Tracing Koenigsegg’s 25-year history through a lost scale model, reclaimed on eBay

Koenigsegg’s 25th anniversary was in 2019. Even for a young brand with relatively little history, the brand’s engineering legacy deserves a holistic deep-dive into archives and a full examination of the company’s earliest days. We wish that were possible. However, in 2003, the thatched roof of the historic building that used to be Koenigsegg’s Margretetorp, Sweden, factory went ablaze, just two weeks before the CC8S was set to debut at the Geneva Motor Show. Christian von Koenigsegg’s childhood drawings, early sketches, and floppy discs containing files made using Microsoft Paint were lost.

Files like this one. Not all, evidently, disappeared.

Fortunately, the fire did not destroy Koenigsegg’s original clay scale model built in early 1994. That’s because the model mysteriously vanished six years before the factory catastrophe, in 1997. It was one of the earliest representations of Koenigsegg’s design vision—an irreplaceable relic of the brand’s foundation.

Prototype powerplants

In those early days, Koenigsegg knew what his supercar might look like, so the next step was to figure out what he’d use to power it. The Koenigsegg brand is well known today for using an engine of its own design, but the first CC prototype built between 1994 and 1996 used a 4.2-liter Audi V-8. (Yes, the same one that Lamborghini wanted to use in 1998, just before Audi decided otherwise.) In the end, though, Christian von Koenigsegg couldn’t cut an engine supply deal with Audi because he wanted more power, and Ingolstadt wouldn’t support aftermarket tuning. Here’s how Christian von Koenigsegg remembers it:

“I didn’t have the ambition at that time for us to build our own engine from scratch, though I didn’t want to just have a standard Audi V-8, either. I wanted to tune it, to take it to 550-600 hp. So I went to Audi and I said “Hi, I’m Christian and I’m going to build sports cars. Can you supply me with engines?” and they were surprisingly positive about it—until I mentioned that I was going to tune it.

We had a lot of discussions back and forth and they were interested in doing business, but they weren’t interested in their engines being tuned by others. We almost found a back-channel through an industry supplier in Denmark and we even signed an engine supply contract thinking that we’d be OK buying them this way, but Audi heard about it and shut that avenue down, too. So we had this prototype, based around a particular setup that we thought we could use and we had no engine supplier. We could have sued but I didn’t want to go down that path.”

Then came the idea of using the Motori Moderni Subaru flat-12 designed by Carlo Chiti for Minardi in Formula 1. This engine didn’t make it big in racing, but it had potential for sure, according to Christian von Koenigsegg:

“The 12-cylinder engine wasn’t successful in Formula 1 but Motori Moderni had great success building other engines for Alfa Romeo to use in DTM racing. They had proven their worth, so they were worth talking to. We went and met with them and they were very open. They said they could modify their 3.5-liter flat-twelve engine for us. Similar engines had been used in offshore boat racing with twin turbos on them, so we were confident enough in their durability. They put together a 3.8-liter flat-twelve and they lowered the rpm from 12,000 to 9000. They put different camshafts on it, they stroked it, put in longer intake tracts. It was set up to get 580 hp at 9000 rpm and I have the dyno tests from where we ran that engine.”

What about Koenigsegg vehicles using a Koenig Competition-like powertrain instead of the twin-supercharged and twin-turbocharged V-8s that made it into production? Well, Christian von Koenigsegg went about as far with that idea as he could:

“When we first designed the Koenigsegg monocoque, it was designed for that engine and it was the first engine we put in there. The engine mount positions for that engine were still used in the Agera. Unfortunately, around this time, Carlo Chiti died and the company filed for bankruptcy. We had received two engines from them (which we still have) but once again, we found ourselves with no engine supplier.

In early 1997, I ended up winning an auction to buy some of the company’s assets. I got all the tools, the drawings, the castings and some spare parts for the engines. We thought that maybe, with all that equipment, we could build our own engines from Chiti’s designs but when we got the equipment back to Sweden and started sorting it all out, it was a nightmare. There we no computerized drawings. It was all drawn by hand. A lot of the tooling was old and made from wood and it was quite beaten up.

Would the engine have been viable for the future? Certainly at first. It was quite amazing, actually. The whole engine block was under the center of the rear axle, which gave us a super-low centre of gravity and looked very cool when you opened the rear hood of the car. There was no vibration whatsoever, which is why we decided to bolt it to the monocoque—it was wide, low, and solid, so it acted just like a chassis member. We still do that with the V-8’s we use today but with a tiny compromise because they’re not as smooth.”

Last but not least, this Subaru-based flat-twelve wouldn’t take more than roughly 700 horsepower, regardless of the turbo setup. It was just a dead end.

From scale model to prototype

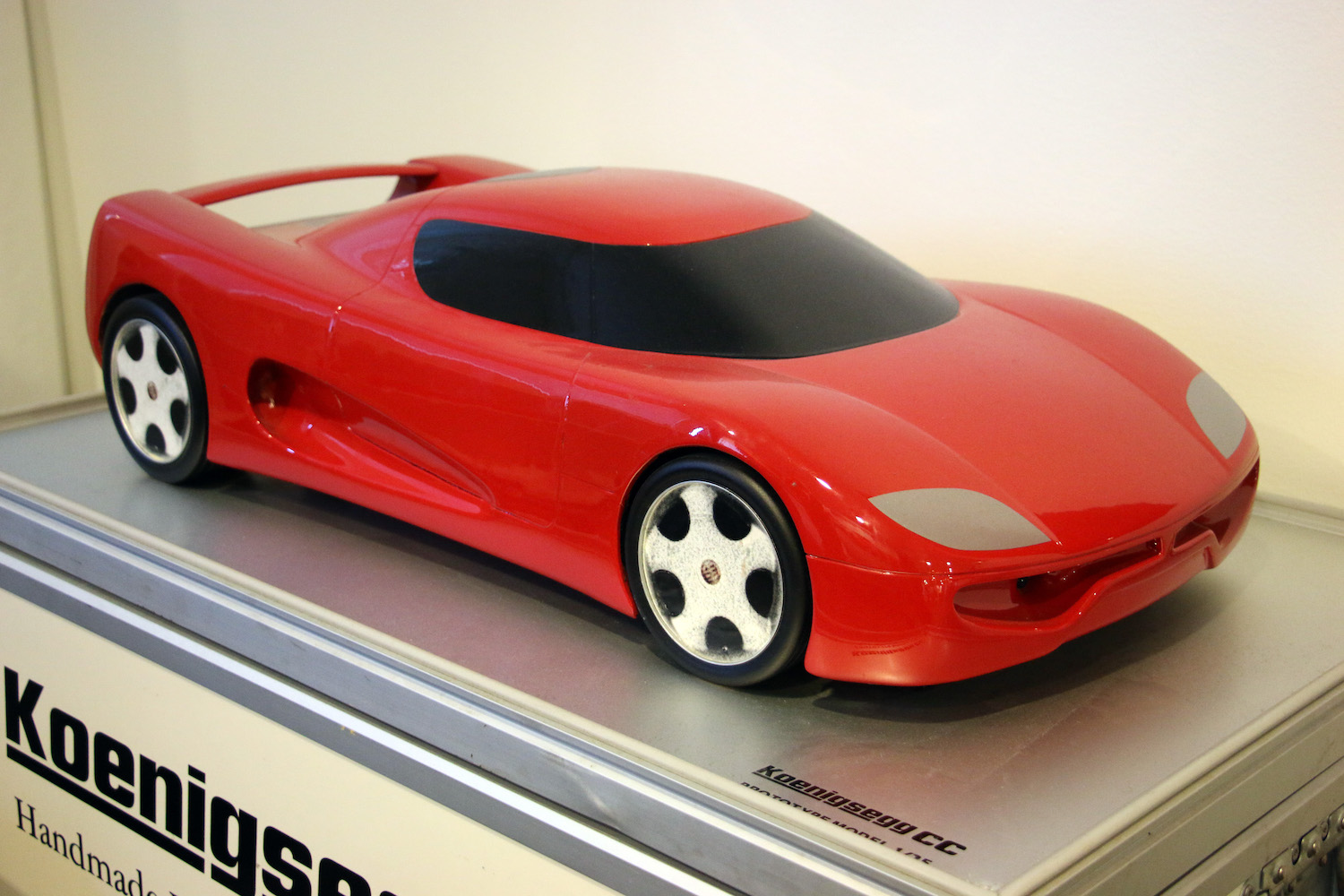

Whether it was Audi V-8 or Moderni flat-twelve, Koenigsegg just wanted to see his CC prototype in motion by 1995. Christian von Koenigsegg’s initial design already included such exterior features as the wrap-around windscreen, short overhangs, and the detachable hardtop. These drawings were turned into three dimensions in the form of a 1:5-scale, red-painted clay model made by David Crafoord, a childhood friend of Christian’s former business partner Michael Bergfelt.

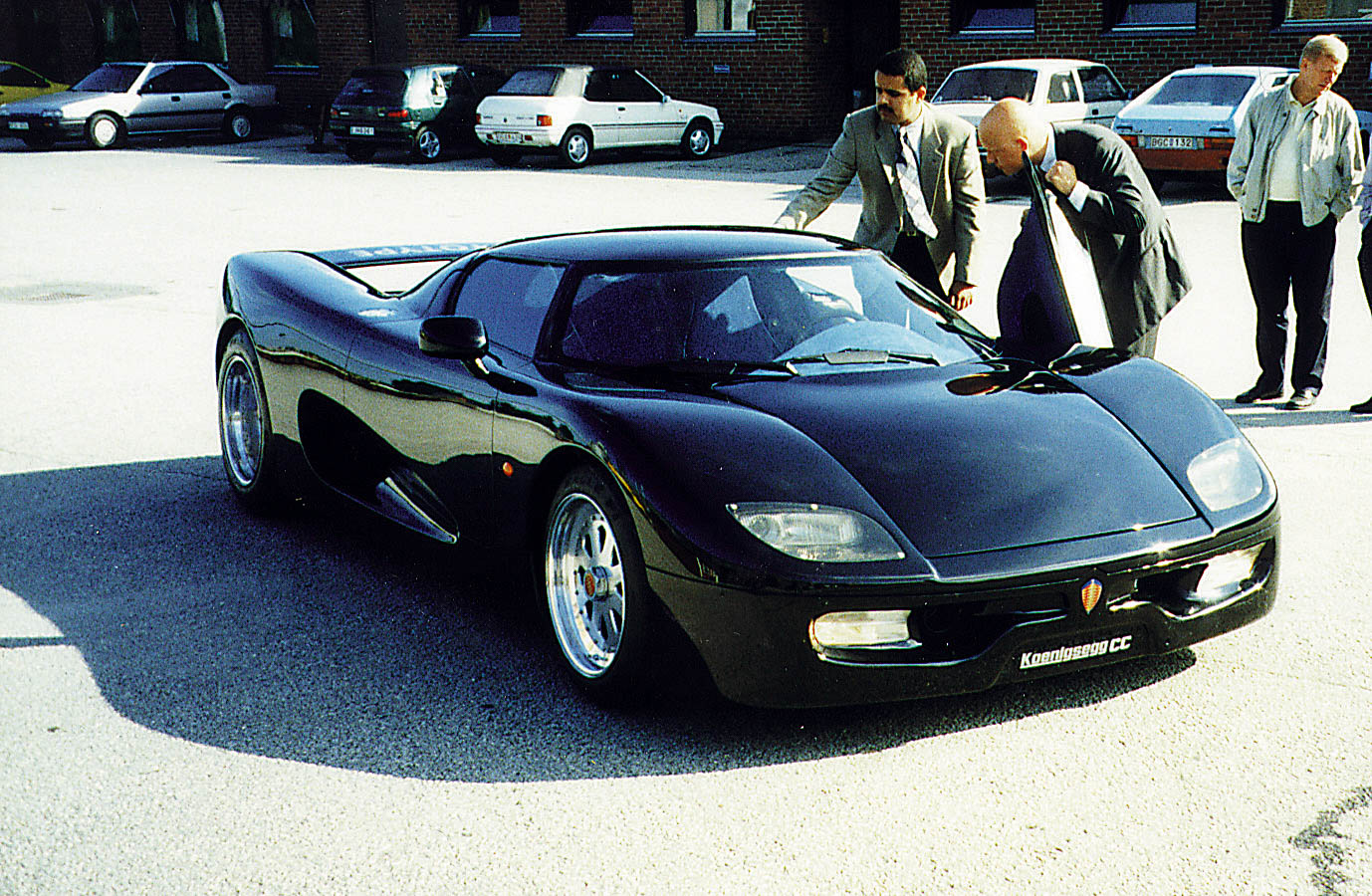

The problem? Koenigsegg wasn’t satisfied with how his contractor built up the prototype from the initial scale model. In the end, the full-size car had to be extensively modified before its delayed debut at the Anderstorp Raceway in 1996. This CC prototype featured the Audi drivetrain, a full composite body painted silver, three-piece BBS wheels, and for the time being, traditional doors.

Getting to this point had been, as you might imagine, expensive. When the Jesko was launched in 2019, Koenigsegg told the story of how his parents sold their apartment in Stockholm to help finance his business. Yet even more clever decisions had to be made long before that:

“I had a pretty simple business plan—I would find out what people needed, I would find that stuff for a cheap price and then I would sell it. It was the early 1990s and the Iron Curtain had just fallen. There were plenty of people who needed things, stuff as simple as pens or plastic bags. I found a big batch of plastic bags that had been printed with a logo the wrong way, for example. They were going to be thrown out. I bought them and sold them into Eastern Europe. They didn’t care about the logo. They just needed the bags. I sold frozen chickens from the USA into Estonia. Whatever people needed that I could find at a good price, I sold, and it turned into a good business. It wasn’t a business that I was passionate about at all, but it worked and it made me enough money to get started with my real dream… building cars.”

Think about that for a second. You want to make your own car. Not just that, but you want to make the best supercar. And you have a fairly good idea what that should look like, but unlike young Horacio Pagani, you haven’t worked your way up at Lamborghini, you don’t live in Modena, and frankly, your country is more used to building fighter jets than supercars. A tough start, but what’s for sure is that you’ll need money. A lot of cash, because there’s rent, tooling, contractors, and at the end of the day, you need to come up with a prototype as soon as possible that will convince investors and grant you funding for homologation and going into production. So, to get there, you ship frozen chickens from the U.S. to Estonia? Why? Because it’s a good deal, and Tallinn, the capital of Estonia, is only 236 miles from Stockholm.

Frozen chickens aside, the Swedish government also had a program that would lend money to technology-based start-up companies. Koenigsegg got roughly $280,000 in Swedish kronas, on the condition that the company would move to an area with high unemployment. Instead of heading north above the Arctic Circle, Koenigsegg chose southeast Sweden, a place called Olofström, where Volvo also had a presence. Unfortunately, that renting deal fell through when Volvo took over the area Koenigsegg was supposed to have, and so the factory moved to Margretetorp, just north of today’s base at Ängelholm.

Disappearing act

Once an early version of Koenigsegg’s unique dihedral synchro-helix door mechanism had been fitted to the CC prototype, the car required respraying to hide some scars. It went from silver to black at first, but that wasn’t the end of it; the team soon realized that black was too hard to keep clean enough to promote an ambitious startup company.

It was 1997. While the resprayed CC mule was making the rounds in Europe, Koenigsegg also sent the original red scale model on a global tour to woo potential investors and customers. It was shielded in transit with a sturdy protective box, but both the model and the box nonetheless went missing somewhere in the U.S. Gone—just like that.

History ablaze

After the CC mule was once again repainted, this time in a weird metallic brown color (despite Christian von Koenigsegg asking for Volvo’s orange over the phone), the team began to work on its first pre-production show car—the CC8S. It was set for a grand debut at the 2000 Paris Motor Show.

Powered by a heavily modified and supercharged Ford V-8 tuned to produce 655 horsepower, the CC8S was finally the real deal. Koenigsegg went on to produce six units over two years, with two built in right-hand drive configuration. Things were looking promising.

Then, two weeks before Koenigsegg’s first customer production car would wow the crowds of the 2003 Geneva Motor Show, disaster struck.

In February 2003, the thatched roof of the Koenigsegg factory at Margretetorp caught fire. It was a Saturday, and while the cars and the tooling were saved by the staff on site, some of Carlo Chiti’s flat-12 blueprints, as well as almost all of Christian von Koenigsegg’s childhood sketches and early company records were lost. Thankfully, the CC8S’ production could continue to keep the business afloat, but the archives were ash.

The now-brown-ish CC prototype ended up in the collection of the Motala Motormuseum about 120 miles southwest of Stockholm—but with so much lost in the fire, the original, one-of-a-kind clay scale model lost in the U.S. was a critical piece of the Koenigsegg archival puzzle that remained dearly missing.

A bid to reclaim history

And then, in 2007, an Internet miracle. The lost scale model popped up on eBay, still located in the United States. Given that it was one of the last remaining physical relics of Koenigsegg’s origins, the company made sure it won the auction. The model was soon on its way home to Sweden.

When Christian von Koenigsegg opened the container, he was surprised to see that it was completely intact. Surely the result of the insulated box that survived, the model bore no cracks, no fading, just the original CC design in its purest form.

In such perfect condition, the scale model was ready to be displayed at Koenigsegg’s showroom at Ängelholm, not far from the twin-supercharged 2004 Koenigsegg CCR (finished in that Volvo shade of orange Koenigsegg wanted to see on the original CC prototype).

Now, a quarter-century after Koenigsegg was founded, that red scale model is a salient reminder of the brand’s turbulent first decade.