How the 1921 Rumpler Tropfenwagen foreshadowed today’s mid-engine race cars

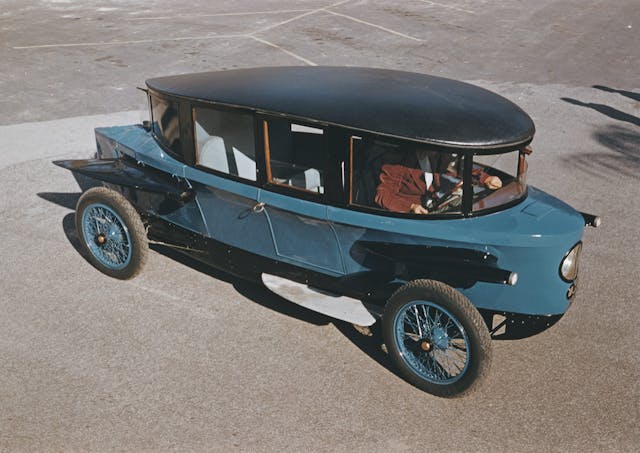

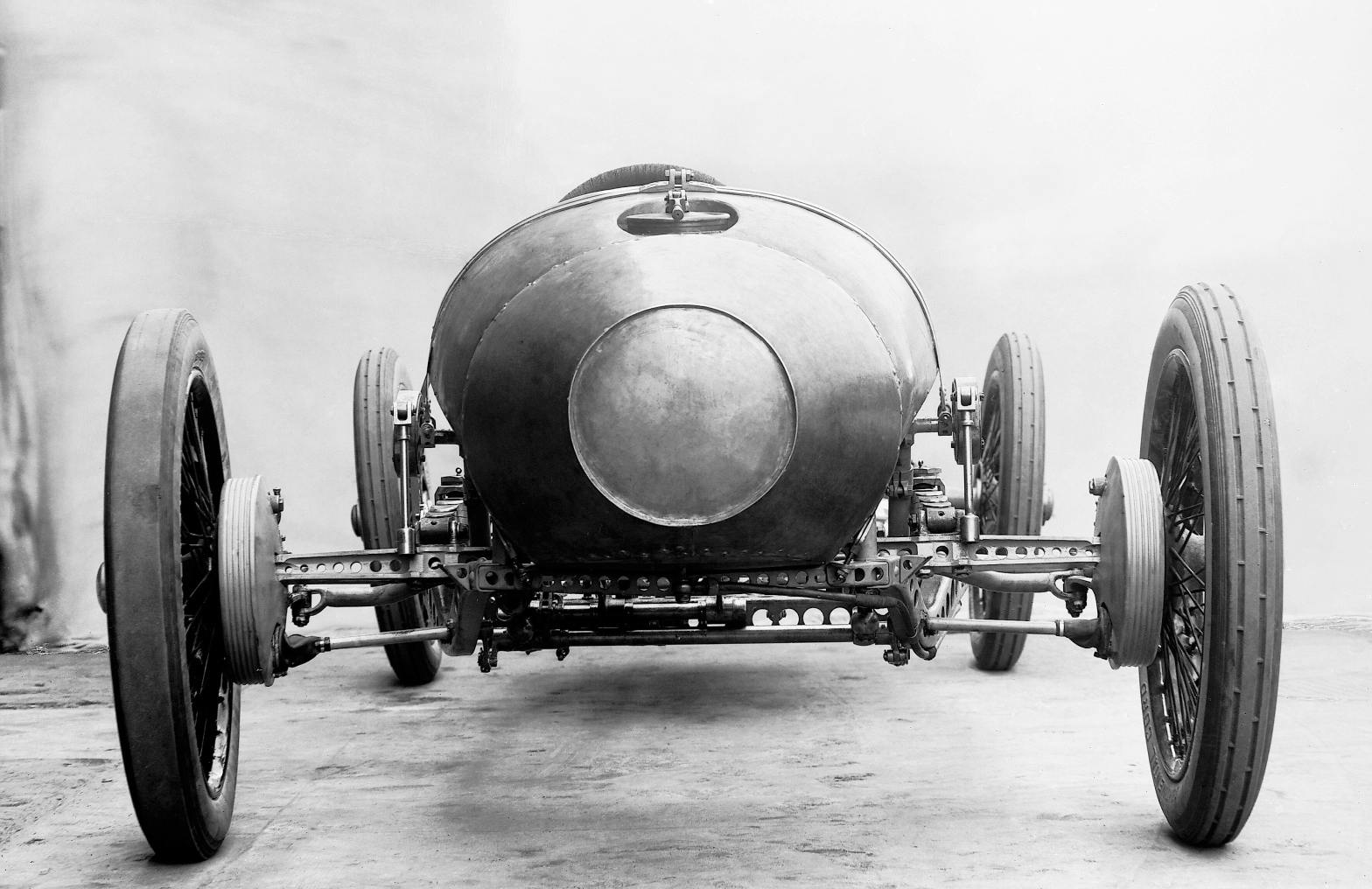

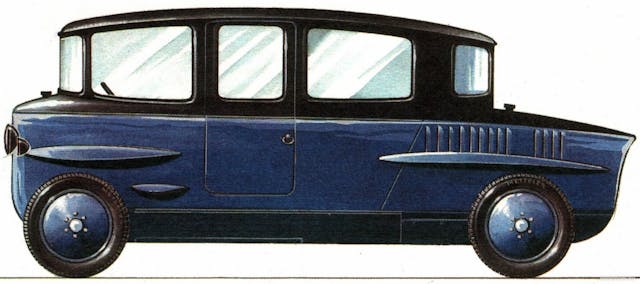

At the 1921 Berlin Motor Show, the first gathering of the car faithful following World War I, a decidedly bizarre machine wowed the crowds. Edmund Rumpler, a Vienna-born engineer who made his name as Germany’s first aircraft manufacturer, presented his Tropfenwagen (“water drop car”) with coachwork resembling a Zeppelin airship’s gondola.

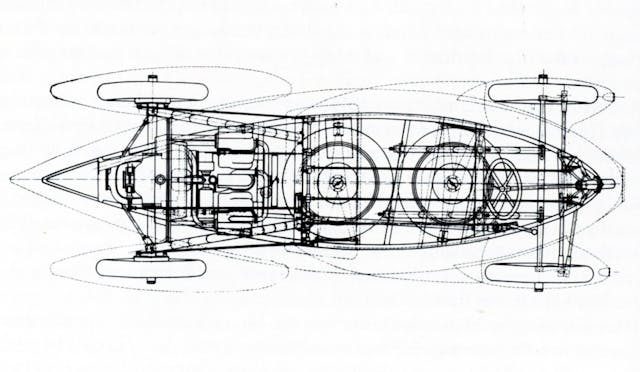

While contemporary autos were steamer-trunk boxy, Rumpler’s car was designed to gently embrace the wind. One could imagine air flowing over its airfoil-shaped roof and around its pointy nose with hardly a ruffle. In place of air-churning fenders, the Tropfenwagen had thin, horizontal slats. Its greenhouse was made of curved glass, an innovation that wouldn’t reach the automotive mainstream for decades. The wheels were smooth, flat discs.

In 1979, curious Volkswagen engineers decided to measure the drag coefficient of a Tropfenwagen residing in a German museum. To their amazement, they discovered a Cd of 0.28 (for those keeping track, that’s notably better than the 2020 Chevrolet Corvette’s 0.32 aero score).

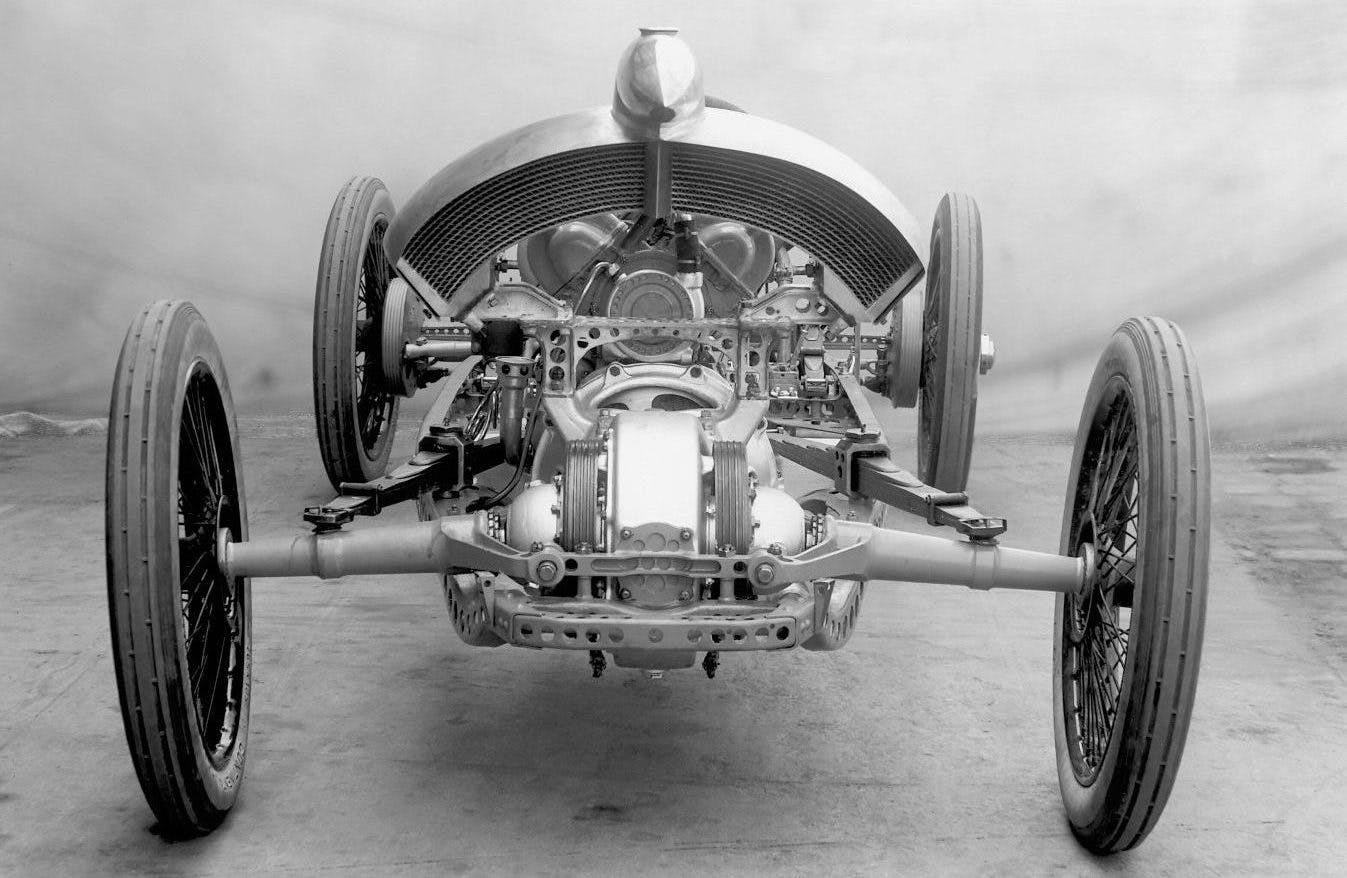

We’re celebrating the Tropfenwagen’s 99th birthday here because its genius ventures far beyond its streamlined wrappings. Rumpler located the driver dead-center for optimum forward visibility, à la the later McLaren F1. The rear wheels pivoted independently on swing axles, an arrangement Rumpler patented in 1903. While most car makers placed their engines ahead of the driver when they progressed from single- to multi-cylinder power, Rumpler stuck with a mid-mounted 2.6-liter, 36-hp W-6 engine bolted directly to a three-speed manual transaxle.

Rumpler’s bold stroke never achieved commercial success. The public didn’t know what to make of the car’s odd shape, and quality issues hampered the Tropfenwagen’s profitability. Most of the 100-or-so cars Rumpler built from 1921 through 1925 were employed as taxicabs thanks to their roomy cabins and smooth ride.

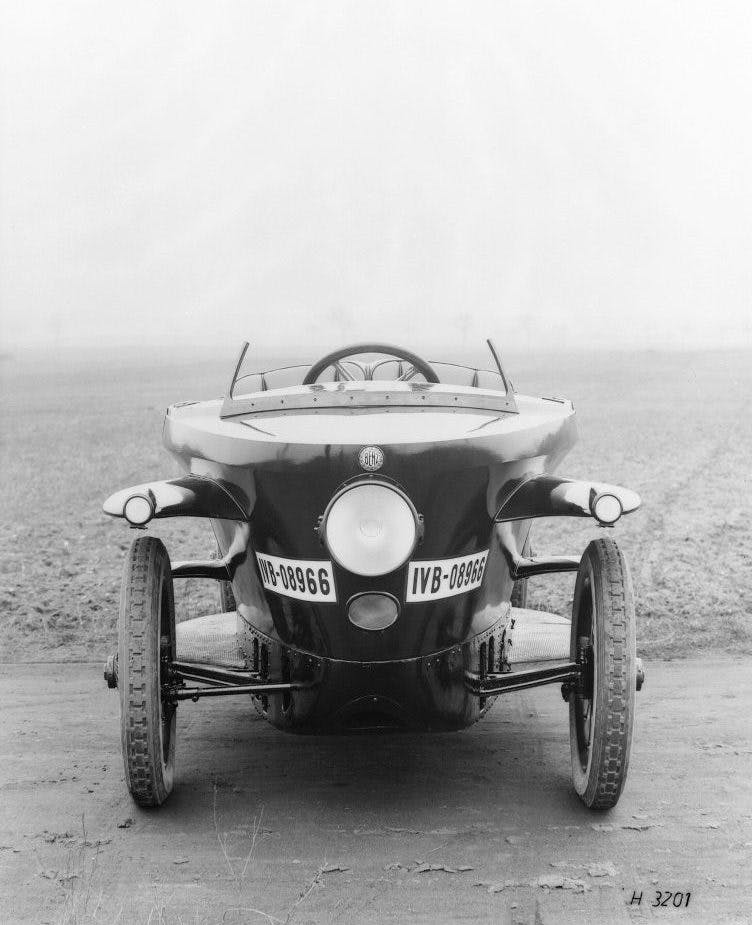

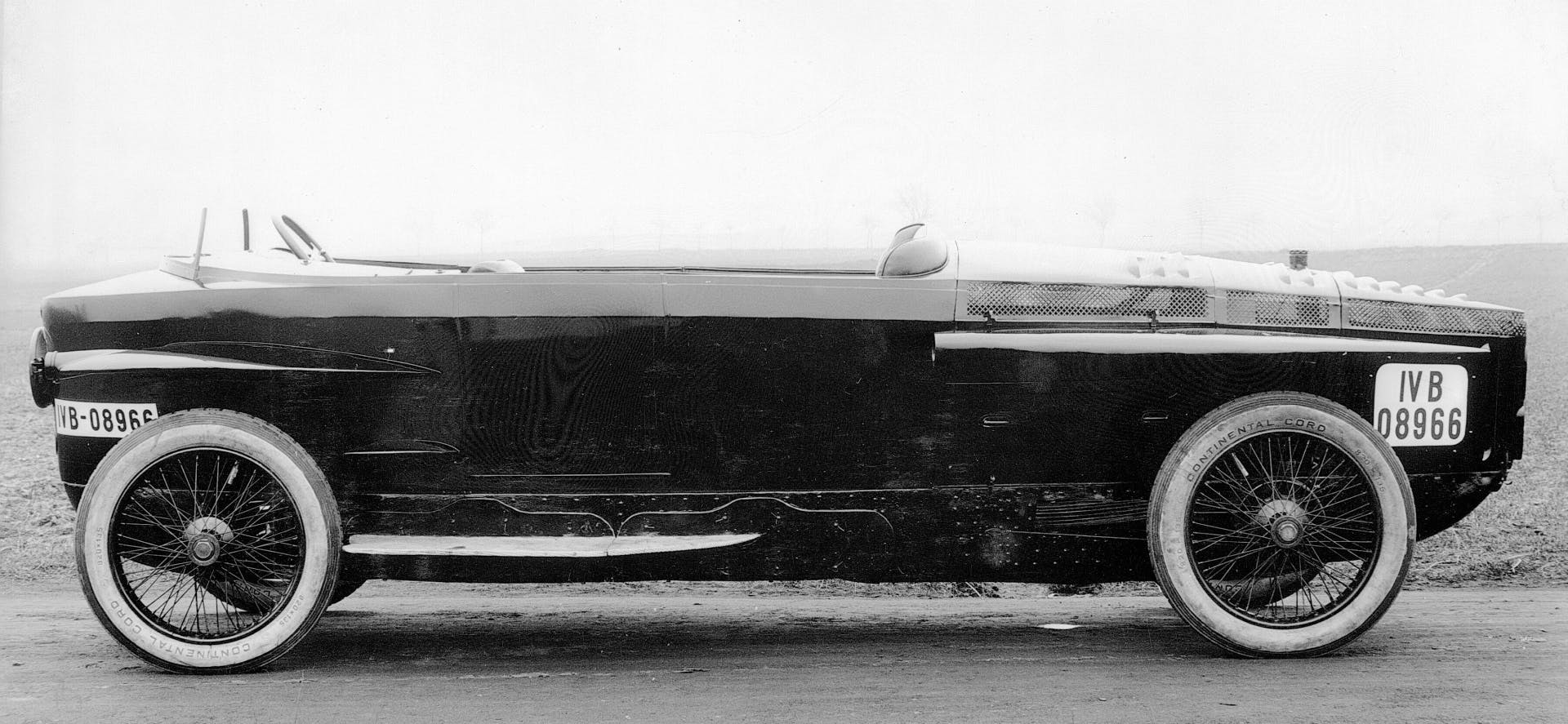

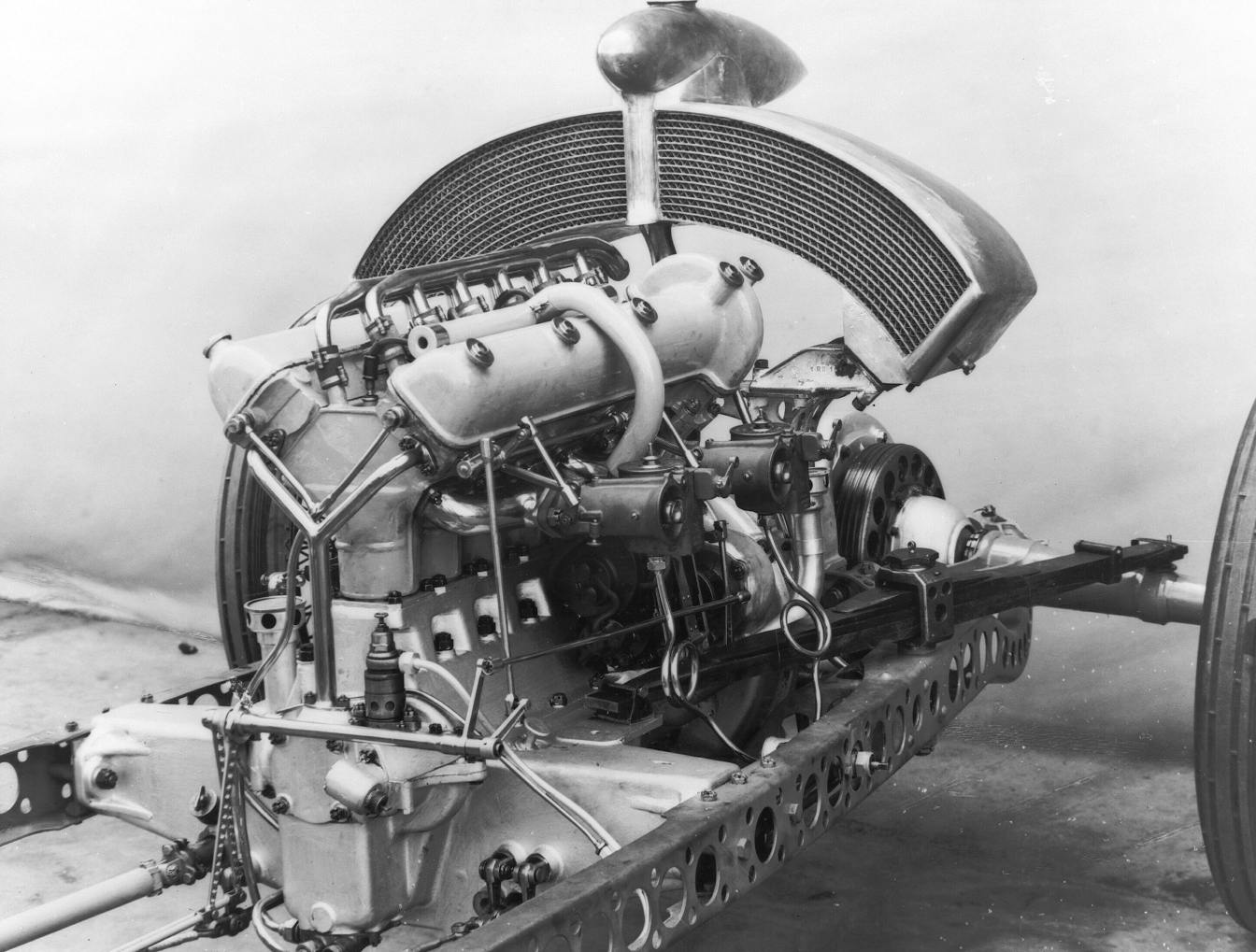

Tropfenwagen’s true legacy, however, lies in racing car design. Carl Benz’s Berlin agent Willy Walb urged his bosses to adopt Rumpler’s ideas for both Grand Prix and sports car applications. Benz’s chief engineer Hans Nibel created the Typ RH (Rennwagen mit heckmotor or “rear-engined race car”) to campaign in the 1923 season. A 2.0-liter DOHC inline-six mounted just behind the driver delivered 90 hp to a four-speed transaxle, yielding a top speed of 115 mph.

Of the three RHs entered in the Grand Prix of Europe at Monza, two snagged fourth- and fifth-place finishes. While the wily Benzes demonstrated excellent handling, they lacked the power of the supercharged Fiats which finished first and second. Drivers Walb and Adolf Rosenberger also drove RHs in local German events, earning a win at the 1925 Solitude road race near Stuttgart.

In 1930, Walb and Rosenberger joined forces at Ferdinand Porsche’s Stuttgart design house. There they convinced Dr. Porsche to spot his remarkable V-16 engines in the middle of the car, a strategy that allowed Auto Union to win their share of Grand Prix races from 1934–39.

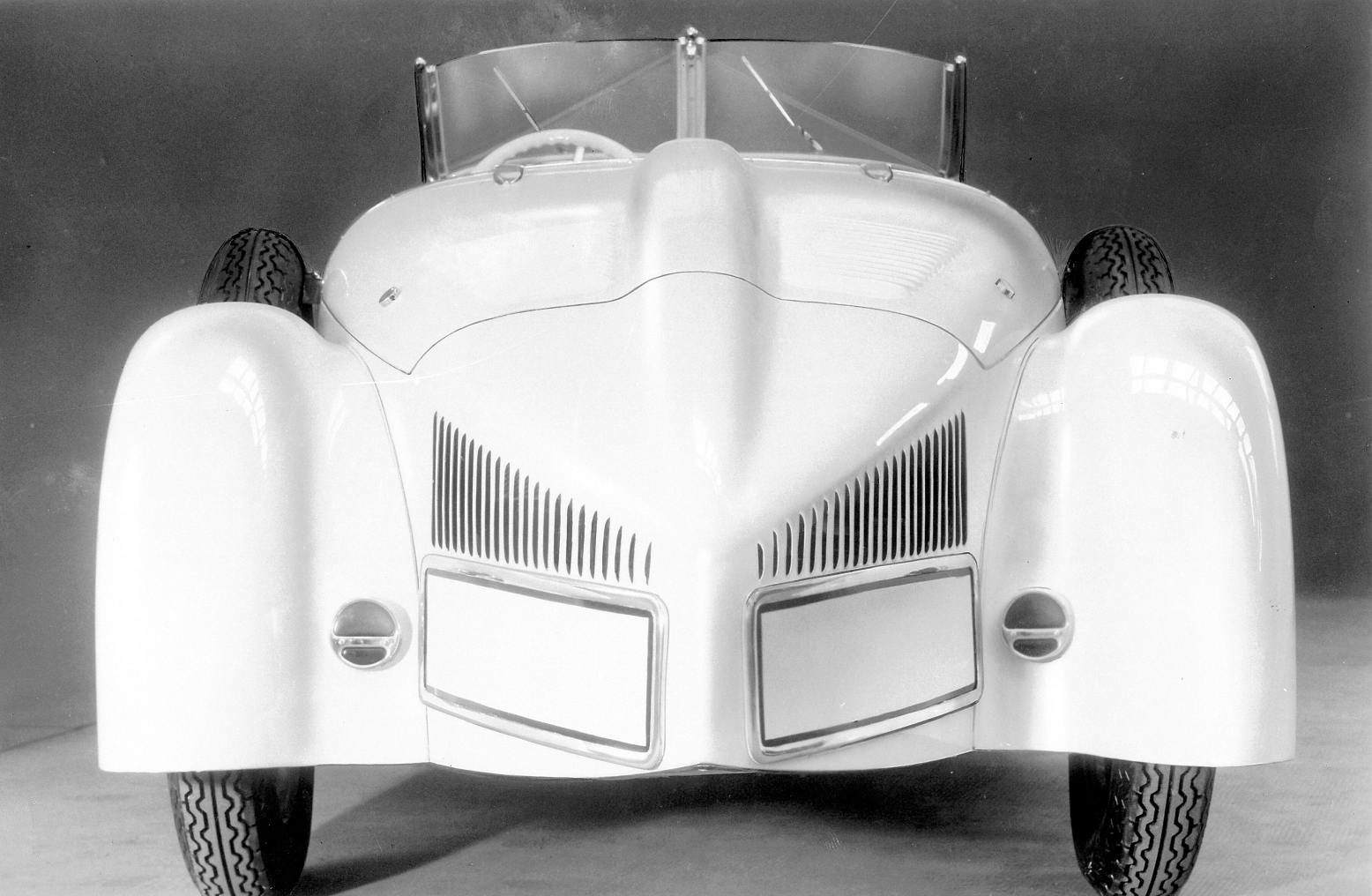

A decade after Mercedes (Daimler) and Benz merged, lessons learned from the Benz RH were invested in a run of two-seat 150H roadsters powered by a 1.5-liter SOHC inline-four located just behind the cockpit. Twenty such cars plus five coupes were built and sold from 1934 through 1936. In essence, they were accurate previews of today’s sports cars. The program ceased only because Mercedes chose the front-engine alternative for its 1930s-era Grand Prix cars. Worried about confusing its production car customers with competing powertrain layouts, Mercedes focused solely on front-engine designs.

After World War II, John Cooper resurrected the mid-engine layout for his 500cc racers powered by motorcycle engines. Ferry Porsche’s successful 550 sports car arrived in 1953 followed by BRM and Lotus Formula One racers in 1960. Jack Brabham’s ninth-place finish at the 1961 Indy 500 in a svelte mid-engine Cooper Climax was instrumental in sending the classic Indy roadster the way of the buggy whip. By the end of the decade, the entire Brickyard field was mid-engine.

In the road-going realm, Lamborghini’s V-12 Miura introduced in 1966 is widely regarded as the seminal supercar thanks to its combination of exotic exterior design, mid-engine layout, and spectacular performance. Pontiac’s humble Fiero sold in the mid-1980s brought the idea to the American masses.

While front-engine sports cars are clearly not obsolete, no contemporary race car designer would adopt that arrangement when the rules allow a mid-mounted layout. You can thank Edmund Rumpler for inventing the way forward nearly a century ago.