From home garage to Pikes Peak, this Texas tuner is all about Evos

If you grew up playing Gran Turismo and other driving video games, pat yourself on the back; you are a big part of the reason that the Mitsubishi Lancer Evolution and Subaru WRX/STI made it to America. When gamers became licensed drivers, they wanted those cars. Manufacturers listened.

Today, more than two decades after Kevin Dubois immersed himself in Gran Turismo as a teen, he is immersed in the real things. His business, Evolution Dynamics in Lewisville, Texas, is a go-to shop for Evo maintenance, repair, modification, and race prep.

Customers call the shop “Evo D,” and they keep the place busy. Dubois struggles to make space to park the Evos coming in from all over the region and beyond. Evo D has built engines for customers as far away as Hawaii and Alaska, and a car even came in from Panama. The shop remotely dyno-tunes Evos over the internet and recently did so for a car in Madagascar.

Fixing and building high-performance cars for a living was not on Dubois’ radar growing up in Michigan. After earning a mechanical engineering degree from Hope College in Holland, Michigan, he landed a job with defense contractor Lockheed Martin in Texas.

“I took my hiring letter to the Mitsubishi dealer and bought a brand new 2004 Evo,” says Dubois. He coaxed more performance out of his car and then began doing the same for other Evo owners. After about six years, that side work eventually turned into the business that let him leave his day job and do Evos full-time.

Naturally, Dubois has a lot of advice for Evo newbies who should know a few things before committing to owning one of these maniacal machines.

Lancer, Evolution

The Mitsubishi Lancer Evolution was the turbocharged, all-wheel-drive tarmac terror that formed the basis for the Japanese automaker’s heroic WRC rally efforts in the 1990s. Driving Evos, Finnish driver Tommi Mäkinen won four World Rally Championships from 1996–1999, and Mitsubishi took the 1998 World Constructor’s title.

Other markets had been importing the Evo since the ’90s, but the 2003 model was the first to make it to America. It was known widely as the Evo VIII but not badged as such. The Evo IX, an upgraded version of the VIII, followed in 2006.

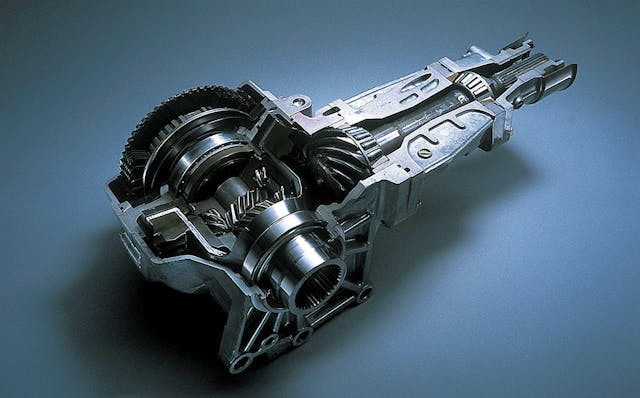

The Evo X came out for 2008 with a new platform and a new 291-horsepower aluminum 2.0-liter engine. The GSR model used a five-speed manual transmission, while the MR came exclusively with the six-speed Twin-Clutch Sportronic Shift Transmission (TC-SST, as Mitsubishi called it). The Evo X’s Super All Wheel Control system used the Active Center Differential (ACD), as on most previous Evos. The U.S. version of the Evo X also finally got the Active Yaw Control (AYC) rear-wheel torque vectoring that other markets enjoyed on earlier cars.

Mitsubishi sold just over 43,000 Evos in the U.S. through 2015, nearly half of them Evo Xs.

From garage band to center stage

While working at Lockheed Martin, Dubois was tuning 2-3 customer Evos every night out of his Texas garage. He was also studying for his Masters degree in Systems Controls at the University of Texas at Arlington, which he chose for its renowned Formula SAE program.

If you’re not familiar, Formula SAE is like a farm team for major automakers and suppliers, which hire engineers right after graduation. The schools’ teams even build 600-cc open-wheel racers and compete in their own series. Dubois was thinking of getting a job with an OEM or a supplier, such as Bosch, but the Evo work just kept growing.

“In 2005, we had the arrival of open-source software, so you could tune your Evo with a laptop,” Dubois says. “I was the first and only one in the area to take it on to tune the cars. It’s been further developed by people throughout the car community. I’ve been able to do more and more with it over the years.”

At first, Dubois was doing street tuning. He eventually rented a dyno, before going all in and buying his own. When the city forced him to stop running a business out of his garage, he rented a 1500 sq.-ft. space for his first real shop. Over the next 10 years, he’d move three times into ever-larger spaces, all on the same street in Lewisville. He is purchasing the building he’s in now.

To help handle his booming business, Dubois and a partner developed a management software specifically for high-performance shops, called My Shop Assist. He also dedicated time to developing a podcast called “Do It for A Living” to encourage others to start automotive businesses.

Factory stock? You’re kidding, right?

If you missed your chance to buy a new Evo, getting one today most likely means you’ll be getting a modified car—not lightly either.

“It’s very rare to see just basic mods like an air filter and exhaust,” Dubois says. “I almost never see totally stock Evos, but it doesn’t mean they’re not out there.”

Dubois and his long-time friend, tech Richard Fielder, work on more than 200 Evos per year, handling everything from basic maintenance to drag- and road-race builds. The shop also tackles the occasional JDM Evo, though Dubois says getting some parts for those cars can be difficult.

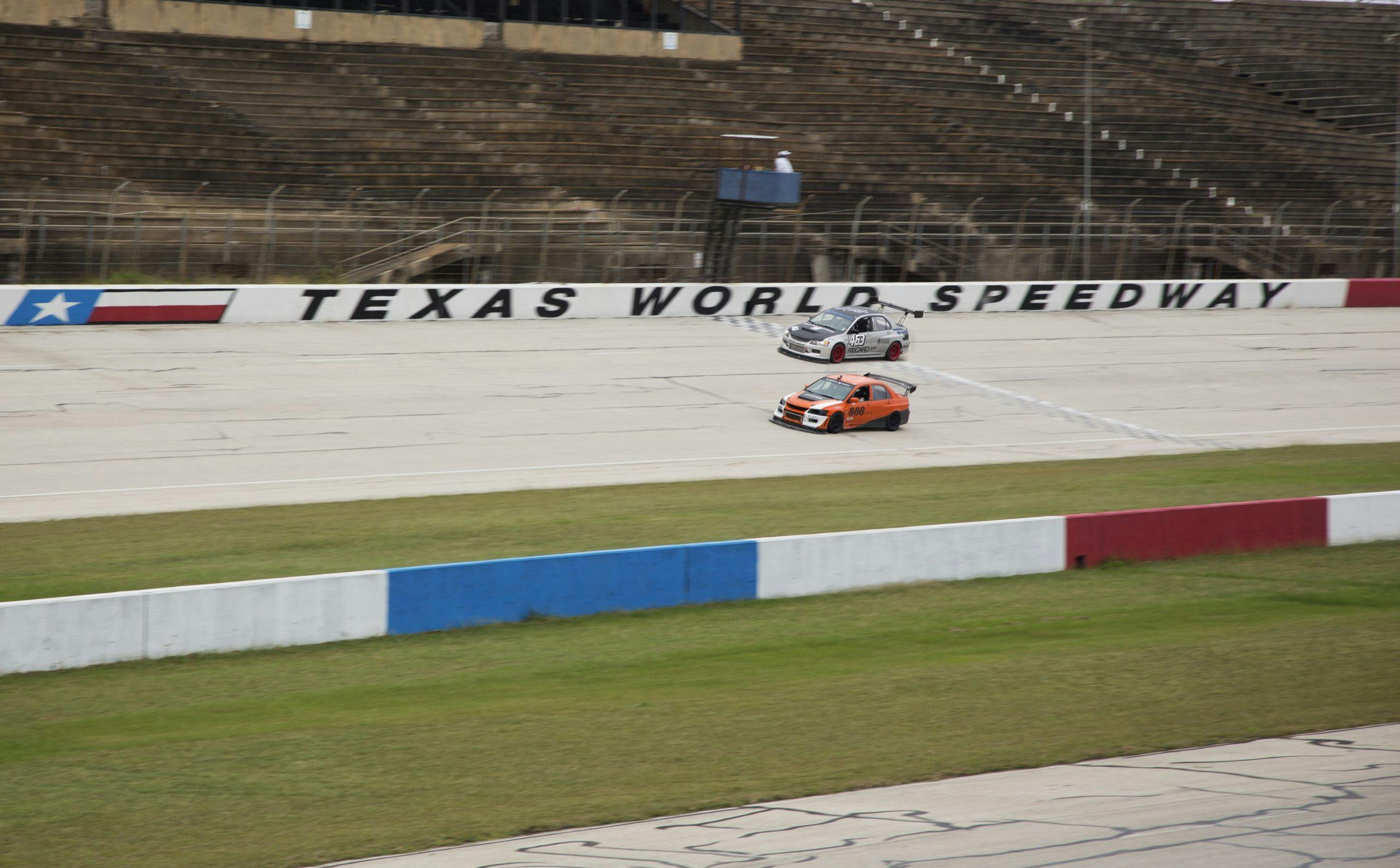

He has owned about 20 Evos since 2004, but these days Dubois buys them mainly to flip. That happened, in a literal sense, to his Evo race car. In 2012, friend and customer Jeremy Foley, with navigator Yuri Kouznetsov, drove Dubois’ highly modified Evo VIII at Pikes Peak and became famous for surviving a spectacular crash.

“After the crash, Yuri bought Jeremy’s Evo, brought it to me, and we basically made a clone of the crashed car—wide body, big wing, and painted matte silver,” says Dubois. “We took it back to Pikes Peak two years later and finished. It was basically a flawless effort.”

Kouznetsov took 37th place out of 130 finishers at the 2014 Pikes Peak International Hillclimb, with an 11:03.910 time. He still races the car in time trials.

Performance in stages

Mitsubishi dealers do still work on Evos, but local dealers refer customers to Dubois for modifications. He says he sees a range of quality in the work done at independent shops.

“It’s not a hard car to get fixed for routine things, but most shops don’t understand the specialty aspects of the car,” he says. “For example, with ‘check engine’ lights, I can figure out the problem quickly. A shop that doesn’t work on these cars may charge for several hours of diagnostics.”

Most customers with modified Evos build their cars in stages, he explains. They might start doing autocross and National Auto Sport Association (NASA) events with stock engine cars, seeking more performance down the road.

“We offer upgrades in stages, starting with the chassis,” Dubois says. “We try to keep people away from adding more speed until they can drive them better.”

He recommends lowering springs and new anti-sway bars as a good first upgrade yet also praises the stock suspension. “A lot of people think you need expensive coil-overs, but that’s not the case. We’ve done astoundingly fast lap times with stock shocks.”

Evo problem spots

Dubois pointed out the major problem areas for the Evo VIII, IX, and X. Hold onto your credit cards, because some of these are pricey.

“The cars we do are expensive enough that you don’t have the real young kids driving them, but owners do hoon them and wreck them,” he says. “It’s common for people to hurt the engine and not want to fix it. They take off the oil pan and replace a couple of bearings. Then I get the new buyer coming in hearing a tapping sound, and I have to tell him the engine needs a lot of work.”

Slipping clutches are common across the board. For the Evo VIII, Dubois says the biggest problem is the transfer case.

“The ring and pinion gears would go bad quickly and begin to howl loudly,” he says. “If you hear a humming noise when driving, it’s probably got a bad transfer case or wheel bearings, or both. The transmission synchros are also pretty crappy. Most need to be rebuilt, and that also applies to the Evo IX. They’ll grind going into third, fourth, and fifth.”

The Evo X has several potential and trouble spots, the most expensive being the TC-SST transmission in the MR model.

“The SST is not very strong and is incredibly expensive to fix,” he says, quoting a price of $8000. “I don’t rebuild them. I send them out to a couple of shops.”

The Evo X also has issues with its rear differential. “They crack, leak and burn up, and some have bad ring gears,” Dubois says, adding that the AYC pump is bad on nearly every Evo X that comes into his shop.

“And that’s just from regular driving,” he adds. “Mitsubishi didn’t do a recall but did put a 10 year/100,000-mile warranty on it.” A new AYC pump can cost about $1800 plus installation. A shop local to Dubois rebuilds them, but he says it’s hard to judge results so far.

When the Evo X came out, some questioned whether its 4B11T aluminum engine would be as robust as the iron-block 4G63 used in previous Evos. Dubois confirms that it is a durable engine. “The block is stout. It’s rare to break unless you’re running a lot of boost,” he says. He of course means a lot more than the stock engine’s 21-22 PSI of boost.

Some small parts in the Evo X motor can cause very big problems, however, starting with the iridium-tip spark plugs. “The ceramic on the tip slips down,” Dubois explains. “If you’re mashing on it when that happens, the ceramic will break, go through valves and mash up the piston tops.”

Evo X piston ring lands sometimes go bad. “I can hear the problem right away,” he says. “The car will start to sound like it’s running on three cylinders. The compression tests might not be terrible, but I can borescope it and see a broken piston or scratches on the cylinder walls.”

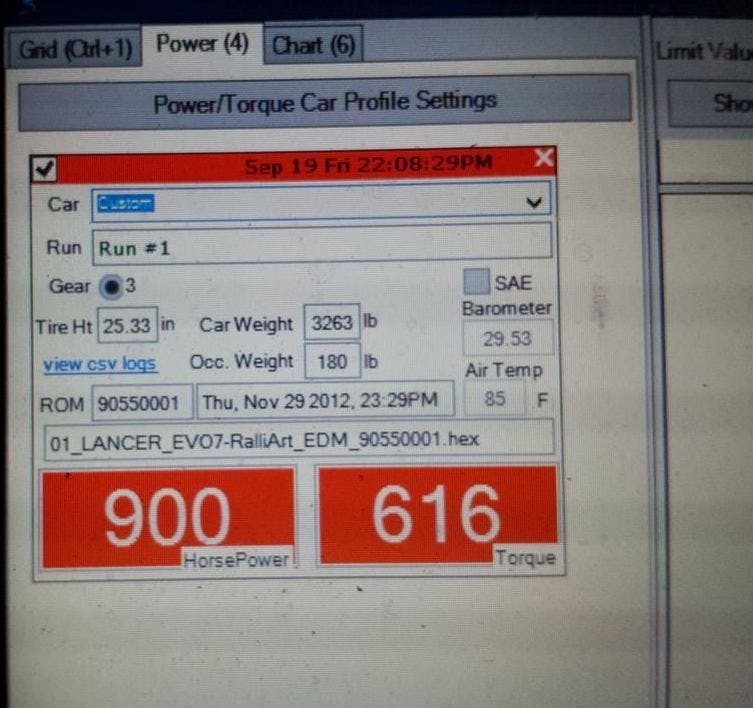

The bottom line is that the factory Evo X engines can be pushed to 500-550 hp as long as you check the spark plugs often and don’t have bad ring lands. To go higher reliably, Dubois recommends a new build, which gets into expensive territory with parts.

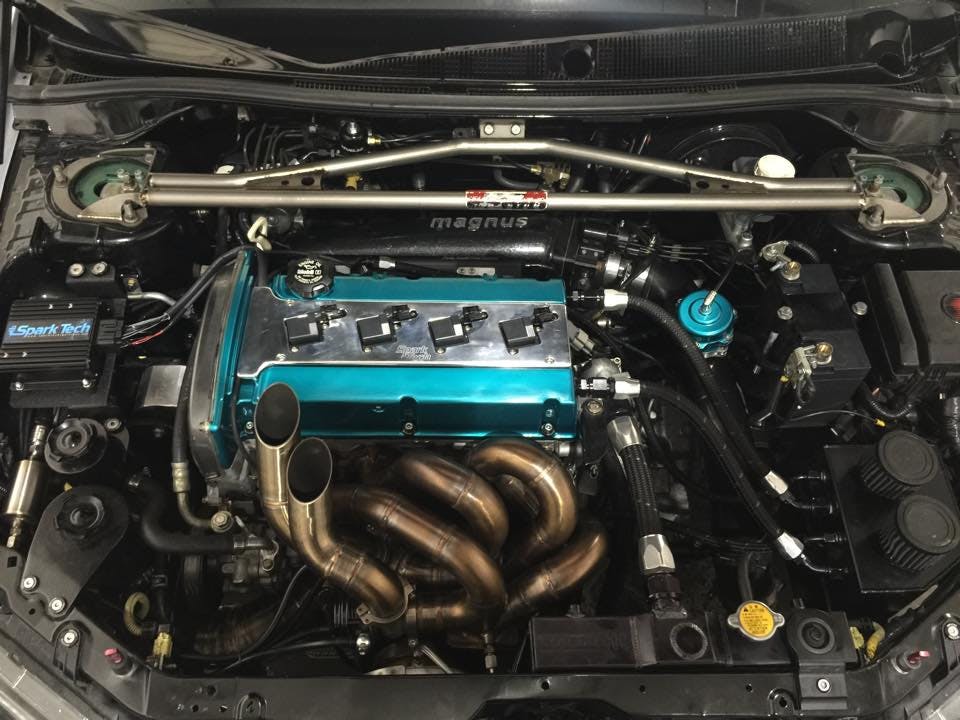

“We’ve built them to 900 hp. English Racing has gone well over 1100 horsepower with an Evo X and run a 7-second quarter mile.” (That company’s website offers drag-race crate engines for $19,990.)

Dubois confirms that Evo VIII and IX engines, too, live up to their legend, remaining “pretty indestructible to about 500 hp.”

Long live the Evo

Despite the Evo being out of production and not destined to return, Dubois feels confident in his business. “People will continue to modify, race, and break them.”

His biggest concern going forward is parts supply. Right now, he buys all stock parts from Mitsubishi dealerships, despite the markup.

“They’re simply higher quality than from parts chain stores,” he says. “Most common stuff—pistons, rods, ARP hardware—likely will be around forever. But it’s smaller stuff, like the front oil pump case, for example, that I worry about. The OEM is only one that makes that. If they drop that, you can’t rebuild the engines.”

Many enthusiasts mourned when Mitsubishi retired the amazing Evo, but it’s heartening to know that there’s still strong support from businesses like Evo D that keep these rally terrors alive and running hard.