This motorized bicycle reveals the ingenuity of small-town America

Yawn, nod, or tweet; that’s all it takes to miss Galesburg, Kansas. According to 2019 census data, it held a population of 190 residents. In 1910, that number hovered around 183. This tiny Kansan town was the original home of Stanley W. Shaw and the Shaw Manufacturing Company, early purveyors of American gadgetry whose work became internationally recognized in-period and has proved collectible to this day.

According to southeastern Kansan lore, Stanley Shaw was a natural prodigy who got his start tinkering on the family farm. Born in 1881, he assembled his first bicycle at 8 years old. Two years later, his fascination for moving parts led him into the world of clock-making. At 14, Shaw built his very first steam engine, allegedly with two bike pumps and a well-pump cylinder. He kept pace with the world beyond Galesburg by altering his focus from steam to gasoline and in 1902 founded an early version of the Shaw Manufacturing Company, housed in a rented space inside the town’s old drug store. That’s when Shaw’s fortunes began to speed up—literally.

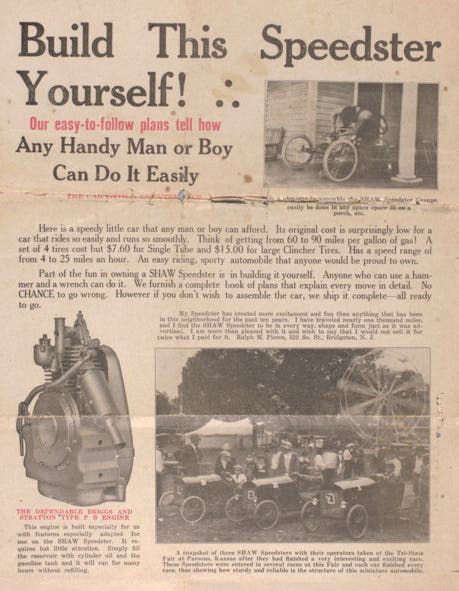

Imagine you’re walking the chalk-colored streets of Galesburg in 1903, unraveling an issue of The Kansas City Star, and a motorized bicycle hums by you at 35 mph, leaving a trail of pale dust. You guessed it—the rider, and builder, of the contraption would be Stanley Shaw. With this combustion-powered, two-wheeled machine, Shaw became known as the first motorized vehicle owner in the region.

Orders flooded in—13,000 total, at $53 a pop, for Shaw’s patented 2.5-hp, air-cooled engine. Shaw also sold a customized bike frame to fit the engine, should the customer want the complete package. Over the years, Shaw’s motor bicycles have become niche collectors’ items. In January of 2021, we found two examples either for sale or recently sold by two of the larger auction houses, Bonhams and Mecum. Shaw didn’t stop with bicycles, though. He quickly expanded his company and motorized all sorts of things, building air- and water-cooled engine variants for both land- and water-based applications as customers saw fit.

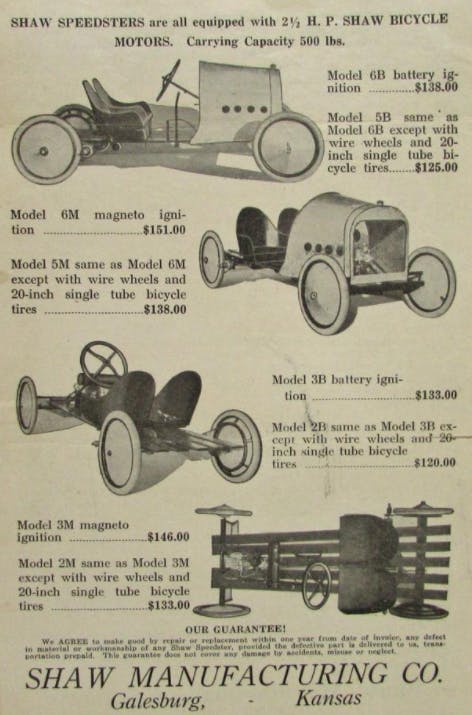

In 1908, Shaw Manufacturing introduced the Shawmobile, a 6-foot-long, roofless motor car powered by the company’s single-cylinder 2.5-liter engine. The automobile was capable of hitting 25 mph and achieving a comically high 90 mpg (not in a top-speed run, naturally). It sat two and cost only $150. (For context, Ford’s Model T debuted a year later carrying a price tag of $825. The Model T was much larger and far more refined than the Shawmobile, but, in an age in which most saw cars as a luxury, the Shawmobile got people on four wheels relatively inexpensively.) The Shawmobile would later get reworked as the Speedster.

A fascinating sign of the times—and of Shaw’s products in particular—is found in period advertising. Shaw Manufacturing placed fun at the forefront of its messaging, educating potential buyers and emphasizing the creative possibilities of its 2.5-hp motor. Clearly, Stanley Shaw hadn’t forgotten the mechanical enthusiasm of his younger years and sought to encourage it in others.

Shaw briefly invested further into the motorized bike realm by acquiring the Kokomo Motorcycle Company, in Kokomo, Indiana. That pursuit ran its course by 1920, however, and Shaw Manufacturing redirected its efforts into vehicles that would eventually prove its bread and butter: farm tractors, garden tractors, and other farming implements.

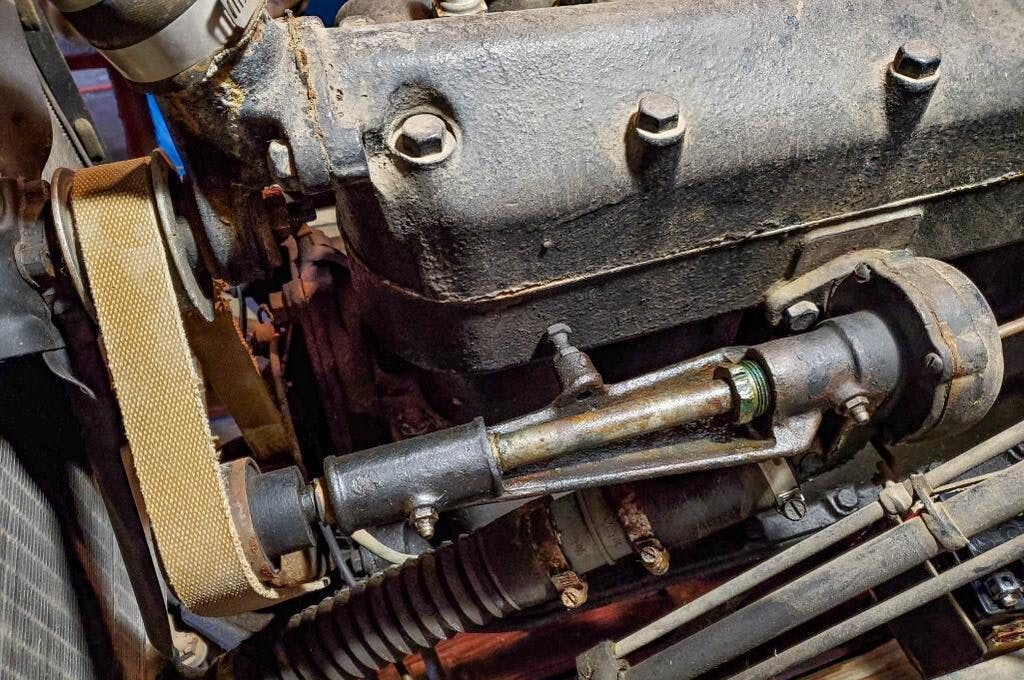

After World War I, production costs for large-scale automobile manufacturers were dropping steadily. Rather than dive into the cutthroat business of mass-producing passenger cars, Shaw focused on the less competitive, less risky agriculture sector. Shaw Manufacturing hit the ground running in the early ’20s only to lose some momentum as it churned through a few hard years of research and development. It’s during that period that Shaw Manufacturing created this rare 1924 Model T Ford Tractor conversion, now up for auction in Howard, Kansas, about an hour due west of Galesburg.

This particular tractor distinguishes itself as a demonstrator creation that was later sold off during the Great Depression. Rumor holds that this Shaw Model T Conversion was destined for scrap but survived thanks to a local farmer who fancied the old tractor and struck a deal with the yard.

Shaw’s car-to-tractor conversions are not common, chiefly because the company had a monumental breakthrough with its patented Du-All T-25 garden tractors in 1924. For the next four years, the popularity of the original Du-All spurred Shaw Manufacturing’s expansion into field offices in New York City, Chicago, and Columbus, Ohio. The Du-All was in such high demand that Shaw Manufacturing, who had outsourced the Du-All’s powerplant, simply couldn’t source engines fast enough; it was forced to call up Briggs & Stratton to supply more. Du-Alls even found their way into Europe—and for good reason. With high-arch, riding, and walking variations, the Du-All model range lived up to its name, earning a reputation as the “tractor of 100 uses.”

Prosperity brought opportunity, and Shaw had ample opportunities to leave Galesburg. However, he never relocated the business and chose to build a second factory in Galesburg instead. The thought of retirement didn’t come easily or often to Stanley Shaw, either; he remained at the helm of Shaw Manufacturing until he was 81. In 1962 he finally sold the business to Bush Hog of the Alamo Group. Shaw Manufacturing Company had employed over half of Galesburg during Shaw’s tenure. He was laid to rest in Galesburg at the fine age of 100.

If you find yourself passing through Galesburg, or a town like it, stop for a while. Look up from that tweet. Take a moment to appreciate the wide-spread contributions of small-town American inventors like Stanley W. Shaw.