Hard charging in Bentley’s $2M Blower continuation car

Imagine the meeting at Bentley when the question arose of how to teach a select group of automotive journalists to drive the prototype £1.5M ($2.08M) Blower continuation car. “Why not put them in the £25M original?” someone must have suggested. And apparently no one disagreed.

So I am at Millbrook Proving Ground, a vehicle development facility south of Bedford, U.K., about to be taught how to deal with a central accelerator pedal and “crash” gearbox in one of just four of the supercharged 4½-liter Team Cars built by Sir Henry “Tim” Birkin in 1928 and ’29. Only when this is mastered will we be allowed to try Car Zero of the new Continuation Series. Interesting.

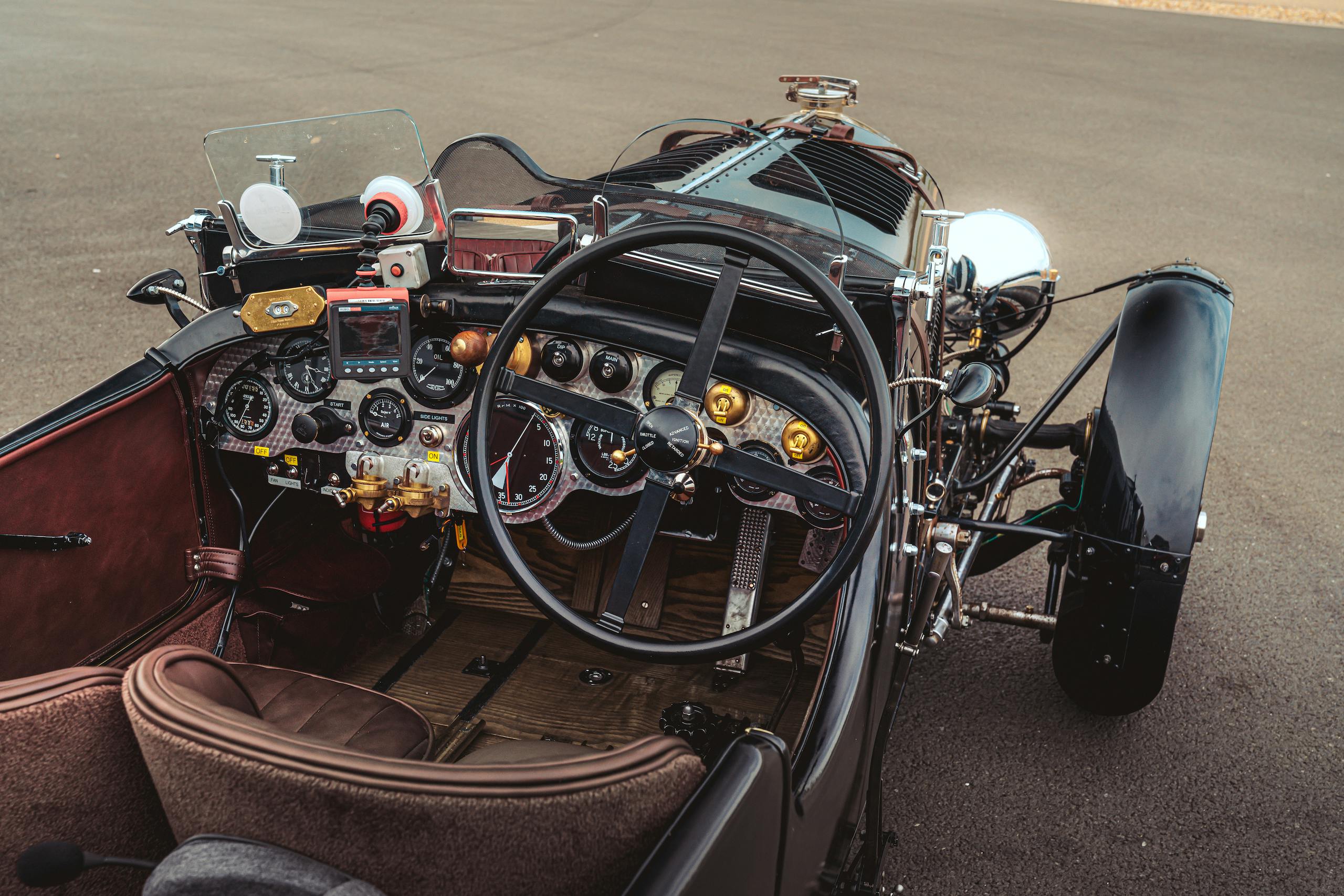

There’s a logic though, because the notorious Bentley gearbox gets easier to manage with age, and Car Zero—the development car that acts as the prototype for this high-profile rebirth of one of Bentley’s most significant cars—has covered just 1500 miles of its 5000-mile test program. Indeed, it’s still kitted out with instrumentation to monitor temperatures and pressures as it clocks up an average of 200 miles a day around Millbrook’s famous Alpine circuit and high-speed bowl. And of course by hopping from the 90-year-old original to the brand-new recreation, we’ll be able to compare the two cars directly.

Let’s rewind first, though, initially all the way back to the 1920s, when Bentley was riding high building upmarket sports cars and winning Le Mans. Though W.O. Bentley was at the helm, the company was reliant on the custom and backing of its most prolific racers, collectively known as The Bentley Boys. They included gentleman racer Sir Tim Birkin, who was sure that the way for further racing success was not through W.O.’s plans for larger, heavier engines but by supercharging the existing 4½-liter four-cylinder model.

W.O. was not convinced but Birkin forged ahead, persuading Bentley chairman Woolf Barnato to agree to the production of 55 cars—including five allocated for competition—to meet the homologation requirements of the day. With financial backing from wealthy heiress Dorothy Paget, Birkin built four race cars in his own workshop; the second of these four “Team Cars” is the one here, known as No. 2 or UU 5872, owned by Bentley Motors since 2000.

Bentley has used Team Car No. 2 for years for shows, displays, and even rallies, and it was beginning to look and feel rather tired. Sympathetic restoration was required. Meantime, the continuation car trend was hotting up, with commercially successful offerings from Jaguar and Aston Martin in particular. Why not take the opportunity to digitally scan every part of No. 2 in order to produce copies, to be built by Bentley’s newly-revived bespoke Mulliner division with help from vintage Bentley specialists, William Medcalf, Graham Moss, and Neil Davies Racing.

The project started in earnest in early 2020 only to be delayed, of course, by the pandemic. As with all these high-profile manufacturer-led continuation programs, Bentley has completed a “Car Zero” prototype ahead of the customer cars, and it’s that car that I’m about to drive.

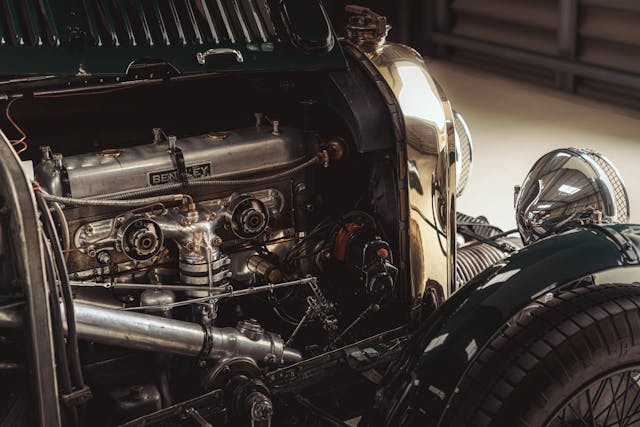

So what’s the big deal about driving these vintage Bentleys? On the face of it they seem conventional: a four-cylinder, 16-valve engine producing 240 hp at 4200 rpm, driving a live rear axle via a four-speed gearbox, all sat in a hefty ladder chassis.

Where difficulties come is in the details. Of the three pedals, the accelerator is in the middle, the clutch to the left, the brake much higher, on the right. The handbrake is on the exterior of the car. The four-speed gearbox doesn’t have synchromesh and the gear lever is on the floor, almost under the driver’s right thigh. The steering is famously heavy at low speeds (and most other speeds). There’s a lever on the steering wheel to advance and retard the ignition: more advance is needed the faster the car is traveling.

None of this is a problem once you’re used to it, but it takes some acclimatization. After a few minute’s instruction, it’s my turn in the original—£25M, remember—Team Car. Twin ignition magnetos on, fuel pump on, check (again) it’s in neutral, press the starter button and the engine roars instantly into life. Clutch right the way down, gear lever pushed firmly forwards, up with the clutch and a touch of accelerator and the Bentley eases smoothly forward.

As speed builds, it’s time for the first test of skill. Off the accelerator, clutch right down as I pull the lever into neutral, right up with the clutch and then straight back down again as I pull the lever backwards into second. It snicks straight in. Wow.

The great torque of the engine is propelling this 1500-kg (3300-pound) beast forward at surprising speed, so it’s time to try third gear. Again, clutch down and lever forward into neutral, clutch up and then quickly back down again at the same time that the gear lever is pushed across and forwards. Straight in again! If there had been an audience, I swear I’d have given a victory wave. Pride before the fall, and all that …

Because now I have to try shifting back down into second. Same process but this time the accelerator needs a blip while the clutch is up and the lever in neutral. If the revs are matched, then it should slot neatly into second once the clutch is back down to the floor. It doesn’t. There’s a crunching of teeth and I let the car coast as we arrive at a banked corner, desperately reminding myself to move my foot to the right, not the left, to press the brake pedal. The huge drum brakes slow us down surprisingly well, and I’m left trying another throttle blip to match the engine revs to the gearbox speed.

Nope, that didn’t work. Seems you don’t “blip” a heavy Bentley accelerator, you shove it. But my brain is overloaded, and I’m now trying to raise the revs while the clutch is down, all the while still coasting in neutral. The advice is to just come to a halt and start again, but one last attempt and we’re in second and accelerating back down the straight.

I find I’m weirdly rattled by my failure. I’ve driven pre-war cars before, including early 1900s Veterans on the London to Brighton Run, but over the next few minutes I fall apart, perspiring in my crash helmet and face mask. I try third. I fail. I try second but my feet aren’t doing what my brain knows they should be doing. I realize I’ve knocked the little reverse gear gate protection out of place, which partly explains the difficulty changing into third, but I continue to struggle.

Finally I get it right, but now I’m putting off the gear changes, holding back on sampling the impressive acceleration of the Bentley. The steering wheel jiggles around in my hands, the exhaust bellows, but I know we could be traveling faster. One last turn into the holding area, and even then I don’t wrench on the steering wheel with enough vigor. so the car only just makes the turn. My mouth is dry and I’m truly annoyed with myself.

There’s no let-up, because it’s out of the Team Car and straight into Car Zero. Magnetos and fuel pump on, a press of the starter button and it’s alive as quickly as the Team Car. The clutch is lighter, the accelerator a little heavier, but it’s otherwise exactly the same setup, except that the gearbox is brand-new and apparently more difficult to master.

Just those few minutes of getting out of one car and into the other has given my brain time to reset. As I found right at the start, if I just do what I know I need to do, almost without thinking, then the gears slot in reasonably sweetly. First to second needs a slight pause, second to third needs as fast a change as is possible while double-declutching, and third to fourth is somewhere in between. Of course I mess up occasionally—everyone does—but this time it’s less traumatic.

Now I can really experience the torque of the engine—an engine that was first brought to life on a test bench that was once used for Spitfire airplane engines. It’s a little smoother than the Team Car’s and it’s even happier to pull from low revs. It doesn’t splutter or hesitate, it just seems to broaden its metaphoric shoulders, deepen its voice and propel the car forward more quickly than a 92-year-old car has any right to do. This car is fast. The exhaust and the wind buffeting means I don’t consciously hear the whine of the supercharger but it’s clearly doing its job, providing the same amount of boost as the Team Car’s blower.

But the brakes … Car Zero’s brake shoes are still bedding in, so even the hardest shove isn’t slowing the car as steadfastly as expected. Pulling on the external handbrake helps but really it’s just one of those things to work around, rather like the steering, which gets lighter as speed increases but is always going to be heavy to the point that it’s often the limiting factor in ability (or confidence) to take a tight corner.

Those Bentley Boys must have been made of much stronger stuff to race these cars; though even now, Vintage Bentleys are raced and rallied at remarkable speeds, and their legendary strength and durability means they’re a popular choice for the 8700-mile Peking to Paris Motor Challenge rally, for example.

And that’s where these Continuation cars come in. Just 12 will be built, one for every race that the original Team Cars competed in, and all sold quickly—none of the 12 is even fully built yet. Some are going to Bentley collectors, some are going to customers who’ve never previously owned a truly vintage car, some will be raced and some will be rallied. It’s thought that at least one will be used in place of the owner’s original car to help preserve its precious history.

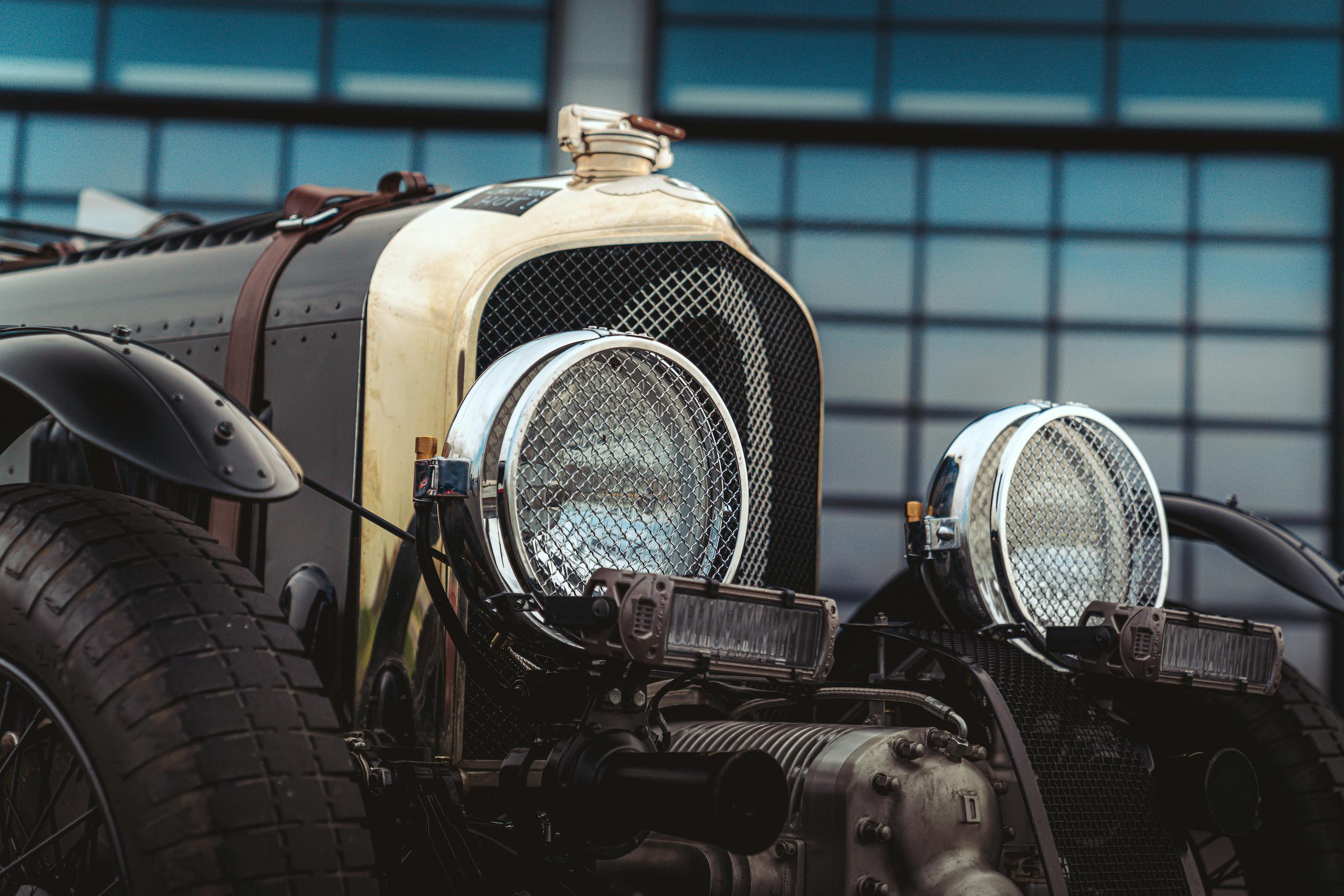

I don’t think they’ll be disappointed. Because this isn’t a rough replica or pastiche of the original, it is as close to the real thing as possible. The original chassis were made by a Glasgow shipbuilding company; the Continuation chassis are formed and hot-riveted to the same methods by a company that specializes in making boilers for steam trains and traction engines. The originals used components cast in Electron, a magnesium-based alloy, so that’s what the Continuation cars’ components are created in.

The body is created from ash wood, just like the original, covered in genuine Rexine cloth only made available again in the last decade thanks to Bentley specialists RC Moss. Customers have a choice of five authentic period Bentley colors, including the dark British Racing Green that No. 2 has been painted in at least since the 1960s and the Parsons Napier Green that it’s thought to have been previously painted in. Likewise the upholstery, recreated by Bridge of Weir in a choice of authentic colors. Apparently Oxblood is the popular choice so far.

In all, Bentley says 1846 individual parts were designed and crafted, though it turns out that more than 200 of those “individual parts” are actually assemblies, including the engine, which has been recreated in conjunction with specialists NDR. The total parts count is in the thousands.

Direct from Bentley these Blower Continuations aren’t allowed to be used on public roads, but it’s no secret that once in their home territories owners will generally be able to have them made road-legal. It’s pleasing to confirm that they’ll get the authentic Blower Bentley experience, just as the Bentley Boys would have more than 90 years ago.

Via Hagerty UK