1927 Chevrolet found in Lake Huron shipwreck

Ken Merryman is on a seemingly endless search for Great Lakes sunken treasure. And by treasure, we don’t mean the kind that makes him wealthy. In fact, Merryman thinks the most valuable item found aboard the recently discovered wreckage of the steamship Manasoo—a 1927 Chevrolet coupe—should probably stay right where it is.

Merryman, a retired engineer who lives in Minnesota and has been scuba diving for 50 years, spends his summers looking for undiscovered shipwrecks. Although he calls searching for Great Lakes wrecks a hobby, it’s much more important than that. Merryman and his team—which for the Manasoo project included Cris Kohl, Jerry Eliason, Jared Daniel, and photographers Terry Irvine and Greg Hilliard—indeed enjoy the hunt, but their work helps fill in historical gaps and find answers for relatives who’ve lost loved ones to the unforgiving lakes.

“It takes a lot of time and effort, but it’s worth it,” says Merryman, who has helped locate 20 Great Lakes shipwrecks. “It’s a great feeling when you find what you’re looking for.”

Some of the team’s discoveries are more satisfying than others, of course. The Manasoo is one of them.

‘A dreadful night’

There’s a long-held superstition that changing the name of a ship is the kiss of death. Veteran mariners will tell you it’s a lot more than conjecture, it’s a reality—and the Manasoo’s fate certainly bears that out.

Built in Scotland in 1888, the ship spent 39 years as the Macassa, working on Lake Ontario carrying tourists and cargo between Toronto and Hamilton. Then in 1928, it was purchased by the Owen Sound Transportation Company and mainly used on Lake Huron to ferry passengers between Manitoulin Island and Sault Ste. Marie (also known as the Soo). The ship’s name was changed to reflect the two communities it served. It just didn’t serve them for long.

On September 14, 1928, the Manasoo departed Manitowaning, on Manitoulin Island, with an atypical passenger list: 17 crew, four (human) passengers, and 116 head of cattle. Butcher Donald Wallace and his partner had purchased the livestock and were bringing the cows home to southern Ontario. Wallace’s 1927 Chevrolet coupe was also aboard—ownership was later verified by researching the license plate through the Ontario DMV’s database.

“We don’t know much more about Mr. Wallace than that,” Merryman says, “other than he went to Manitoulin Island with $3000 in his pocket and returned with $50.”

The fact that Wallace returned at all certainly placed him in the minority. As night fell, the ship—with the cattle in cages on the upper deck—encountered high winds and rain that tossed the ship violently. Dr. Art Middlebro was a medical student at the time and served as the ship’s purser, and he recalled the ship’s horrifying final hours in a 1982 interview.

“The weather got very bad, with a strong southeast wind getting up to gale force,” Middlebro said. “It blew so hard (that) it blew chairs right off the deck, up over the rail, and overboard. I opened the door on the top deck and it blew it right off its hinges—blew in the gangway door—and we took a door off the dining room and spiked it up… to keep the water out.

“Some of the crew were terrified; some of them were very calm. As we got farther south… just off Griffith Island about a mile and a half, the boat listed to port into the wind and kept on slowly going over, and most of the crew, including myself, managed to clamor up along the rail. It was dark and miserable and rainy, you couldn’t see very much, although there was some sky glow. I realized the ship was going to sink, and as I saw the stern disappearing slowly, I ran down the side of the ship and dove in, and headed for Griffith Island light.”

In the early hours of September 15, 1928, the Manasoo disappeared beneath the icy waters of Lake Huron, about a mile and a half from Griffith Island in Georgian Bay. Faced with a nearly impossible swim to safety, Middlebro said he took “25 long strokes” before he noticed a dark patch in the water to his right. It was a life raft.

“I climbed up on it and helped the chief engineer up on it,” Middlebro recalled. “The captain, a passenger [Donald Wallace], and the oiler were already on it, and in a few minutes the mate came along—Ozzie Long—and I helped him up on the raft. This was about 2:30 in the morning.”

Two hours later, Middlebro recalled that another ship, the Manitoba, passed by about 200 yards away, but it was too dark and too far for the survivors to be seen.

“Shortly after that, the wind dropped and started from the southwest, blowing us out into the bay… towards the middle of the bay,” Middlebro continued. “We all felt the cold very much. I just had on a suit of Etchway button-less underwear, as I had to get up in a hurry. We were on this raft the rest of Friday night… until 4 o’clock Monday afternoon. Early on Monday the chief engineer died, and we had to push him overboard, as the raft was sinking in one corner. However, about 4 o’clock we saw the Manitoba and wildly flagged, and she came and put a boat out and brought us home. Out of 21 of us aboard, only five survived.

“It was a dreadful night. Terrible.”

The search for the Manasoo

Sources cannot agree on the number of ships lost in the Great Lakes, but the Great Lakes Shipwreck Museum puts the number at about 6000 (along with 30,000 lives lost). Of those, Cris Kohl’s research indicates that only 1500 have been discovered, which makes every find a big deal.

Merryman says the Manasoo is an even bigger discovery since it is one of only five wrecks with a wooden pilot house and one of just four that were found with a car aboard. It’s the only Great Lakes shipwreck that has both.

Issued an archeological license from the province of Ontario, the team began the search with less-than-definitive information about where the Manasoo actually went down. And after a 30-square-mile search spanning two summers, the ship still hadn’t been located. Frustrated but hopeful, the team received a tip from a retired local diver, who said the ship was closer to the Griffith Island lighthouse in shallower water. That made sense to Kohl, who thought it logical that the captain of a sinking ship would head directly for the lighthouse. Merryman agreed and the search resumed.

On June 30, the team discovered the Manasoo in 200 feet of water—50 feet deeper than the retired diver had suggested but a far cry from the original search-area depth of 250–400 feet. Merryman sent down a tethered camera to take a look, and that’s when the team excitedly discovered the wooden pilot house… and the car… and something else that Merryman says he’d never seen: the ship’s clock, intact.

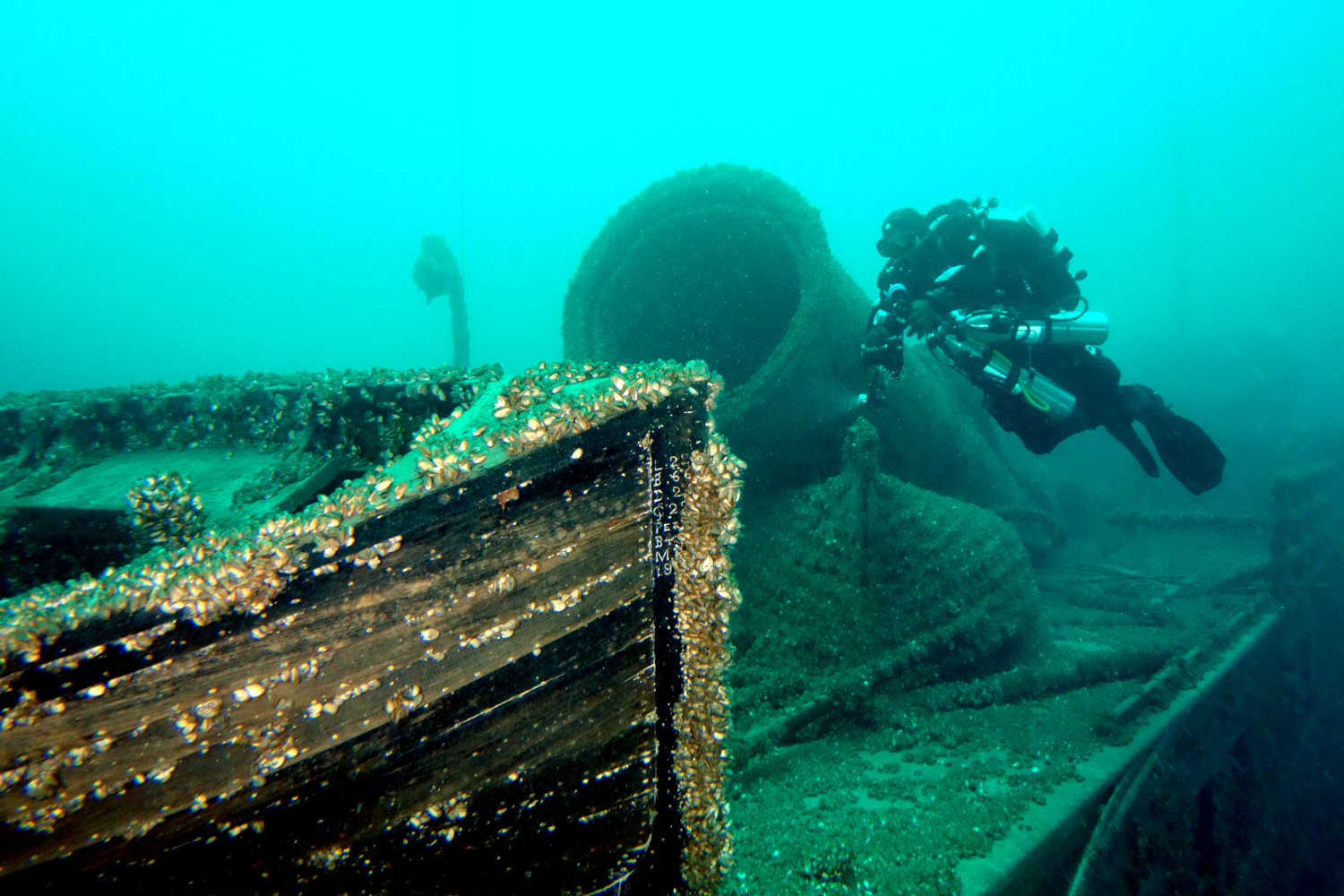

The team returned to the ship on July 9, and Merryman, Hilliard, and Irvine took the plunge. Merryman recorded video of the ship—getting a good look at the ’27 Chevrolet through the side openings—while Hilliard and Irvine, Canadian technical divers, took photographs.

Frustration? Nope, satisfaction

In the weeks that followed, Kohl continued to research the vessel. He eventually learned that the ship had actually been located only three weeks after it sank, and the newspaper account of the discovery included a more accurate location of the ship’s whereabouts—information that would have come in quite handy had it been found earlier. Regardless, no one was complaining.

“Historically speaking, shipwrecks from the 1800s are much more significant, but the Manasoo is one of the neater wrecks I’ve been involved in,” Merryman says. “You don’t see many cars, obviously, so that was a real treat.”

Merryman says some have suggested that the car be raised and placed in a museum, but he says that idea is neither cheap nor simple. “The car looks great just as it is, but you have to consider that metal rusts and gets thinner over time, and it’s been down there for 90 years. Thankfully, divers aren’t allowed to touch it since it’s a protected site. And raising it would not only be expensive, it could cause irreparable damage to the car. I just don’t think raising it is practical.”

Merryman and his team will continue to search the Great Lakes next summer. Up first are a pair of ships that went down near Hamilton, Ontario, during the War of 1812. Don’t expect them to find any cars in those. But who knows what they might discover in other post-1900 wrecks. We’ll let you know.