Legends of Motorsport: Eliška Junková

Eliška Junek was known as the “Queen of the Steering Wheel,” so formidable were her racing skills. She competed successfully in the 1920s against the great drivers of the era, including Louis Chiron, René Dreyfus, Luigi Fagioli, and Tazio Nuvolari. Along with Hellé Nice, she was one of the only women racing in major events of the day and the first to win a Grand Prix event. After a racing accident took the life of her husband, however, she would never compete again. For a while, her star burned brightly, proving that women could compete successfully against men. She led the way for women drivers such as Janet Guthrie, Shirley Muldowney, and Danica Patrick.

She was born Alžběta (Elisabeth) Pospíšilová on November 16, 1900, in Olomouc, Moravia, in the Austro-Hungarian empire. The sixth of eight children, her childhood nickname was “Smíšek,” due to her ever-present smile. Following the end of World War I, her native Moravia became part of the new republic of Czechoslovakia. When she was 16, Elisabeth took a job at a bank, where she met a young banker by the name of Vincenc “Čeněk” Junek. He was six years older than she, and the two soon began a courtship. Elisabeth’s work with the bank took her first to Brno, then Prague, and then abroad to France and Gibraltar. She eventually returned to Paris to be reunited with Čeněk, who had become wealthy enough to indulge his automotive enthusiasm. Elisabeth remarked, “If he is going to be the love of my life, then I better learn to love these damned engines.”

However, Elisabeth soon fell under the spell of the sports cars of the period, especially Bugattis. The couple returned to Prague in 1922, where Elisabeth took secret driving lessons to earn her license. Meanwhile, Čeněk had started racing in earnest. He won the Zbraslav-Jíloviště hillclimb in 1922, the year they finally married. Upon her marriage to Čeněk, Elisabeth changed her first name to Eliška (Beth) and her surname to Junková, the feminine form of Junek in Czech.

In October 1922, the couple bought a Bugatti Type 29/30GP that had previously been raced in the French Grand Prix; the Type 29/30GP was the first Bugatti with a straight-eight engine. Initially she served as the riding mechanic to her husband, but a hand injury he had suffered during the war affected his ability to shift gears, so she had the chance to take the wheel in his place. Eliška’s first professional race was in 1923, with Čeněk at her side. The following year, she raced by herself and won her class at the Lochotín-Třemošná hillclimb. The victory made her a national celebrity overnight. She then placed first at Zbraslav-Jíloviště in 1925, after which the Juneks bought a second Bugatti to celebrate. (Eventually they would establish a close friendship with Ettore Bugatti.) By 1926, Eliška was confident enough to compete in races throughout Europe. She quickly gained fame across Europe and earned the nickname “Queen of the Steering Wheel.”

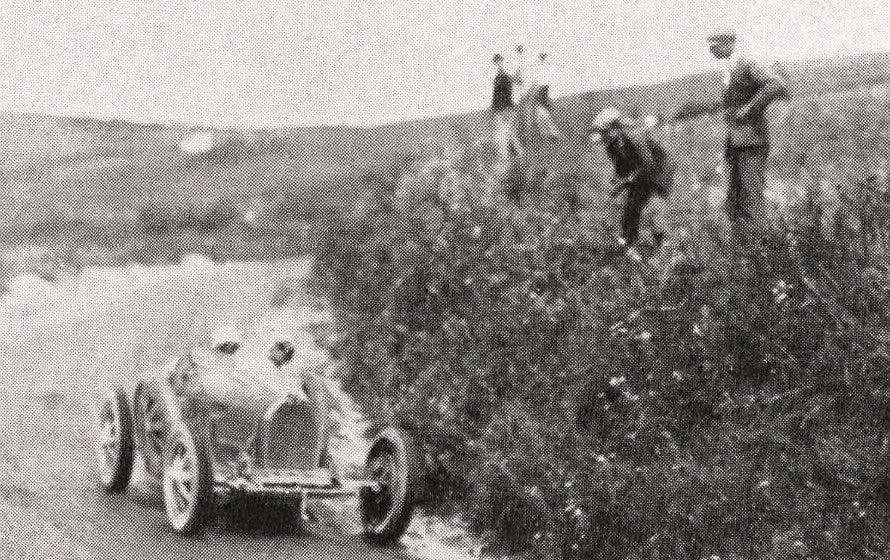

In 1926, she was the runner-up in the Klausen Pass hillclimb in Switzerland. She competed in the Targa Florio in Sicily for the first time in 1927, driving a 2.3-liter Bugatti Type 35B with Čeněk accompanying her as mechanic-passenger. The Targa Florio was a grueling eight-hour race that wound its way over mountain roads; stamina was as essential as speed due to the demands of the rough and often muddy course. That year, the race consisted of five laps of the 67-mile circuit for a total of 335 miles. With a strong start and at the end of the first lap, Eliška’s elapsed time of 1 hour, 27 minutes placed her fourth and just 10 seconds behind the works Bugatti of Emilio Materassi and ahead of the works Maserati and Peugeot. Unfortunately, her impressive run ended abruptly one-third of the way into the next lap when the steering gear broke, throwing Eliška and Čeněk off the road. Fortunately, neither was injured. This performance earned Eliška great respect from both her contemporary drivers and spectators alike. Shortly thereafter, she won the Brno-Soběšice hillclimb and then won the 2.0-liter sports-car class of the German Grand Prix at the new Nürburgring circuit.

Despite her diminutive stature, Eliška’s talent and technical driving expertise earned her great standing. She is often credited as being one of the first drivers to walk a course before an event, taking note of landmarks and determining the best line to take through corners. With her sights firmly fixed upon winning the 1928 Targa Florio, she purchased a new Bugatti Type 35B with a supercharged 2.3-liter inline-eight to stay competitive with the top male racers. Vincenzo Gargotta, one of the race’s press officers and a local resident, accompanied Eliška on reconnoitering the course. Periodically she would stop to put chalk marks on posts, walls, and trees along the route. The field was strong, with works entries from Alfa Romeo, Bugatti, and Maserati. On race day, the cars were flagged off at two-minute intervals, with Eliška starting well into the second half of the grid. The fastest driver on the first lap was Louis Chiron in his works Bugatti, followed by Giuseppe Campari in an Alfa Romeo, and then Chiron’s teammate, Albert Divo. Eliška was in a remarkable fourth place on elapsed time, barely 30 seconds behind Chiron, demonstrating her skill and the importance of her meticulous preparation.

On the second lap, Chiron pushed too hard and went off the track. Divo had pitted, which put Eliška (dubbed “Miss Bugatti” by the locals) in the overall lead, having passed many of the twenty cars that had started ahead of her. Divo, an experienced Grand Prix veteran, had started ahead of Eliška; following closely, she was ahead of him on elapsed time. After 4.5 hours, Campari pushed to take the lead by the end of the third lap. He built his lead, only to lose time with a tire puncture and drove the last six miles on the wheel rim. Heading into the final lap, Eliška was still in second and had closed to within a minute, with Divo ten seconds back. Campari crossed the line first, but since he had started 40 minutes ahead, the rest of the field had to finish to determine the actual winner. The first to appear was Caberto Conelli in his works Bugatti T37, finishing faster than Campari. Divo came through faster still and all were looking for Eliška to cross the finish line. It was not to be, as in the last half of the lap she had suffered a tire puncture, losing two critical minutes while her husband, serving as mechanic, changed the tire. The engine also overheated during the stop and they were hindered by the loss of water, so Eliška had to back off the throttle to nurse the car to the finish. She placed a commendable fifth out of only twelve finishers, almost nine minutes behind the winner, Divo, and beating top drivers such as Luigi Fagioli, René Dreyfus, Ernesto Maserati, and Tazio Nuvolari.

Eliška was back at the Nürburgring two months later, sharing the driving with her husband in the German Grand Prix (which was run as a sports-car race that year). On the fifth lap, having just changed places with her, Čeněk was rushing to make up lost time after a tire change. He went wide at the Breitscheid corner, hit a rock, and rolled the car. Although thrown free, Čeněk collapsed and died soon after from a head injury. Eliška was devastated and gave up racing as a result. She sold her vehicles and returned to her first passion, travel. Ettore Bugatti presented her with a new touring car for her trip to Sri Lanka (known as British Ceylon, in those days) and hired her to find new business opportunities in Asia.

Eventually Eliška found love again and married Czech writer Ladislav Khás shortly after World War II. From 1948 to 1964, however, the Communist authorities refused to allow her to venture abroad, disapproving of the high-flying, “bourgeois” lifestyle that she had lived. Like Hellé Nice, her great French counterpart, Eliška was largely forgotten by the racing world. In 1969 she attended the 40th anniversary of the Bugatti Owners Club in Great Britain. In 1973, she published her autobiography, Má Vzpomínka Je Bugatti (My Memory is Bugatti). She lived well into her nineties, long enough for the Iron Curtain to fall and for the Queen of the Steering Wheel to have her place in the annals of racing history recognized. (Bugatti even honored her with a special-edition Veyron in 2014.) In 1989, at the age of 89, she attended a Bugatti reunion in the United States as the guest of honor. It was a fitting final tribute to a woman who blazed a path for so many women to follow.