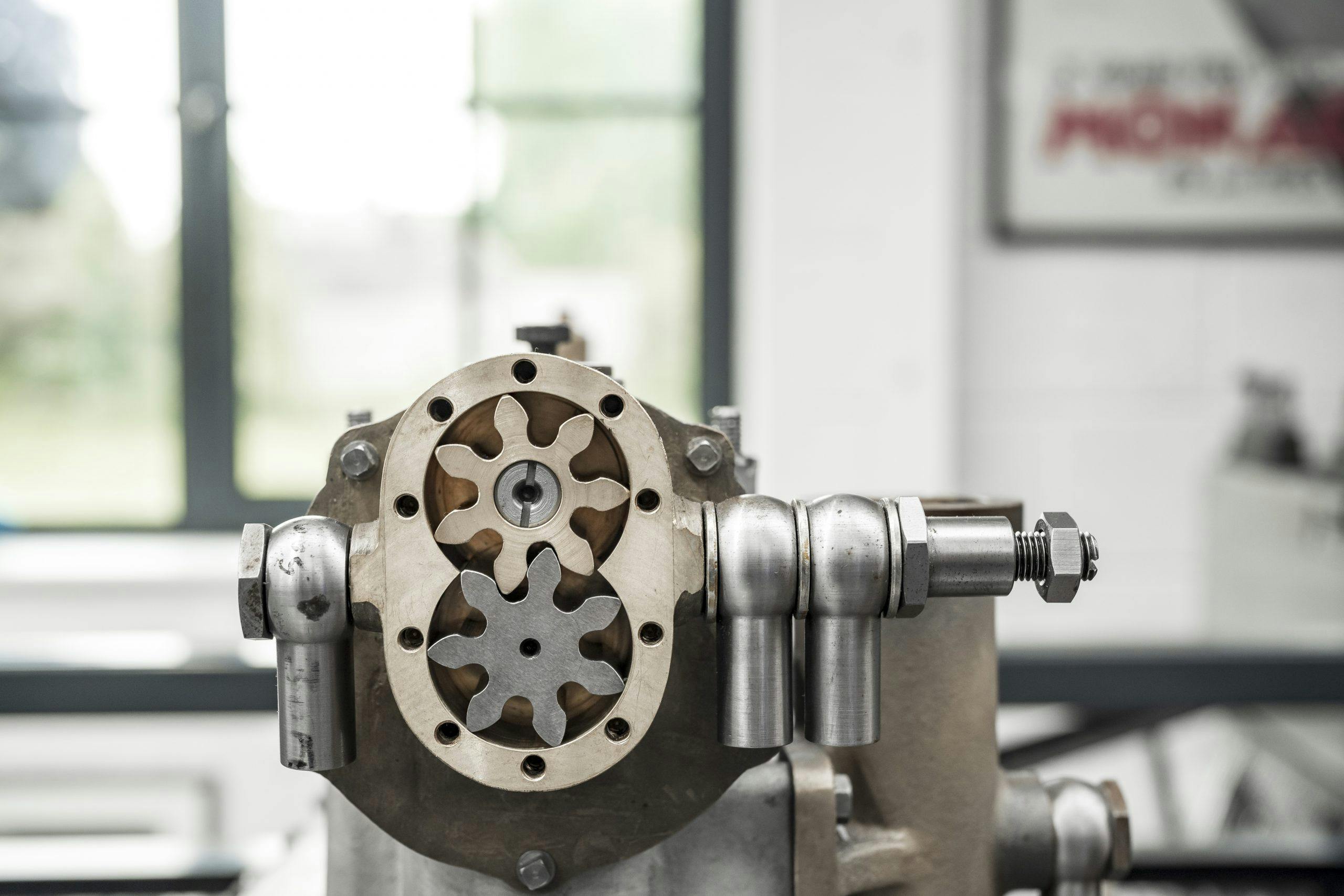

The Type 59 is the most gorgeous thing. Even if prewar racing cars are not your bag, anyone who has a passion for mechanical things cannot fail to fall in love with this machine. Not only is it a stunning looking machine, the detailing is incredible—from the hand-scraped hatched pattern on the cambox (it takes two weeks work to do that, explains Charles) to the gear-driven carburetor linkage. “Isn’t it wonderful?” asks Knill-Jones. “And look at the brake adjusting mechanism. Not only do the intricate chains and gears allow for brake wear front to rear, but also side to side. The attention to detail is simply stunning.”

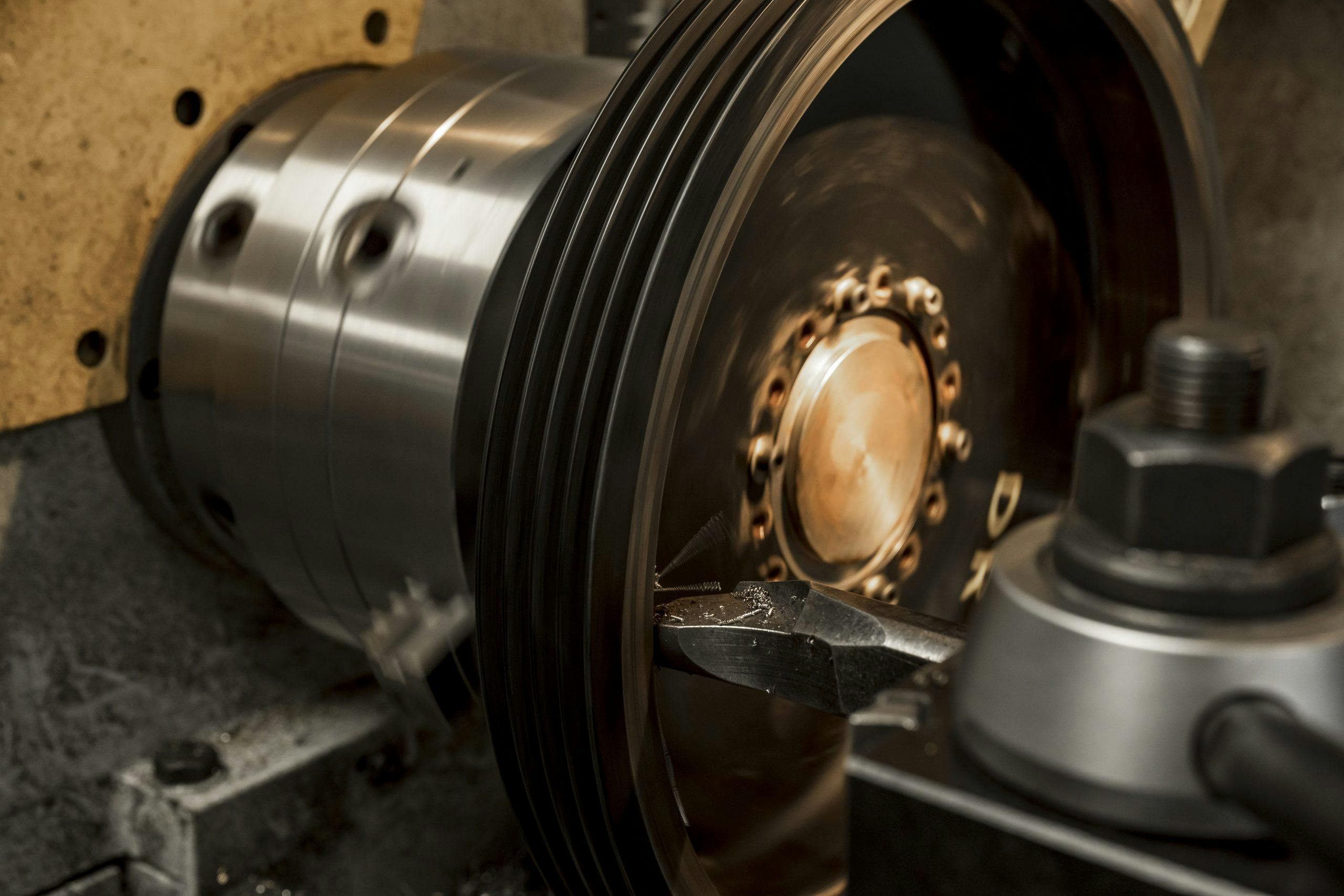

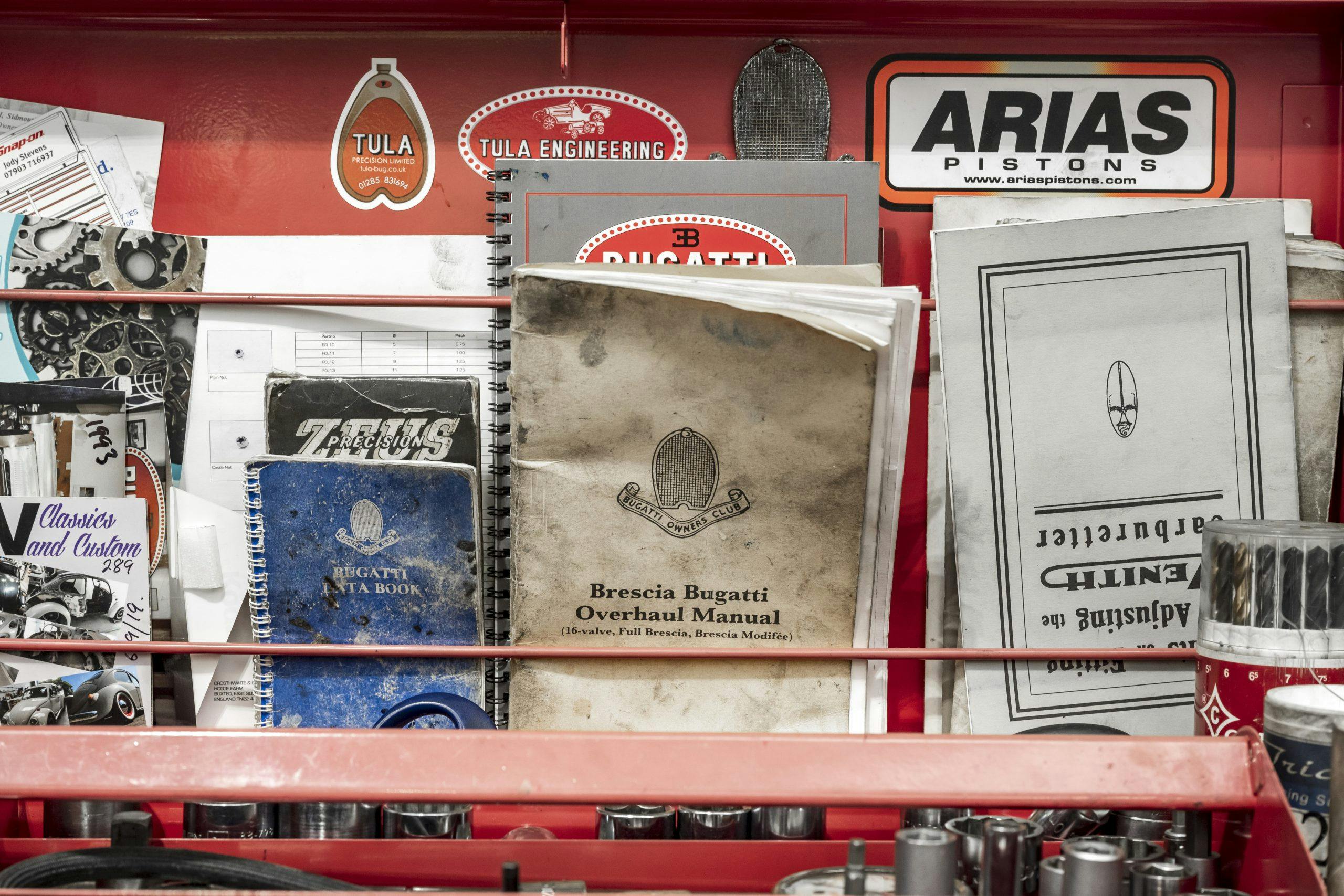

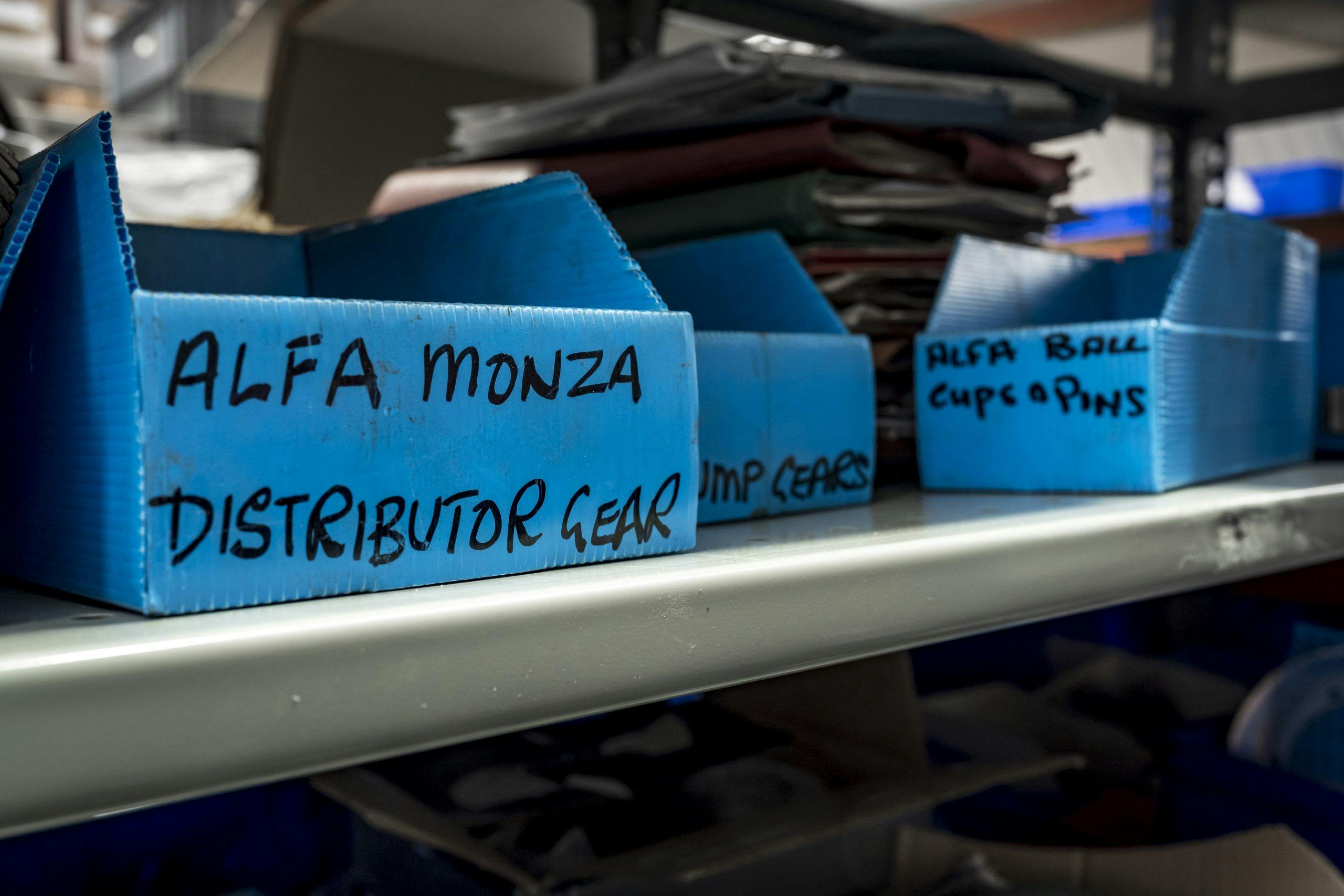

You’ll remember from all our visits to specialists that a crucial part of their businesses is collecting and preserving archive material. Not just important for the company itself, but for the future of that particular marque or detail. It is the same at Tula Precision. Filing cabinets contain priceless drawings of parts; shelves contain patterns from which extinct components can be remade.

But it’s the people at Tula Precision who, along with a handful of other specialists around the world, will ensure that Bugatti enthusiasts present and in the future have the technical (and moral) support that their incredible machines deserve. It’s a small team at Tula but each fulfills a crucial role. Trisha Davis is the parts controller and in a previous life ran the Bugatti Owners’ Club parts department. Her knowledge is invaluable. Ray Nash has been manning the lathes and milling machines at Tula since the 1980s. Louis McNair we’ve already met, but with him in the workshop is another youngster called Callum Frost. Frost came from Crosthwaite & Gardiner. Another of our past subjects.

Staff will come and go—that is life—but there’s no doubt that the beauty and stunning technical detail of Bugattis will entrance new generations of engineers and craftsmen. Youngsters who would perhaps rather set up the supercharger and carburetors on a Bugatti Type 59 than develop the software for the infotainment system on an electric Bentley. One thing’s for sure, Charles Knill-Jones will never be far from his tool chest and his beloved Bugattis.