Daredevil Debbie: America’s motorcycle jump queen who took on Knievel and won

“I can spit further than she can jump.” That was Evel Knievel’s answer to Debbie Lawler, who on February 3, 1974, launched her Suzuki TM250 motorcycle over 16 Chevy pickups parked mirror to mirror on the floor of the Houston Astrodome. Up until this jump, every distance record earned by the daredevil from Oregon came with an asterisk and some footnote about her gender. This feat was different—Lawler’s 101-foot leap was farther than any other rider had soared indoors, Knievel included.

Editor’s note: This article originally appeared in the March/April 2021 issue of Hagerty Drivers Club magazine, alongside our cover story showcasing Evel Knievel’s stranglehold on Seventies pop culture. Read all about Evel’s empire here.

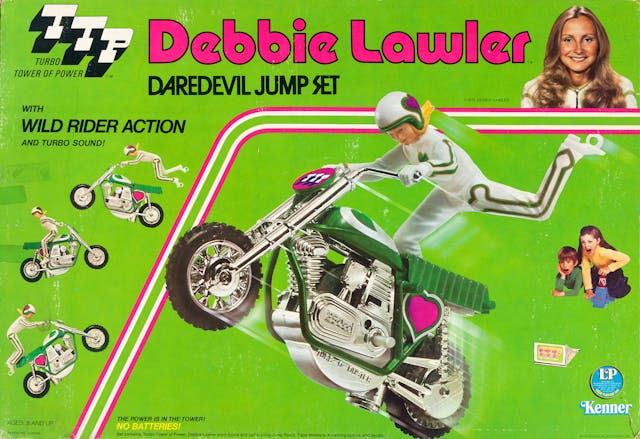

Didn’t matter if Knievel was a fan, the rest of the world was smitten with the rider in pink and powder-blue leathers. In the wake of her record jump, Lawler made appearances on television and in magazines. At 21, she became the first female athlete to have her own action figure, a riff by Kenner on Evel’s 1973 action figure, called the Debbie Lawler Daredevil Jump Set.

Despite her youth, Lawler had already been riding for over a decade, ever since her father gave her a motorcycle for her 10th birthday. Debbie and her two sisters tore up Grants Pass, Oregon, and the Pacific coast. “Motorcross, flat track, hill climb—we did anything on a bike,” says Lawler. “And my dad, who was an ex-Navy frogman, was always fighting for me and my sisters to race against the men.” Eventually she was recruited by a motorcycle stunt troop where she learned to fling her bike over long distances. Says Lawler: “Jumping through the air on a motorcycle gives you the most incredible feeling. It’s euphoric.”

Known as “the Flying Angel,” Lawler was a graceful stunt jumper and a better technical rider than Knievel, often launching in a perfect arc and arriving squarely on the painted pink heart that decorated her landing ramp. Sure, Lawler was a lighter package than Knievel on his hog, but her airborne accuracy and grace were largely a product of time invested in practice. “I know Evel says he didn’t practice. Well, I did,” says Lawler. “I practiced because I didn’t want to crash. He had so many crashes. If I crashed, I’d be toast.”

That day came on March 4, 1975, when Lawler was attempting a jump over 15 Datsuns at California’s Ontario Motor Speedway. As she launched, a fierce tail wind pushed her beyond the landing ramp. Calm and collected mid-crash, Lawler did what she always had been taught: put distance between her 100-pound body and her 220-pound bike. She rolled away from the bike. “But I went off the wrong side,” says Lawler. “I slammed into the cement retaining wall and broke my back.”

Debbie Lawler was just as tough as Knievel, and less than two weeks after the accident, she was a guest on The Mike Douglas Show, having flown to be on the Vegas set in Mario Andretti’s private jet so she could sit comfortably in her wheelchair. It was on Douglas’s show that Knievel surprised her as a guest. Apparently, he had since recanted, and he gifted the stunt rider a pink mink coat with “Happy Landings, Evel Knievel” sewn into the lining. “Evel Knievel was the king of motorcycle jumpers,” says Lawler. “I was the queen.”