Austria’s Magna-Steyr museum is full of strange, forgotten, and fantastic treasures

On paper, the Mercedes-Benz G-Class and the Jaguar I-Pace have as much in common as an oak tree and a cactus. They move people from point A to point B, but they’re two completely different answers to the same question. And yet, each traces its roots to the same company based in Graz, Austria.

Magna-Steyr (formerly Steyr-Daimler-Puch) has spent decades developing and manufacturing cars for other automakers. It has also produced its own vehicles, either after designing them in-house or purchasing a license from the firm that created them. It remains one of the underappreciated companies in the automotive industry; many motorists rely on Steyr’s technology every day without knowing it’s there, and the museum is just as inconspicuous.

Housed in a low-key warehouse on the north side of Graz, the collection is made up of dusty, leaky, and generally neglected-looking production models, could-have-beens, should-have-beens, one-offs, and b-sides. It’s unlike any museum I’ve ever seen, and it’s fascinating to walk through. Don’t expect photogenic displays and a café selling Puch logo-shaped cookies. This is straight, unfiltered automotive history for the nerdiest of the nerds. I loved it.

Here are some of the highlights from a recent visit.

Steyr Type 50 (1936)

The Steyr Type 50 could have competed directly against the Volkswagen Beetle. It looks like a Beetle viewed through the wrong end of a telescope, but the two cars share no components and they have no common heritage. The Type 50 was designed in-house by Steyr starting in 1934, and it was considerably more advanced than its would-be competitor.

Built using unibody construction, the Type 50 featured a water-cooled, 978-cc four-cylinder engine that delivered 22 horsepower at 3800 rpm. It could carry four passengers at 55 mph.

Like the Beetle, the Type 50 was envisioned as a people’s car: cheap to build, buy, and drive on a daily basis; and easy to repair. Steyr never planned to bring the model to production on its own. Instead, they hoped to sell the basic design to a manufacturer or government looking for a fast, relatively affordable, turn-key way enter the segment.

In hindsight, the Type 50 was born at the wrong time. In the late 1930s, car manufacturers put their expansion plans on hiatus as Europe spiraled into World War II. The Type 50 remained available when the war ended, but it was far less appealing because by then it was over a decade old. The Type 50 remained a prototype—a common theme in this museum.

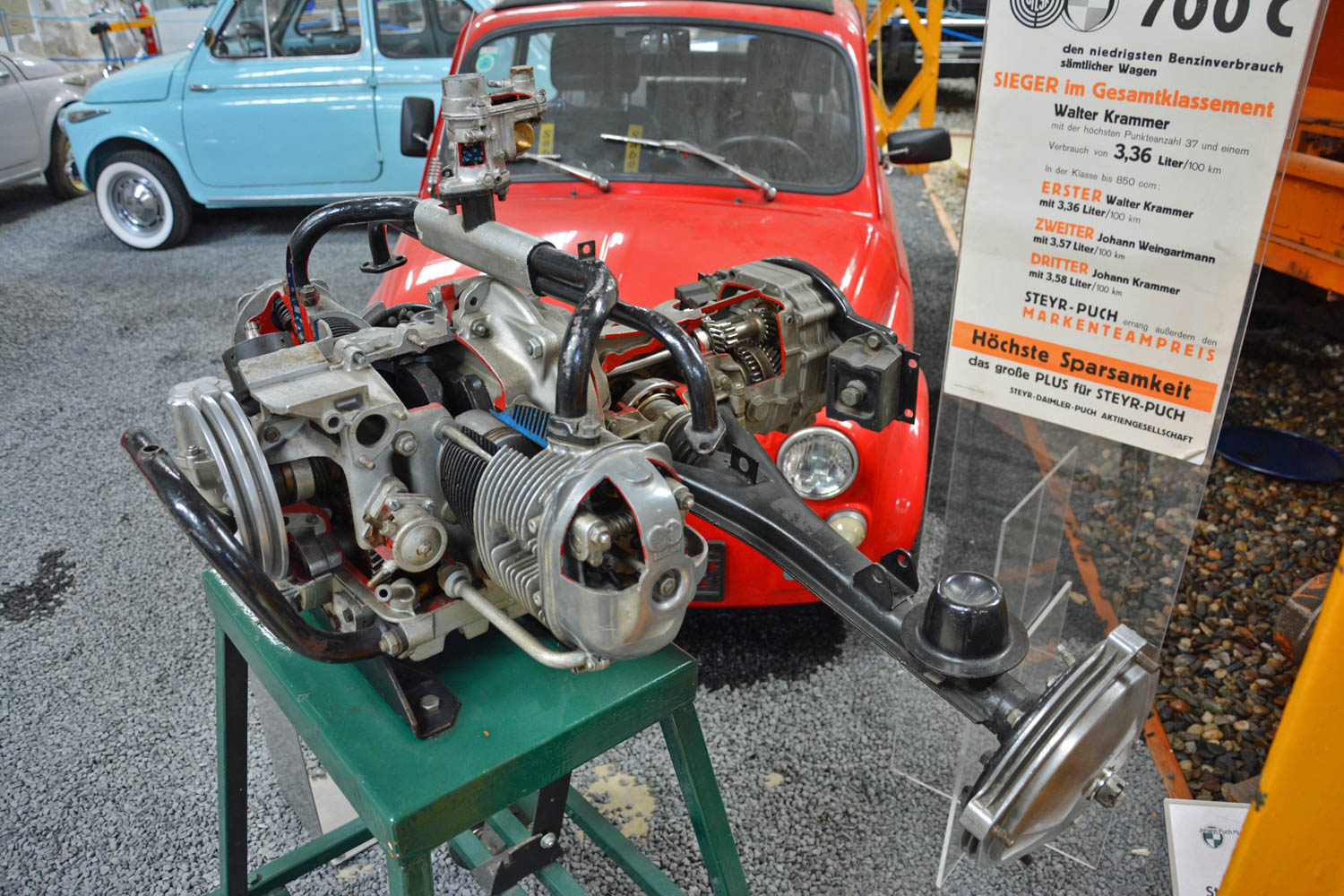

Steyr-Puch 500 (1957)

Before World War II, Steyr developed and built the Type 50 to form a partnership with an automaker seeking a people’s car. Despite good initial prospects, the tables turned on the Type 50 during the war. In the 1950s, the firm found itself searching for an economy car to build in Graz and sell locally. Turin-based Fiat heard the call from across the Alps and wasted no time answering.

At the time, Fiat was willing to license its products to anyone who could afford to pay for them. Fiat sold Steyr the right to build the tiny, rear-engined 500, an entry-level model released in the summer of 1957. However, the Austrians took it for a quick spin and found several areas that needed improvement.

The Fiat 500 launched in Italy with an air-cooled, 479-cc straight-two engine rated at merely 13.5 horsepower. Steyr replaced it with a 493-cc flat-twin tuned to 16 horsepower and bolted to a fully synchronized four-speed manual transmission. This combination made driving the 500 in the Alps far less of a chore.

Graz-built 500s featured several visual tweaks, including a brand-specific front end, bigger rear lights fitted to some variants, and a redesigned engine lid with lower, wider air vents. Steyr also offered the 500 with a full metal roof; Austrians commuting to work in the middle of winter presumably didn’t appreciate the luxury of a sunroof.

Like Fiat, Steyr made the 500 between 1957 and 1975. Steyr’s 500 sold 60,000 examples, mostly on the Austrian market.

Puch Roadster S prototype (1959)

As the 1960s approached, the 500’s success encouraged Steyr to explore the feasibility of creating an entire line-up of small, relatively affordable economy cars. The star of the portfolio could have been a two-seater convertible developed with an eye on performance; think of it as an Alfa Romeo Giulietta Spider for buyers on a budget.

Engineers deemed the 500’s flat-twin too gutless to power the roadster, so they fused two of them together to create an air-cooled, 985-cc flat-four. The rear-mounted unit sent 45 horsepower to the rear wheels in its most basic configuration, though later prototypes received a 1.3-liter with 56 horsepower on tap. Steyr installed drum brakes from the Haflinger to keep development costs in check.

Italian coachbuilder Vignale designed and built a gorgeous body that would have looked right at home in a Fiat brochure. The Puch Roadster S could have become one of the most collectible cars ever to come out of Austria, but it remained at the prototype stage for reasons that remain murky.

Steyr-Puch’s sportier 500s (1964)

Austrian motorists zig-zagging across the Alps in Steyr’s pocket-sized 500 quickly concluded the model would be a blast to drive if the accelerator pedal unlocked more power. Steyr developed a 643-cc evolution of its flat-twin that made up to 25 horsepower and installed it in the wagon model based on the 500 Giardiniera. This family-friendly model wasn’t exactly sporty, though.

The process of unleashing the 500’s performance potential began in 1962 when Steyr installed the 20-horsepower version of the wagon’s 643-cc engine in the standard 500. Called 650 T, it became a common sight at motorsport events held in Austria. The 650 TR launched in 1964 benefitted from a 660-cc engine with 27 horsepower, while the 650 TR II released the following year pushed the performance envelope further thanks to a 41-horsepower evolution of the twin.

The humble 500 had morphed into a true high-performance machine. The TRs elbowed their way into FIA-sanctioned Group II events around Europe; Polish driver Sobiesław Zasada notably raced a 650 TR in the 1965 Monte Carlo Rally, and he won the 1966 European Rally Championship in a nearly identical car.

In 2019, the sporty variants of Puch’s 500 remain popular in historic races, including hill climbs. They’re also a relatively common sight during the Historic Monte-Carlo Rally.

Mercedes-Benz/Puch G-Class (1979)

Mercedes-Benz and Steyr began working on the G-Class project in 1972. Both companies needed the model. Mercedes wanted to offer an alternative to the Land Rover widely used in rural and mountainous parts of Europe. Steyr sought a more civilized replacement for the Haflinger—the G was code-named H2 (Haflinger 2) internally during its development phase.

The two partners ultimately agreed on several key points. First, the G needed to look current for at least a decade. Second, it had to be exceptionally capable off-road. Third, they wanted an off-roader that was easy to build and easy to repair with only basic tools. These requirements played a significant part in shaping the G, literally and figuratively.

Steyr and Mercedes knew the G would need to fill many roles. They consequently experimented with several variants, including a four-door soft top that never reached production.

Mercedes released the G-Class in dozens of global markets in 1979. However, the off-roader was sold with a Puch emblem in Austria, Switzerland, and select Eastern European countries. Puch’s variant of the G was identical to the Mercedes-badged model save for brand-specific emblems.

In 2019, Magna-Steyr builds the current-generation G-Class, but there is no longer a Puch-badged alternative made for the local market.

Volkswagen T3 Syncro (1984)

Several Volkswagen engineers developed and tested a four-wheel drive bay-window Bus during the late 1970s, but the drivetrain never reached mass production. Instead of using in-house technology, executives solicited Steyr’s help to design and build the Syncro system made available on the Vanagon and its derivatives between 1984–1992. The flat-four spun the rear wheels in normal driving conditions; its power traveled to the front wheels if the back axle lost grip.

Steyr helped Volkswagen launch its first mass-produced four-wheel drive van, but its contribution to the Vanagon’s career wasn’t limited to the Syncro system. It took over production of the two-wheel drive model in the spring of 1990 because Volkswagen needed the production capacity in its Hanover, Germany, facility to make the front-engined T4.

The last T3s—including the desirable Limited Last Edition models—all came from Austria, regardless of whether they were two- or four-wheel drive. Production for the European market finally ended in 1992, but Volkswagen’s South African factory continued manufacturing the model until 2002.

Civilian Puch Panda 4×4 prototype (1991)

Steyr ended its collaboration with Fiat after briefly making the 126, the 500’s successor, from 1973 to 1975. The two companies kept close ties, and Fiat sought Steyr’s help to turn the Panda city car released in 1980 into a go-anywhere off-roader capable of taming the Alps. The Austrians, consequently, knew the Panda inside and out; and they identified potential the Italians either couldn’t see, or chose to ignore.

The once-popular beach car segment dominated by the Citroën Méhari and the Mini Moke was on the brink of extinction during the late 1980s. To rejuvenate it, Steyr took a Panda 4×4 and chopped off the roof after the B-pillar. Steyr also added roll bars, a plastic body kit, and a rear-mounted spare tire to give the Panda 4×4 a tougher look. The Austrians had created a Jeep Wrangler-esque off-roader scaled for Europe.

There were no mechanical modifications under the sheet metal. The 4×4 prototype came with a 1.1-liter four-cylinder engine that generated 55 horsepower. It wasn’t quick, but the four-wheel drive system easily made it one of the most capable off-roaders on the European market. Demand for beach cars must have been at an all-time low, because the production-ready prototype remained just that.

Military Puch Panda 4×4 prototype (1991)

As a contract manufacturer, Steyr fully understood the concept of economies of scale. That’s why it built a second open-top Fiat Panda 4×4-based prototype with the Italian Army in mind. The military-spec version was closely related to its civilian sibling, and the two shared many mechanical components, but Steyr added a fold-down windshield; more durable, metal bumpers; and fabric doors.

The timing was certainly right. Fiat stopped making the Campagnola, a Land Rover-like off-roader, in 1987. The older examples serving in the Italian Army’s fleet had started to retire, and there was nothing with local roots capable of replacing them. Placing an order for Steyr’s prototype would have at least kept Fiat in the equation, but Italian officials gradually replaced the Campagnola with the Land Rover Defender. Like the civilian prototype, the combat-ready model never reached production.

Treser Cabrio (1991)

In 1981 Walter Treser, a German engineer who worked on the original Audi Quattro, created the tuning company that bears his name. His first project was turning the Quattro into a convertible with a folding hardtop, a modification Audi never even considered making. The conversion was expensive, and the car was out of reach for many motorists, so Treser began chopping the top off the second-generation Volkswagen Polo in 1991 in a bid to reach a wider audience.

Volkswagen never envisioned the Polo as a convertible, so the conversion process was easier said than done. Steyr helped make it a reality. Volkswagen was so impressed by the final product that it agreed to sell Treser’s Polo though its official network. At the time, the second-generation Polo was getting seriously old, so executives hoped a hip, tuner-friendly model would help draw younger buyers into showrooms.

The regular Cabrio came with a 1.4-liter four-cylinder engine that generated 55 horsepower. Those who wanted performance on par with the car’s head-turning design could pay extra for a 75-horsepower, 1.6-liter four-cylinder sourced from the Polo GT.

Treser sold approximately 290 examples of the Cabrio between 1991 and 1993.

The rest

Austria-friendly 500s, combat-ready Panda offshoots, and rear-engined roadsters that never saw the light at the end of a production line are fascinating to unearth. However, the most interesting part of walking through the aisles of the Steyr museum is seeing the wide array of cars the company touched.

Steyr turned the second-generation Golf into the off-roading Golf Country; one of the roughly 6300 examples built lives in the museum. The Pinzgauer and the Haflinger are relatively well represented, and two-wheeler fans won’t be disappointed, either. There are hundreds of bicycles, mopeds, scooters, and motorcycles displayed in and above the museum. Some are in like-new condition, while others look like they were pulled out of a barn (probably because they were).

What’s with the Lincoln Blackwood? Magna-Steyr participated in the project, and the issues it encountered with the tonneau cover quietly forced Lincoln to delay the truck’s launch. And, is that a Pontiac Aztek in the next row? Yep—Steyr designed and manufactured the available all-wheel-drive system. The cars built in Graz through a partnership between Chrysler and Steyr are all part of the collection, too, including a third-generation Voyager minivan proudly wearing a “made in Austria” sticker on the tailgate.

BMW’s Hydrogen 7 prototype? Check, Steyr made the tanks. An all-wheel-drive second-generation Saab 9-3 convertible? Present! It was a one-off that decision makers at the Swedish brand didn’t want. Indeed, Magna-Steyr’s history is rich, weird, and fantastic. These days, the hodgepodge of manufacturers associated with the company lives on—the BMW-platformed 2020 Toyota Supra? Magna assembles that, too.