Die-cast racing in 1/64 scale is a plastic, fantastic thrill

Perhaps you did not hear about the “incident” at a very small California track. Of course, that might be because the track is so small it cannot be found on any map. A racer named Bobby Johnson, barreling down a short mountain course in a Lancia 037 Group B rally car, came out of a curve too hot and wide and clipped a trackside photographer on the straight, sending him flying 80 feet down the mountain side.

The hapless shutterbug landed flat on his back in a paddock area, where a few heartless spectators aimed their phones to capture the man’s pain on video. The two caffeinated race announcers, who prior to the run had voiced safety concerns about “Group B action,” simply made jokes. Paramedics removed the incapacitated photographer, and racing resumed.

Johnson was not penalized for the hit, but his 18.568-second time down the half-mile course was more than three seconds behind winner Marcus Firegone in a Subaru WRX STI, knocking him out of the competition. But get this; the photographer, as it turns out, survived the drop.

Chalk it up to his one-and-a-quarter inch tall plastic body and the actual fall being just 16 inches.

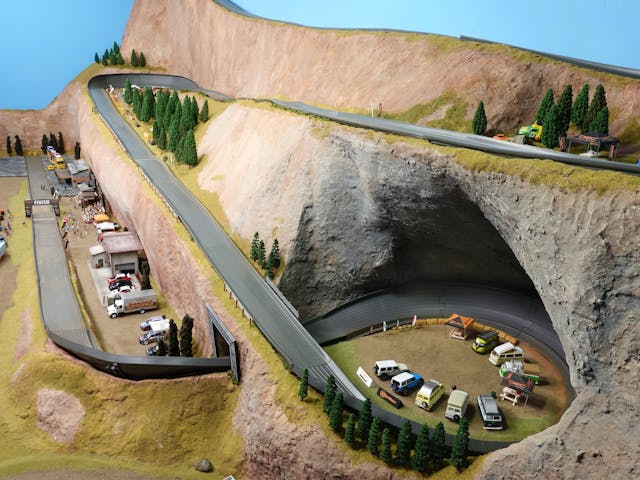

Welcome to the miniature yet hugely fun and unpredictable world of the Diecast Rally Car Championship. Created by Adriel Johnson, the DRC is one of several 1/64-scale gravity race series he runs on two highly detailed tracks that he built in his one-car garage. He produces broadcast-grade videos for his YouTube channel, called 3Dbotmaker.

The videos are jam-packed with thrilling racing action, including passing, bumping, drifting and crashing, with all the sounds that go with it. Johnson’s attention to detail and production values bring the tiny cars to life in a way that suggests a television racing channel. If the Pikes Peak International Hill Climb, a.k.a. “Race to the Clouds” that takes place in late June is the ultimate competitive uphill race, then Johnson’s garage might be home to the ultimate small-scale downhill races.

Johnson’s 3Dbotmaker racing, which started about four years ago, uses mostly Hot Wheels and Matchbox models, with some cars coming from the Tomica and Majorette lines. With 360+ videos posted so far, 530,000+ subscribers and 86 million views, Johnson’s tiny racing world has become a growing entertainment business, with Ridge Wallet as a sponsor and YouTube ad revenue coming in.

It all started pretty much by accident.

The plastic path to motorsports stardom

Following his son’s birth seven years ago, Johnson left his full-time job to become self-employed and work from home. When becoming an eBay reseller didn’t pan out, he bought a 3D printer to make accessories for the Hot Wheels track setups his son enjoyed and also began selling them online under the name 3Dbotmaker. He posted videos on YouTube to promote his products, but, as often happens with sudden YouTube success, things took a turn.

“The videos became bigger than the 3D printing business,” Johnson tells Hagerty. “Last year, I dropped the products to focus on the videos.”

By then, the filmmaking had evolved to include full-blown productions with elaborately detailed tracks and dioramas, as seen on the best slot-car tracks. Some of Johnson’s details include branded paddock areas, grandstands with cheering fans, infield camping and even Porta-Potties.

Notably, 3Dbotmaker is a one-man operation, with suburban dad Johnson running the races and producing the videos using a series of GoPro cameras positioned around the tracks.

“GoPros keep everything in focus, so there’s no shallow depth of field,” Johnson explains. “Plus, they have a high frame rate, up to 240 frames per second. There’s lighting all around the tracks needed to shoot at those high rates.”

Johnson uses smaller point-and-shoot cameras for fill-in shots. Cameras with smaller sensors, he says, work better for miniatures than cameras with large frame sensors. He does all the editing and sound design himself and also calls the races, voicing both announcers heard in the videos, “3D Botmaker” and his sidekick, “2D.”

Johnson, who left a career in computer information systems, had no prior professional experience in broadcasting. Video, photography, and audio had been hobbies since high school. He is self-taught, with no formal training in any of those fields.

Real racing, not-quite real time

Johnson is a car enthusiast, though, and that comes through in his work. The races are not rehearsed; the results you see how they ran. Cars are released at the start line, and gravity takes over from there.

“Each race is one take. The race is the race,” Johnson says. If a car should spin out and continue running the course backward, even flipping over and sliding across the finish line on its roof, that’s how it goes.

It is only when watching the full playback that Johnson creates the announcer audio. There are no scripts, just his on-the-fly commentary based what he sees in the video.

“I can’t see the whole race as it is happening, because I monitor the finish-line cameras to see who won and tabulate points that advance cars to the next round,” he explains. Only when viewing the playback does Johnson learn if a car passed another or crashed on the way down the track, for example.

“The fun thing for me is it’s gravity based, with random results,” he says.

The GoPros aren’t the only reason that 3Dbotmaker racing videos looks so oddly realistic. Johnson also slows the video to half-speed to compensate for the high car speed.

“The actual speed is too fast to watch,” he says. “I also programmed the race timer to double the race times to match the video speed.”

Here’s what that means: In 1/64 scale, Johnson’s 48-foot Race Mountain track works out to a bit over half-mile. A 17-second indicated time means an actual 8.5-second run down the track. With that time, the car’s speed would scale to about 250 mph. What you see in the half-speed video are cars maxing at about 125 mph (at scale).

From race to finished production, it takes Johnson about two days to produce a video. Filming and editing take up the first day, and the second day is spent adding the sound effects, voiceover and music. Johnson takes advantage of the spontaneity of the racing, for example running instant replays on passing maneuvers, which, of course, occur purely by chance. For the Lancia 037 incident, Johnson inserted an instant replay of the hit and, post-race, produced close-up shots of the aftermath.

Full calendar of events

In addition to the DRC series, Johnson conducts the Tournament Series and King of the Mountain (KotM) modified car series. He has also run special single-marque tournaments. A Ferrari Tournament run in early 2020 has earned more than a million views, while the Lamborghini Tournament from last spring has nearly a quarter-million views.

The DRC and Tournament races both use Johnson’s own cars, with many of the racer names submitted by viewers. The KotM, however, runs with modified cars sent in by viewers. Running contrary to Colin Chapman’s renowned “add lightness, then simplify” philosophy, these racers add heaviness to maximize gravity’s effect. Finding the optimal weight is the key, as the heaviest car does not always win.

Johnson points out that a standard current Hot Wheels car has a metal body on a plastic base and weighs about 30 grams, or a little over an ounce, The all-metal Hot Wheels Premium cars weigh about 45-50 grams. Because the rubber tires on those cars are not suitable for racing, Johnson swaps them out for the standard models’ plastic wheels.

Adopting a practice by Team Penske and Mark Donohue for the race team’s conquering Trans-Am Camaros in the late 1960s, KotM racers add weight at specific parts of their cars to optimize balance.

“The people who know what they’re doing will smooth out wheels, polish axles, add weight and add graphite to the wheels,” says Johnson. “It’s kind of like Pinewood Derby racing,” he adds, citing the famous Boy Scouts of America gravity racers.

The KotM series started without rules, but Johnson had to change course when a competitor sent in a car weighing a track-bending 220 grams (half a pound). The current rules call for a 65g minimum and 120g maximum. He said that one racer pours molten lead into the top of the bodies of his cars.

“It’s a bit toxic,” he says half-jokingly. “But these guys are serious.” His rules now forbid exposed lead and sharp edges on the cars’ exteriors.

As in real racing, the cars get nicked up, so don’t look for a vintage series using classic Hot Wheels models. (Might we suggest a “barn finds” series with old Hot Wheels cars that have already had the paint played off of them?)

Not your father’s toy track

Johnson has used four track configurations since starting. His current two include Race Mountain, which is used for KotM and stock car racing, and the Rally track, which has jumps for cars to get air.

For the track surfaces, Johnson has used products originally designed for motorized miniature cars. Hot Wheels Sizzlers Fat Track from the 1970s proved too wide, so he currently uses track from Crash Racers by Far Out Toys. It’s the same size as the older Hot Wheel X-V track, about two car lengths wide, he explains.

“The narrower track is better for keeping cars from spinning out and running down backwards,” he says, adding that it does not completely prevent such mishaps.

Future expansion

Johnson has an expanding vision for his creative scale-model race series. He wants to find a space that can accommodate five or six tracks and then increase video production. Right now, there is a possibility of sponsorship from a tire company, he tells Hagerty, plus an upcoming partnership with Japanese Nostalgic Car.

3Dbotmaker racing may have originated in a three-year-old’s Hot Wheels play sessions, but Johnson says his two children are these days more interested in dinosaurs, sharks and video games.

For those who still remember how playing with Hot Wheels track sets as kids sparked a love of cars, however, Johnson’s compelling videos fulfill a fantasy of miniature racing beyond the orange plastic road.

Been watching the DRL for a few years and really enjoy it! Adriel is great at what he does. I always thought that ‘2D’ was a friend of his, not him doing another voice!

“Race in Peace, McClyde” (If you know, you know)

Shake and Bake! Shake and Baaake!!!